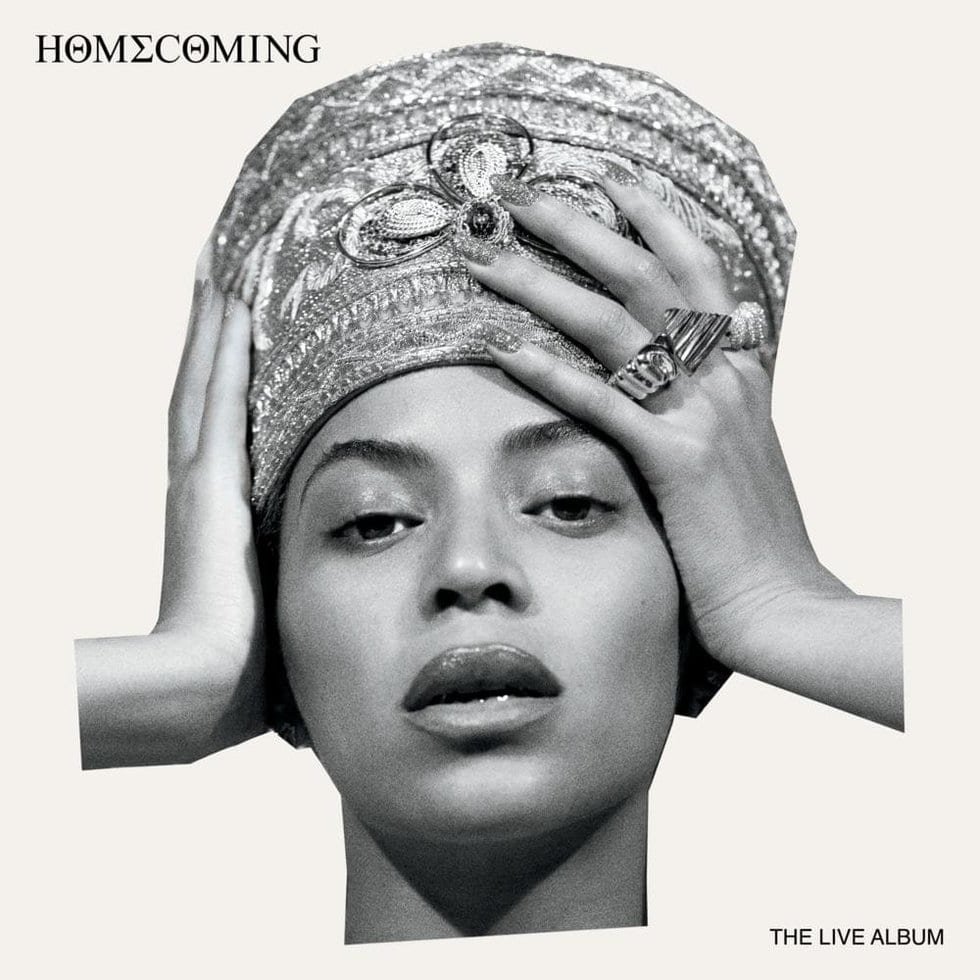

When Beyoncé postponed her Coachella set by a year after becoming pregnant with twins, she shed the need to promote an album (2016’s Lemonade) and could focus on putting on a show. Her two sets at 2018’s Coachella felt like work as consequential as Lemonade or her earth-shattering 2013 self-titled album. The setlist wasn’t a parade of hits as much as a recasting of her catalog: in paying tribute to America’s historically black colleges, she re-calibrated her music to incorporate marching-band instrumentation while keeping the most Pavlovian cues (the siren-bark that signals “Formation”) intact.

But for all the great songs involved, the show wasn’t as exhilarating to watch for the music as for its scale: hundreds of people onstage, Beyoncé surveying the crowd from a giant crane, superhuman dancing, fireworks we barely even notice at that point. Watching the just-released Netflix concert film Homecoming and listening to its accompanying live album imparts some of the same thrill as watching some of those old Soviet films where they leveled whole hills to make the sets and spent as much government money as they could on extras. It might be the best show-as-statement in pop history, putting as much (if not more) ambition into its two-time run as any of her blockbuster albums.

The film also clocks in at well over two hours and intercuts the performance with arty faux-home-video footage of behind-the-scenes rehearsals and Beyoncé cooing over her babies. The film makes the singer’s intentions strenuously clear: “I will never push myself that far again,” she half-laughs at one point. How to balance raising twins with the demands of putting on one of the biggest concert productions of all time, especially after such a difficult pregnancy? The film doesn’t say, which makes sense, as Beyoncé directed the film, and no way would she show herself handing her kids off to nannies.

She shows herself mostly smiling in long-shot, heading rehearsals, and gives no impression that she was anything other than a sweetheart while running her small army. Not to say she wasn’t, but we wouldn’t know. The singer’s reclusiveness and refusal to grant interviews make it clear that no word from the Carter estate slips through the gate until it’s filtered through the mesh of her regal, #flawless image. (Even the name “Beychella” was coined at Beychella, with a disembodied DJ Khaled explaining precisely how to pronounce it: “BEY-CHELLA,” he asserts, followed by three airhorns announcing the birth of a meme.)

As great as it is to have a star as ambitious as Beyoncé in the upper echelons of pop culture, the top-of-the-world thing is getting a little irritating. It’s harder to defend the crass meanness of “Bow Down” when the Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie TED talk on feminism is sequenced halfway across the concert set. I always thought of the Adichie speech as an ironic counterpoint to Beyoncé screaming “bow down bitches”, but now I know they’re separable on her whim. If you heard the album before the film, you’d think she was directing “suck my balls” at the crowd (she’s simulating a frat initiation), and at that point, we wouldn’t put it past her.

I’d never heard her verse on DJ Khaled’s “Top Off” before Homecoming, but it affirms my fears that her brags are losing their nuance beyond “I’m rich, and you’re not.” “If they wanna party with the queen they gotta sign a non-disclosure,” she barks. At least she didn’t do the Carters track “Nice”, on which she boasts about not putting Lemonade on Spotify before chanting “fuck you”. We already know how famous she is, and it’s not interesting to hear her talk about it when her lyrics aren’t escapist or at least clever.

God knows Homecoming is impressive on its own without needing to tell us how impressive it is. It’s a huge risk, not only in terms of the scale of the production but the fact that it offers nothing like a linear greatest hits. Some of the songs are performed for only a few seconds (we hear Drake’s “good girl” chant from “Mine” but none of the exquisite piano balladry that defines the song). Others are recast, often daringly, in marching-band format. “Crazy in Love” sounds a little weirder thanks to an insistent whistle that shrieks along with the main riff, and Lemonade‘s Betty Davis-ish “Don’t Hurt Yourself” sounds even more like a war anthem. That they’re all blurred together by instrumental interludes where the marching band’s going wild and hyping everyone up gives it something in common with an old-style soul revue, and the elbow grease we see onstage mitigates the common complaint with pop shows that it’s less interesting to see someone do karaoke with dancers than musicians actually exerting themselves on their instruments.

Long segments don’t even feature Beyoncé, which can be trying on the album but in the film are understood as the accompaniment to dance routines and skits. It’s amazing how often she disappears into the scenery in the film, a guiding light among the masses rather than a center of gravity. She cedes a lot of space to the dancers, though the show could have benefitted from more guests (she and J Balvin missed each other by a year). Absent once again is New Orleans bounce queen Big Freedia, whose “Formation” lines are lip-synched by Beyoncé. Freedia’s disembodied voice is still sadly better-known than her bold, gender-fluid image, though then again, Bey does introduce the show with “ladies and gentlemen…”

The show wraps up with an astonishing version of “Love on Top”, which pretty much skips straight to that part, before the credits roll. After all the sights and sounds we are treated to throughout Homecoming, the credits on their own are mind-boggling in the sheer number of names we see flash across the screen. They’re soundtracked, by the way, by the only new piece of studio music to comprise a part of this project: a cover of Maze and Frankie Beverly’s “Before I Let Go”, embellished with an extra rap verse. “I pull up to Coachella / In boots with the goose feathers / I brought the squad with me / Black on black bandanas,” she explains, giving us a behind-the-scenes for her own show in the lyrics of her own song. Who else would put on a two-times-only, two-plus-hour, two hundred-plus-person show celebrating the history of black colleges, the history of black American music, and the history of her own career—and then write a verse bragging about pulling up to it?