We can hope that one day American schools will feature mandatory courses on racism. If we can teach history by region (European, World, American) surely we can also do so by theme. A course on American racism would help to complement existing courses on ethics and civics, for what is the point of those studies if not to teach the practical application of their subject? If America is ever to acknowledge and rise above the virulent racism that currently holds it in thrall, it will come from teaching history and empathy to younger generations in the hopes they may avoid at least some of the depravity and vice of their parents’ world.

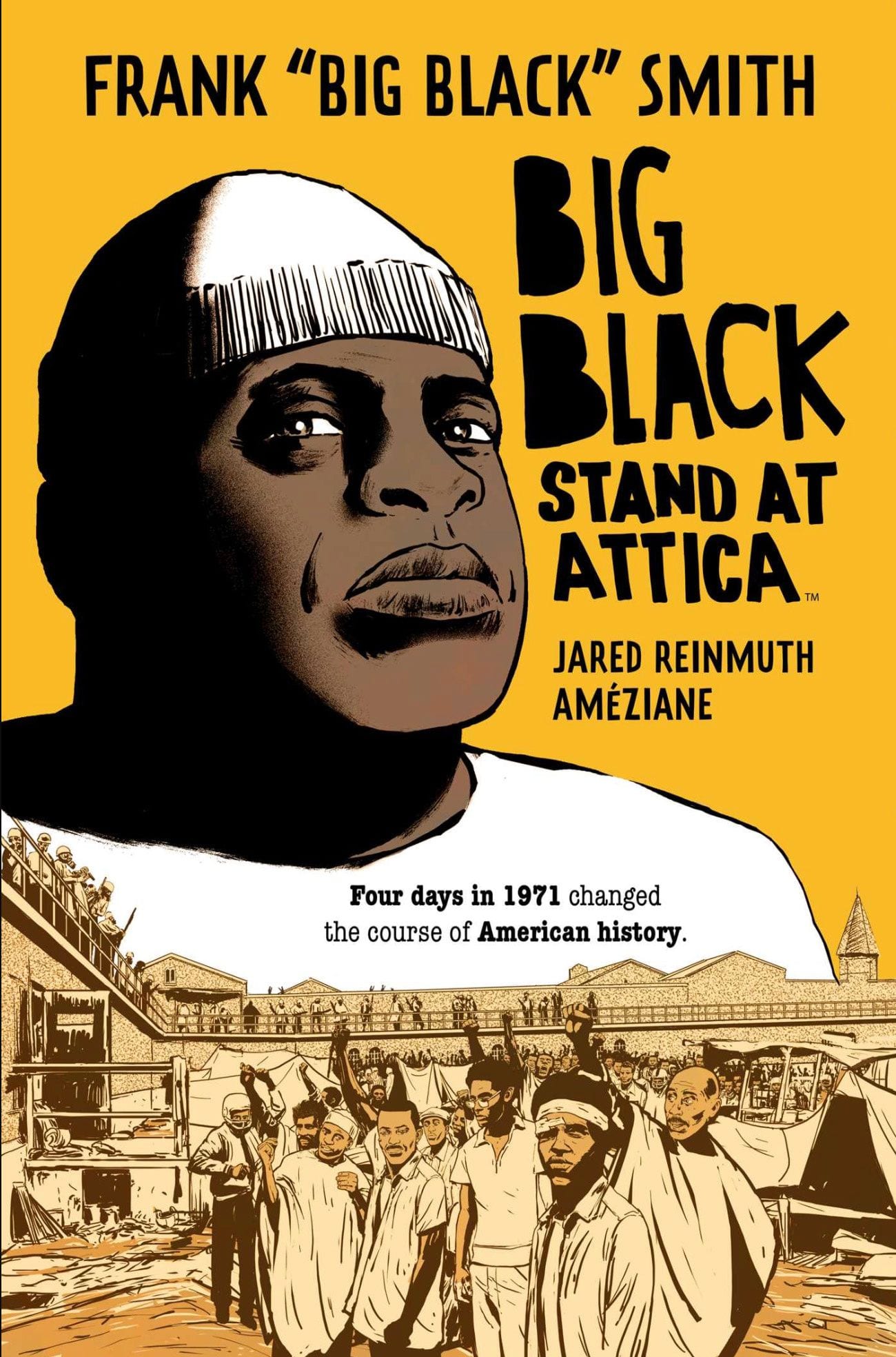

In this more enlightened future, one of the topics our American Racism course will cover is the Attica Prison Riot of 1971. Half a century past, the Attica Prison Riot of 1971 offers a tragic and yet stirring example of both the viciousness of white supremacist hate (and its virulent grip on US law enforcement) as well as the dignity, strength and resistance of imprisoned African-Americans. As we approach the 50th anniversary of this courageous and tragic event (9-13 September), efforts to preserve its memory have taken a variety of forms, most recently the beautiful and harrowing graphic novel Big Black: Stand at Attica.

The details of the revolt and its aftermath are now well documented, despite the efforts of white US officials to bury and confuse them after the fact. The revolt at New York State’s Attica Correctional Facility (a maximum-security prison opened in 1931 that is still in operation) took place in the context of a wave of prison protests that swept the country in the early ’70s. Prisoners and supporters sought to draw attention to the brutal and inhumane conditions of American jails, which then as now were filled with disproportionate numbers of African Americans.

Nation of Islam and other civil rights groups were organizing among inmates, and a self-organized group of inmates at Attica had already submitted a manifesto to the prison authorities. They demanded an end to slave labour, respect for inmates’ civil rights, and a stop to the brutalizing treatment from guards. Authorities reacted strongly, hunting down signatories and punishing them with solitary confinement and other punitive measures. This only increased inmate solidarity, which they expressed in fasting as well as makeshift armband protests.

The ‘revolt’ itself began on 9 September 1971. Harsh crackdowns by the prison guards, coupled with rumours of beatings and murder that were given added fuel when a prisoner was murdered by guards in California, led a group of prisoners at Attica to fear they were being set up for a possibly fatal ambush when a guard accidentally locked them in a corridor. Fearing for their lives, they overpowered the guard and broke out of the corridor. When other prisoners saw this, they leapt into action, spontaneously overpowering guards throughout the facility. Soon the entire prison was in inmates’ hands and 42 correctional officers and civilian workers had been taken hostage.

The inmates initially thought they were fighting for their lives, but once they were in charge of the prison, their concern became one of retaliation by the white correctional officers. A team of prisoners quickly organized a security squad, led by Frank “Big Black” Smith, to protect the hostages; they also formed a negotiation team and other administrative units. A list of demands, similar to the earlier manifesto, was drawn up, with the additional demand of amnesty for prisoners who took part in the occupation.

Robot by Thor_Deichmann (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

The prisoners spoke eloquently of their situation to reporters who visited the jail, and for four days negotiations dragged out, covered on national television and monitored by teams of civilian observers to ensure the safety of both sides. During this time, Smith recounts poignantly, inmates exulted in being able to sleep outside under the stars for the first time in many years.

The attempt to negotiate was only in good faith on the part of the inmates; correctional officers, with the approval of New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and US President Richard Nixon, launched an all-out attack on the prison on 13 September. Helicopters bombarded the prison with tear gas, after which officers opened fire with shotguns and stormed the gates.

What ensued was a massacre. Correctional officers’ ranks had been bolstered by volunteer police officers and local white supremacists, many of them armed with explosive ammunition and other weapons banned by the Geneva Conventions. They deliberately shot to kill, and proceeded to torture and murder prisoners who surrendered. Nor did they distinguish between prisoners and hostages. Authorities had already accepted that the hostages would likely be killed during the attack, and would blame inmates for their murders. By the time the dust settled, 128 inmates had been shot, and 29 prisoners and 9 hostages had been killed.

Larry Getlin describes the scene in a retrospective article in the New York Post:

“What followed were acts of brutality so heinous they beggar the imagination. Officers were shooting indiscriminately, smashing in convicts’ heads with the butts of their guns and shooting them, then sticking gun barrels in their mouths for laughs. One prisoner was shot seven times, then handed a knife by a trooper and ordered to stab a fellow prisoner. (He refused, and the officer moved on.) Another was shot in the abdomen and leg, then ordered to walk. When he couldn’t, he was shot in the head.

“Some of the black prisoners heard the N-word screamed at them as they were shot, or taunts of, “White power!”

…

“Naked prisoners were forced to run gauntlets, beaten with batons as they ran. One 21-year-old inmate shot four times heard troopers debating “whether to kill him or let him bleed to death … as they discussed this the troopers had fun jamming their rifle butts into his injuries and dumping lime on his face and injured legs until he fell unconscious.” Prisoners were made to crawl naked on concrete through blood and broken glass, subjected to Russian roulette and even forced to drink officers’ urine.

“For the victims of this abuse, no medical care was made available, in some cases for days or even weeks. One doctor was ordered not to treat a shooting victim with blood running down his face, and a guardsman was literally ordered to rub salt in another prisoner’s wounds.”

Smith, the narrator of Big Black: Stand at Attica, was one of those tortured. Ironically, the officers’ desire to torture him for revenge might have saved his life, while other organizers were being deliberately gunned down in cold blood.

Although the police cover-up of what actually happened carried the day in national media – the carnage and deaths were falsely blamed on the inmates themselves – the truth eventually emerged. Activists, lawyers, investigative journalists, prisoners and their families all worked assiduously in the years that followed to bring forward the truth.

As word began to emerge of what had really happened, they organized protests and rallies. Lawsuits were filed against the State of New York for civil rights violations, and finally in the year 2000 – after nearly 30 years of struggle – the State settled with the former inmates (who in 1976 had been pardoned for their role in the occupation) for $8 million. (A separate $12 million settlement was made with families of the prison guard hostages who were murdered by their fellow officers during the attack).

Big Black Stand: at Attica does a marvellous and respectful job of telling this harrowing story. It takes the perspective of Frank “Big Black” Smith, who headed up the improvised inmate security team during the occupation and played a key role in protecting the hostages. Following his release, he overcame his drug addiction and became a substance abuse counsellor; he later studied to be a paralegal and worked as a legal investigator for defense lawyers. He also became a tireless activist for prison reform.

The book chronicles Smith’s life from childhood, the son of a poor single mother and former sharecropper whose parents had been slaves. Sentenced to 15 years in a maximum-security prison for robbery (a disproportionate sentence for a first offense), he was well-liked by his fellow inmates, for whom he also served as football coach (he’d excelled at the sport in high school). Although he wasn’t one of the instigators of the riot, he was approached by its leaders to take on the security chief role, since they figured inmates would listen to him and stay in line (both because of his level-headedness, as well as his massive physique). This made him a sought-after target for retaliation by the police and prison guards who carried out the slaughter.

The occupation and its horrific, brutal aftermath occupies the bulk of Big Black Stand. The violence is harrowing. It would be easy to lose oneself in despair as the outcome – already known to the reader – unfolds, but the authors work hard to ensure the carnage is complemented by the strength and dignity of the inmates, who repeatedly and courageously refuse to concede to their oppressors.

A special spotlight is also shone on the role played by Rockefeller and Nixon in the crisis. The authors make the two men’s complicity in the violent and murderous outcome vividly apparent. Rockefeller in particular, an aspirant for the White House, is more worried about the occupation’s impact on his campaign than the lives and safety of either inmates or hostages. Right up until the end, prisoners and their supporters hoped for the Governor’s personal intercession in the crisis (when the helicopter appeared to commence the attack, prisoners initially believed it was the Governor coming to negotiate). Yet Rockefeller refused to intervene, and ordered the assault on the prison with full knowledge it would cost the lives of inmates and hostages alike.

He was later revealed to have shrugged off the deaths of hostages at the hands of their uncontrollable fellow guards in a phone call with President Nixon, brushing off their murders with the comment, “That’s life.” The book does an excellent job of underscoring Rockefeller’s guilt, and takes particular relish in chronicling how the ensuing scandal dogged him for the rest of his days.

The book also dishes out scathing and deserved criticism to journalists covering the tragedy. They accepted at face value the story they were given by police, blaming the murders on inmates and even running the false rumour that hostages had been castrated, despite having no evidence whatsoever for either claim. The tendency of otherwise astute white reporters to swallow and regurgitate intact the claims of white police officers is one of the prevailing shames of modern journalism. It’s only in the present moment that — thanks to the work of Black Lives Matter organizers — some journalists are starting to realize the scale of police dishonesty when it comes to racist violence enacted by the authorities. (See also: “‘The View from Somewhere‘ Exposes the Dangerous Myth of ‘Objective’ Reporting”.)

The authors spare no efforts to remind readers of this problem. In one panel, a guard shows off the dead bodies to reporters. “This one came at me with a knife. Barely got a shot off in time,” he lies.

“The idiot reporters don’t even realize that man was shot in the back,” rages a nearby doctor to his colleague. “Damned lies and a coverup,” responds the other. In reality, several of the medical responders were complicit in the racist violence, refusing to treat injured inmates.

While the story itself would suffice for a superb graphic novel, the artwork by French artist

Ameziane deserves special notice. Each panel is a work of art in its own right; the detailing is remarkable. The book’s setting is mostly uniform and grim – a bleak prison of brick and steel. But Ameziane’s detail is absorbing. Take, for example, a two-page panel depicting a visit to the occupied prison by Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther Party (and one of the observers who tried to help facilitate negotiations).

Seale speaks to the inmates, who are massed in the courtyard and perched on window ledges. Immensely detailed brickwork merges with intricately interlaced bars on the windows. The inmates are garbed in a myriad array of found items, for once able to express their personal style: some have on football helmets and makeshift armour; others opt for the flowing robes and Muslim headscarves of Nation of Islam. Seale and the prison warden go head to head in gorgeously expressive juxtaposition: the warden’s racist disdain and worried grimace belie his effort to seem stern and threatening; Seale’s gaze burns with a combination of passion and resignation, the firm set of his mouth expressing his own worry for the inmates’ safety.

Ameziane’s illustrations are versatile, too. Most of the comic art is realist in style, but occasional large vistas are depicted in abstract sketch format. The prison assault itself is depicted in variegated form over several pages: full two-page graphically realistic action spreads alternate with cartoon violence (a good way of ensuring the book doesn’t risk losing itself in lurid voyeurism). The lush, full-colour spreads that appear throughout are mesmerizing. Indeed, if the narrative wasn’t so horrific and fast-paced, forcing the riveted reader to flip pages rapidly, one could spend a significant amount of time simply appreciating the detail and style of each panel.

The book is the third of Ameziane’s ‘Soul Trilogy’, which also includes

Muhammad Ali (2016, Dark Horse Books) and the Angela Davis biopic Miss Davis (2020, Éditions du Rocher, not yet available in English), both written by Sybille Titeux. Ameziane has also worked with the remarkable Mexican writer Paco Ignacio Taibo II to produce comic adaptations of his work.

Big Black: Stand at Attica was written by Jared Reinmuth, whose stepfather, Daniel Meyers, led the Attica Brothers Legal Team in the 26-year legal battle for justice. Smith, described by his co-author as “a wonderful storyteller”, became friends with the family. He shared his story with Reinmuth in the late ’90s; the aspiring writer, actor and director initially thought it could provide the basis for a screenplay. Following Smith’s death in 2004, Reinmuth continued working with his widow, Pearle Battle Smith, to chronicle Big Black’s story, which has finally emerged in graphic novel format. The book also features a moving introduction by Meyers.

Big Black: Stand at Attica is a superb graphic novel, excelling well beyond the standard fare of the now ubiquitous bio-pic. Written by contributors with personal ties to the events, the story it tells is one which is vitally important to remember. The narrative, illustrated with Ameziane’s lush and magical artwork, is a stirring tribute to the strength and courage of those who died, and a powerful call to action in the ongoing battle against the systemic curse of white American racism.

* * *

Additional Works Cited:

Clines, Francis X. “Postscripts to the Attica Story“. The New York Times. 18 September 2011.

Getlin, Larry. “

The True Story of the Attica Prison Riot“. The New York Post. 20 August 2016.

Rollmann, Hans. “‘

The View From Somewhere‘ Exposes the Dangerous Myth of ‘Objective’ Reporting”. PopMatters. 18 October 2019.

- BIG BLACK: STAND AT ATTICA First Look

- Big Black Stand At Attica (9781684154791): Smith ... - Amazon.com

- Mona Ameziane (@mona.ameziane) • Instagram photos and videos

- Djamel Ameziane - Wikipedia

- Ameziane v. Obama / Ameziane v. United States | Center for ...

- Amazing Améziane - Europe Comics

- Jared Reinmuth | Facebook

- Jared Reinmuth | Official Publisher Page | Simon & Schuster

- The True Story of Four Days That Changed The Course of History in ...

- Interview with Frank Smith (Big Black)

- Frank “Big Black” Smith: 1933-2004 | Democracy Now!

- Attica Prison riot - Wikipedia

- Frank Smith, 71, Is Dead; Sought Justice After Attica - The New York ...