Life is similar to narrative in that both have a beginning, middle, and end. Death gives a completed shape to a life in the same way that a story’s ending gives a completed shape to a narrative. Once completed, the contours of a story—all the twists and turns, ups and downs — become apparent, and each moment takes on a particular significance in relation to the narrative whole. Perhaps this is why our 21st century western society, which is so bad at dealing with and discussing death, is so devoted to consuming narratives in all aspects of our lives.

But what happens to narrative without form, story without definite shape? The latest installment of the techno-dystopic Netflix series Black Mirror, Bandersnatch (2018), which aired late-December, considers this question. The movie’s choose-your-own-adventure interactive format, with multiple “paths” leading to multiple endings, reflects the dark underbelly of our current habits of narrative consumption and provides an uncomfortable glimpse into a world in which narratives no longer have form.

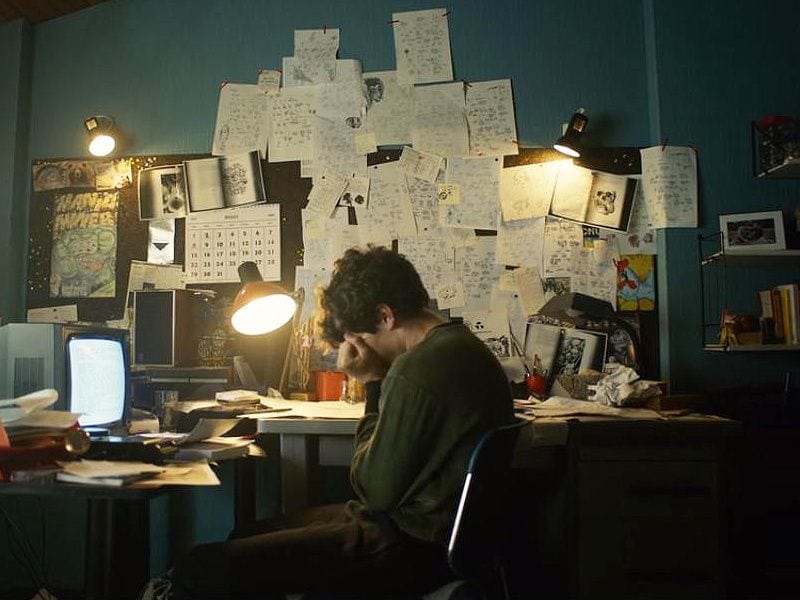

Written by Charlie Brooker and directed by David Slade, Bandersnatch is the story of Stephan Butler (Fionn Whitehead), a young video game programmer in the mid-’80s, who creates an interactive video game modeled on a “choose your own adventure” novel. Like the novel’s author, who went insane and murdered his wife, Stephan slowly becomes convinced that his decisions are being controlled by an external force, which leads him down a variety of dark “paths”.

The experimental and controversial component to Bandersnatch is its interactive format. At various points throughout the movie, a black bar appears at the bottom of the screen and prompts the viewer to choose between (usually) two options to determine what Stephan does next. The choices range in significance from what type of cereal Stephan has for breakfast to whether he should bury or chop up his murdered father’s body. There are six major paths to follow, the majority of which have more than one ending variation. True to Black Mirror‘s nature, none of the paths lead to good options. Stephan ends up either making a terrible game, or going insane, or murdering other characters and going to prison, or discovering he’s part of a government mind control experiment, or dying as a child in a train accident with his mother, or some combination of these unpleasant outcomes.

Bandersnatch‘s interactive design is modeled on the Choose Your Own Adventure (CYOA) children’s book series developed by Edward Packard in the early ’70s (the first book was published by Vermont Crossroads Press in 1976). The second-person point-of-view novel allows the reader to choose how the story continues by turning to a designated page somewhere else in the book. Bandersnatch is causing Netflix some legal trouble, though, as Chooseco, the current owner of the Choose Your Own Adventure trademark, is suing the streaming platform for trademark infringement. The legal turbulence surrounds the actual use of the CYOA phrase in Bandersnatch, not the interactive design in itself.

In fact, Bandersnatch‘s interactive format is one of several recent experiments in interactive television, such as Steven Soderbergh’s Mosaic (2017-18), aired on HBO, which allows the viewer to choose from a variety of perspectives through which to view the unfolding murder mystery, though the plot itself is not alterable (see Jackson Arn’s “Soderbergh’s ‘Mosaic’: The Future of TV?“). But Bandersnatch deviates from these precursors in two important ways: unlike the CYOA novels, the movie is told from the third-person point-of-view, and unlike Mosaic, Bandersnatch allows the viewer to alter how the plot unfolds.

Unlike the CYOA books, the protagonist in Bandersnatch is not the audience. The third-person POV positions the viewer as the puppet master who makes the puppet dance to a tune that includes murder, suicide, drugs, and mental breakdowns, with a reckless disregard for the fact that Stephan makes it increasingly clear that he doesn’t want to dance anymore. This voyeurism invites a borderline sadistic relationship between the viewer and Stephan. But the ability to affect the storyline is the major experimental aspect of the movie. The interactive format offers a seeming creative freedom to its viewers. When all of the options are interesting and well written as they are in Bandersnatch, who wouldn’t enjoy the opportunity to choose what the protagonist does next? But the freedom, of course, is only a seeming freedom. The viewer can only ever choose between pre-programed, pre-scripted options.

That Bandersnatch invites this illusion of creation on the part of the viewer is evident by the video game review that appears at the end of most “paths”. Just before the credits role, an onscreen reviewer gives his assessment of the game. For example, the game’s production might be subpar because it’s rushed to completion, or the game’s release might be marred by the crimes committed by its creator, or the game might be boring because its creator was “on autopilot” due to his prescription medication habit. But each choice made by the viewer throughout the movie affects the way Stephan builds his video game, so the reviewer is really critiquing the Netflix viewer’s narrative, rather than Stephan’s game. Bandersnatch the movie critiques the viewer’s creative choices, despite the fact that the choices are predetermined: it’s the joy of content creation without true creative freedom but with the full reality of scathing external criticism. Even the voyeuristic distance between the viewer and the consequences is an illusion.

Bandersnatch‘s main themes are heavy-handed: it’s an interactive movie about the creation of an interactive video game whose programmer openly meditates on the tension between free will and determinism. The viewer is given the illusion of choice in a narrative about the illusion of choice. The secondary theme is a commentary on the relationship between death and narrative. Like death in a video game, death in Bandersnatch is low-stakes because the viewer returns to a “check point” in which she or he can choose a different option, next time through. For example, in the midst of an LSD trip, Colin (Will Poulter), another video game programmer, throws himself off his balcony, leaving Stephan with a parting “I’ll see you around,” claiming that death is meaningless because one just reenters the narrative again at a different point. His evidence? Pac-Man. When Pac-Man “dies” in the video game, he reenters the screen at a different point and starts again. And Colin, like Pac-Man, does return, rejoining the narrative on a different path. “I told you I’d see you around.”

But there’s more here than just the overt themes. Bandersnatch is a story without form. Because of the variety of storyline options, the form—the defining boundaries which give shape to the narrative—remains just out of the viewer’s mental grasp, retreating down another of Stephan’s “paths”. With so many available choices, one feels as if she or he doesn’t quite “get” the movie without having taken a peak at all of the paths. Twentieth-century narrative theorist Walter Benjamin, in his essay “The Storyteller” (1936), laments the way experience is no longer communicable through modern narrative forms. He associates this phenomenon with the shift from an oral-based narrative tradition to one dominated by the novel, which, for Benjamin, is a solitary and isolated narrative experience (compare sitting around the dinner table listening to someone tell a story about her or his day to sitting alone on your couch, wrapped in a blanket, engrossed in a novel). While this claim about the novel is debatable (and it very much is), the relationship between form, isolation, and experience is amplified in Bandersnatch.

Because of the variety of narrative choices, the combinations of which seem vast, each viewer experiences her or his own version of Bandersnatch, the form of which the viewer in charge of the remote creates. What happens to the shared experience, the collective wisdom (to use Benjamin’s language), that narrative can communicate in a story that can change with every viewing and is unique (or seemingly so) for every viewer? Without a set form, there can be no water-cooler talk about Bandersnatch, no collective reflection and analysis, because each viewer watched a different movie. Without a clearly defined beginning, middle, and end, the narrative form is lost, and without form, the narrative no longer connects its audience together or to a wider social world.

In the age of multiple streaming platforms, all of which offer a variety of worthwhile viewing options, what we choose to consume becomes more idiosyncratic, and more important. The collective nature of narrative consumption is lost as we all follow our streaming options down our own isolated viewing paths. This is ultimately what Bandersnatch‘s interactive format reveals. The techno-dystopian reality is not Stephan’s powerlessness as he becomes part of the game he created, but our own 21st century isolation. The image reflected in the black mirror of our powered-down TV screen is not of Stephan but of us, alone on the couch.