Sam Wagstaff was born in 1921 to a Polish mother and a semi-aristocratic father, growing up amid the trappings of East Coast American wealth. Raised in a fog of affluence and privilege, he eventually joined the Navy – the military outfit of choice for most elite northeasterners – fighting the Germans in World War II. Following the war, he returned to the US and drifted about for a few years before entering the heady world of advertising in the age of the hidden persuaders.

However, detesting the drunken, cynical world of three-martini-lunches and skirt-chasing ad-men, he turned his mind to art, and never looked back. Indeed, by the late ’60s, Wagstaff had become an unavoidable fixture on the New York art scene. He had money, famous charm, movie star looks, and an ability to identify the cutting edge even before it made its first incision. A tastemaker for the age, he was instrumental in the rise of a variety of major figures, setting up installations, shows, and parties designed to expose underground artists to the moneyed classes of post-’60s New York.

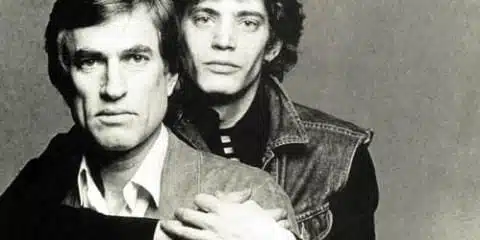

Certainly his most famous “discovery” was a young, radical photographer named Robert Mapplethorpe. Although separated by some 25 years in age, the two would begin a passionate affair that was part working partnership, part sugar daddy and boy toy, and part desperate romance. Mapplethorpe, who would rise to prominence as l’enfant terrible of the New York art scene in the ’70s and ’80s, was in many ways the opposite of his sponsor, lover, and champion.

Raised in a dreary working class suburb, he spent the ’60s drifting around the Max’s Kansas City crowd, broke, and hungry for a chance to find his voice. Mapplethorpe found in Wagstaff’s patronage a chance to establish himself, to achieve the attention he had always yearned for. And Wagstaff found in Mapplethorpe a young, sexy, protegé; but this 50-year-old man also found in his lover an entrée into the post-Stonewall underground gay scene then flourishing in the meatpacking district.

As the pair grew in fame and stature through the ’70s, they attracted no small amount of controversy – Mapplethorpe was repeatedly denounced for the S&M themes in his increasingly graphic photographs, Wagstaff for his ostentatious spending on 19th century images for his growing collections – but they also attracted the respect of young artists looking for influences. Indeed, these two men were, at the height of their fame in the early ’80s, among the most influential of figures in the post-Warhol art scene.

James Crump’s intriguing documentary seeks to restore Wagstaff – an enigmatic, enthralling figure by any reckoning – to his rightful place at the centre of New York’s art world in the ’70s and ’80s. Through interviews with his friends, colleagues, and critics, Crump develops a sense of both his character and his motivations. However, the film is oddly unwilling to play at straight biography, working more comfortably in impressions and whispers. In effect, Wagstaff grows out of a mere shadow at the outset of the film into a deeply textured shadow at the end.

Mapplethorpe, more strikingly, remains almost an unknown quantity. Perhaps this was a conscious decision on the part of Crump, so as to focus the discussion here on his less-famous lover, but the result is a somewhat lopsided view of their relationship, a fascinating man and his famous, but strangely ill-defined lover. Both men died of AIDS in the late ’80s, a fate which befell so many bright lights in the boho art scene. Thus neither has much opportunity to speak for himself here – we see a few clips from television spots and on-camera interviews, but none is terribly revealing.

But all of this vagueness appears to have a point. This is, ultimately, an artful documentary, and cleverly constructed. Beginning with a quotation from Walter Benjamin which explores the relationship between collecting and owning, entering and becoming, we see that Crump is working toward an understanding of Wagstaff as a combination of voyeur and collaborator; an explorer in forbidden territory. He was a collector – of art, of experience, of sex, of danger – but he was also, in every way, involved in these activities.

He collected his own life, then; through fragments, pieces of art, installation and anthologies, he told the world the story of himself. His collections, the film suggests, are the man. It’s a cerebral and complicated way to present a human being – as a heap of broken images, say – but it works on a certain level, given the overall lack of definition Wagstaff is given otherwise in the film.

His friends – Dominick Dunne, Patti Smith especially – seem unable to put their finger on just who he was. They tell stories, anecdotes, give suggestions about his nature, but he remains unformed, shadowy, even as his mystique deepens. Curiously, one leaves the film with a feeling both unsatisfied and quietly thrilled. A figure in black, white, and gray, indeed.