The summer of 2018 has produced some of the most challenging American films on the subject of race. Boots Riley’s inspired satire, Sorry to Bother You, tackles white privilege at an evil telemarketing firm (is there really any other kind of telemarketing firm?) while Carlos López Estrada’s Blindspotting wades through the muddled fallout of gentrification in Oakland, California. Finally, Spike Lee, who got this party started with 1989’s Do the Right Thing, wades into the conversation with his deeply flawed but wildly entertaining BlacKkKlansman.

Lee’s prescient frustration with gentrification in Do the Right Thing has inspired and influenced countless films, including the aforementioned Blindspotting. BlacKkKlansman rips the scab off ancient hatreds by comparing an early ’70s-era America still struggling to meet edicts of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to a 2018 America still grappling with its racism, with its economic inequality — and now Trump. Aside from snazzier phones and smaller shirt collars, little has changed in America in the past 40 years.

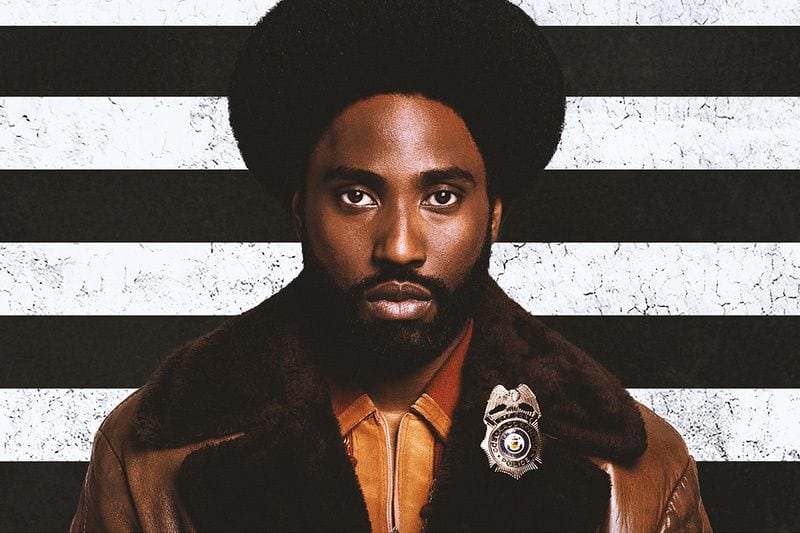

BlacKkKlansman is easily among the most entertaining films that Lee has produced in nearly two decades. Much of that is attributed to the stranger-than-fiction story upon which it’s based. In 1972, Ron Stallworth (John David Washington) became the first black policeman on the lily-white Colorado Springs police squad. Described by his bosses as the “Jackie Robinson” of law enforcement, Stallworth famously infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan by pretending to be a white man over the telephone. He would later chronicle his unlikely experience in the book Black Klansman (2014). Lee’s reverence for this book is clear, as he preserves most of the major plot points directly from Stallworth’s account. Indeed, Lee clings too tightly to his source material, as a few more liberties taken with the facts might have resulted in a deeper social message.

Perhaps the most interesting element of BlacKkKlansman is that Stallworth isn’t trying to make a political statement; he’s just trying to be a good cop. His passion for the profession and the impediment it poses to his self-identity within the black community forms the emotional core of the film. When an idealistic college student named Patrice (Laura Harrier) brings activist Stokely Carmichael (Corey Hawkins) to campus, an undercover Stallworth is ordered to infiltrate the rally.

This is the type of scene where Lee excels as a director, succinctly and humorously illustrating the dueling desires of his hero. A nervous Stallworth struggles to maintain his cover, even as the urge to chant “Black Power!” with his fellow agitators occasionally overcomes him. You can laugh and empathize with a man clearly out of his element; desperate to reconcile professional duty with his own social conscience.

Making matters worse, he’s enchanted by the fiery Patrice. From the surveillance van outside, his white (and Jewish) colleague Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) wonders if Stallworth can maintain his professional distance when matters of race and a beautiful girl are involved. Spoiler alert: He can’t.

Neither Zimmerman nor Stallworth is particularly concerned about their heritage. Zimmerman doesn’t even identify as a Jew, while Stallworth seems only to conduct his soul searching when Patrice pushes him. Both men would rather just focus on the police work at hand, but wallowing in the filth of the Ku Klux Klan forces them, particularly Zimmerman, to re-examine their roots. When your world is populated by genocidal maniacs, sometimes the only refuge is found in the courage of your ancestors.

Ironically, Zimmerman is the only character who really influences the story. While Stallworth weaves wild tales over the phone to local KKK chapter leader Walter (Ryan Eggold), including faux outrage over his younger sister dating a black man, Zimmerman must adopt Stallworth’s identity for face-to-face meetings with the Klan. The exhilaration of tricking the KKK is quickly dominated by the revulsion of having to swallow its racist vitriol. Threat of discovery is ever present, especially when the film’s primary villain, Felix (Jasper Pääkkönen), suspects that Zimmerman is Jewish. The script’s master stroke is that both men awaken to Zimmerman’s true heritage at the same time.

Whereas Zimmerman has Felix to push him towards self-realization, Stallworth struggles to resolve his inner conflict. This is where the script (co-written by Lee) struggles, and why BlacKkKlansman might fail to endure beyond this socially charged moment in time. Yes, Jasmine is a persistent voice in his ear, urging him to stop being “an American” and “be black”, but her character’s lack of depth relegates her to the narrative stockpile of ‘love interest’. Stallworth’s fellow white officers, particularly Zimmerman, are articulate, thoughtful, and open minded on matters of race before Stallworth even arrives. The one bigot on the police squad exists solely to make us cheer when he gets his comeuppance.

And then there are the klansmen…

Each one stupider than the next, spewing racial and ethnic epithets with nearly every breath. One character, called Ivanhoe (Paul Walter Hauser), is so stupid (and presumably stoned) that he can barely hold his eyes open or form a complete sentence. When they talk, your skin begins to crawl. And then they keep talking… and talking… and talking. So much talking, in fact, that it feels like entire scenes exist only to show how despicable they are. From a cinematic perspective, they quickly become monotonous.

Still, there’s plenty of provocation to be found in BlacKkKlansman. Most notably, Lee makes it apparent that former KKK Grand Wizard David Duke (Topher Grace) is the 1970’s equivalent of Donald Trump — albeit without the power of the presidency behind him. One’s first response might be to snicker when one character chides another that “No one would ever vote for David Duke.” That initial laughter is quickly replaced, however, by the deflating realization that America is so accustomed to hate speech that David Duke’s doppelganger is now the US President. Of course, having a few billion dollars doesn’t hurt your political prospects, but Lee’s warning about America’s festering racism is clear.It’s also a reflection of America’s current zeitgeist that both Sorry to Bother You and BlacKkKlansman feature a black man finding success by impersonating a white man over the phone. Though both films use this device for dramatically different purposes, the message is the same; only after a black man assimilates the values and mannerisms of the predominant white culture will he then be “accepted” (but even then, not really).

BlacKkKlansman is yet another urgent film with the message that America needs to deal with its ingrained racism, already. It’s also damn funny, with wonderful comedic turns from Washington, Driver, and Grace. There are the moments Lee expertly mines for sublime inspiration, as when he intercuts the recollections of a young black man’s senseless murder in the street (as told by a heartbreakingly frail Harry Belafonte) with the approving howls of the Klansmen as they watch a screening of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. That segment will linger in viewers’ consciousness. BlacKkKlansman is an important commentary on America’s painfully slow progress of dealing with its deeply ingrained racism.