I’m always grateful when European comics creators make their way across the Atlantic, so many thanks to the UK press Self Made Hero for delivering Blossoms in Autumn, a collaboration between the Brussels-born writer Zidrou and the Netherlands artist Aimee de Jongh. Their graphic novel, translated by Matt Madden, features two retirement-aged protagonists that are working at overcoming loss and loneliness to achieve their literally rejuvenating romance.

While it’s not news to me that old people like sex too, the best thing about Blossoms in Autumn is the sex scene. I say this despite usually cringing during movie sex scenes, annoyed by close-up body-double nudity and general story-halting gratuitousness. Most have nothing to do with plot tension or character development or anything but the titillation of what is apparently assumed to be a straight male audience. Often it seems even the director has hired a body double since the sex acts are shot and edited in a style out of sync with the norms of the rest of the film, e.g., slow motion pans of landscape-like close-ups cascading in and out of overlapping dissolves.

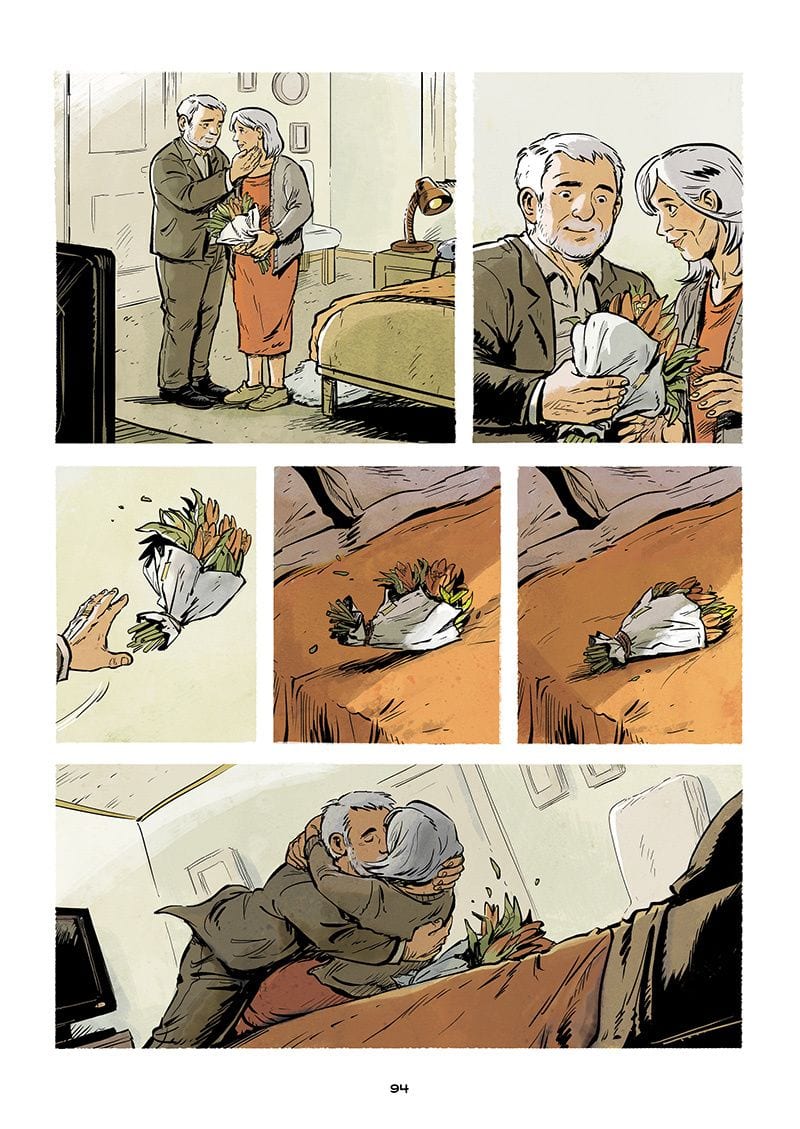

Oddly, it’s similar qualities that I appreciate in Aimee de Jongh’s double two-page spreads. After a wordless, 12-panel sequence in which her protagonists, Ulysses and Mediterranea toss a bouquet of flowers and then themselves onto a bed, Jongh changes style radically. Instead of rows of rectangular, full-color panels neatly divided by unbroken white gutters, her unframed images spill across the pages in a cascade of shifting angles, bodies fading or cropped by the overlap of images, the wrinkled bedsheets merging multiple points-of-view into gutters of webbed lines.

Instead of a painterly palette of realistic colors, Jongh suddenly limits herself to gray and white pencils and shape-filling overlays of soft browns. Where her line qualities previously vanished into story-world content, the lovers are now self-consciously drawn figures, composed of gestural lines with the shaded depth of artfully incomplete crosshatching. Eventually, even the background of the bed vanishes, and the images float as freely as figures in an artist’s sketchbook. The effect is heightened by the book designer’s use of the same images for title page backgrounds, except intensified by enlarging and cropping, giving the thickened lines an even bolder and blunter energy.

While the sex scene, both in its norm-breaking style changes and in its double placement, is the thematic center of this graphic novel, Jongh includes little nudity, focusing instead on the incremental removal of clothing and the characters’ interlocking body shapes. Mediterranea’s slip remains on throughout. This is not paradoxical prudishness. Earlier, Jongh depicts Mediterranea’s body in intentionally brutal and panel-dissecting detail as the character examines her own sagging wrinkles in her full-length bathroom mirror (with a great, unspoken reference to the Snow White phrase, “Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the fairest of them all?”).

Though the gaze within the story is her own, and the artistic hand outside the story is female too, I still felt a primarily male presence controlling the two-page spread. An earlier scene features Ulysses also nude in his own bathroom, but the moment is expressed in a single panel, with the character’s gaze inward and no mirror present. Though Ulysses is 59, only three years younger than his love interest, his own aging body doesn’t concern him or the larger story.

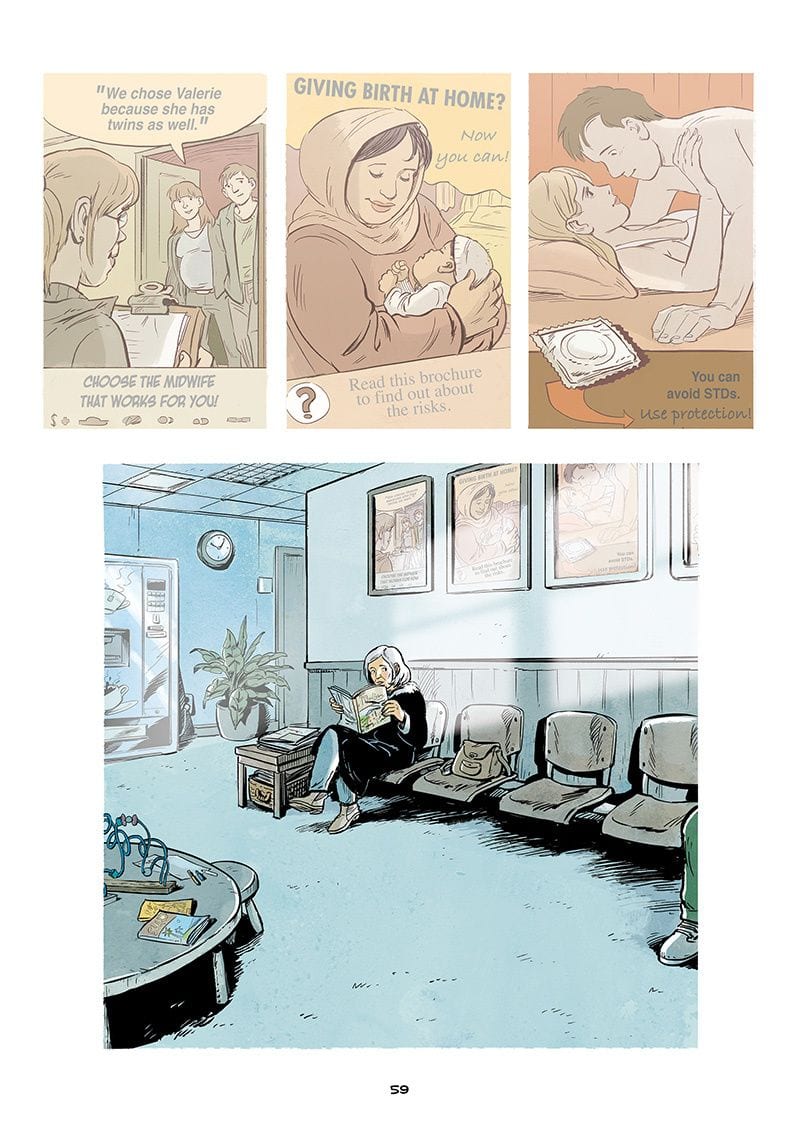

Mediterranea, however, is defined by her body, aging or otherwise. When the two characters first meet in a doctor’s waiting room, it takes her only six speech balloons to announce: “I used to be a model.” When they have lunch, she elaborates: “I mainly worked in lingerie, or nude. I had a pretty nice body when I was young.” She was featured on the cover of the French magazine Lui, which, according to Google, translates to Him, and so the title is a reference to its readership, not its subject matter.

Jongh provides several thumbnail sketches of Mediterranea’s cover issue and so tiny glimpses of her once young and pretty body. While the image suits the softporn norms it’s meant to evoke, the effect is peculiar because the lithe figure doesn’t resemble the contemporary woman at all. In fact, the figure doesn’t resemble anyone within the novel’s story world. While the character has aged, her current sags and wrinkles don’t account for the differences. It’s as if the two sets of images represent different species. With this one exception, Jongh draws her naturalistic characters on the edge of cartoon. Their feet and heads are just a little too large, their bodies a little too compressed. While not hobbits exactly, they have more in common with that stout wholesome race than they do with the alien species represented by Lui. Within the visual context of the novel, Mediterranea’s transformation is less about her current age and more about the warped and warping norms of erotic photography.

Four decades later, she still keeps a box of Lui copies because her proud father “emptied all the magazines stands and bookstores in the area to give them to all of his friends” until “he saw the pictures inside.” Ulysses is startled at first, but only because he grinningly admits: “When I was a kid, I’d swipe them from my dad! Given half a chance, I’d even jerk off to them.” This elicits a charmed grin from Mediterranea. When he purchases a copy of her cover issue from a used book store and offers it to her as a present, she asks if he masturbated to it, and though he doesn’t answer, the two share a raucous laugh.

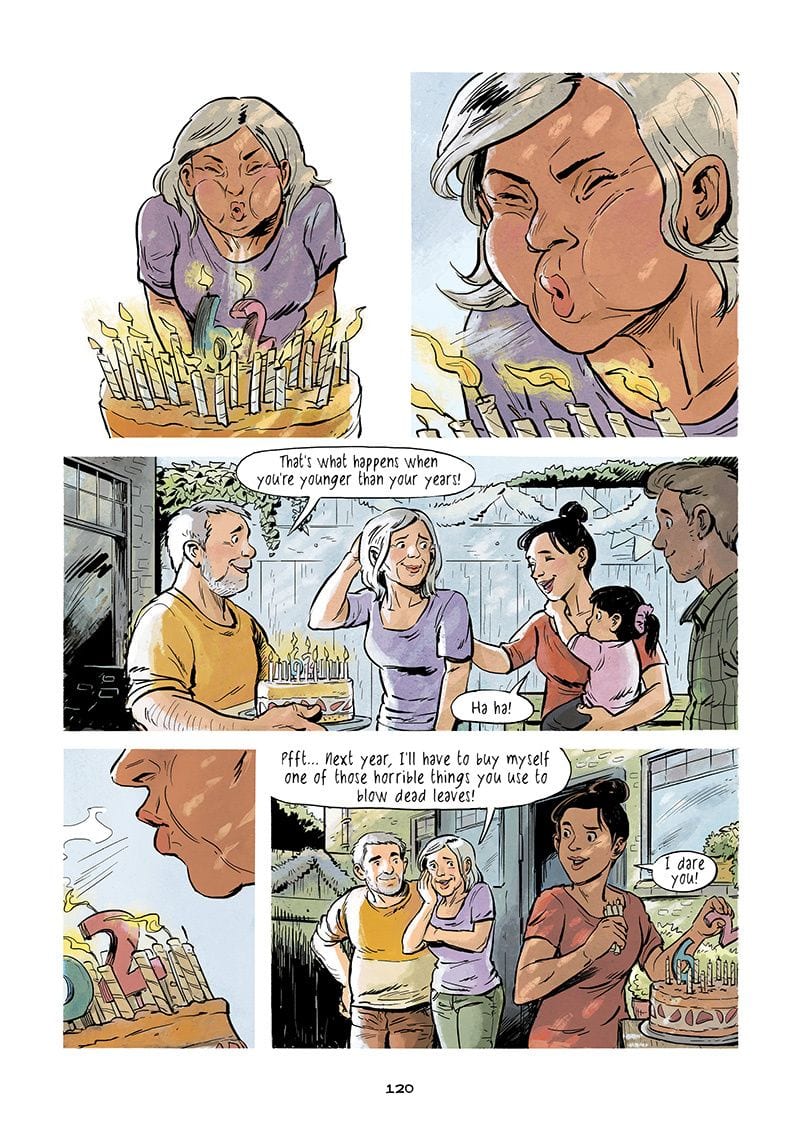

I have little difficulty accepting that Ulysses is a realistic portrayal of a 50-something European man—Zidrou after all is a 56-year-old European man. And perhaps some European readers would interpret his behavior as charming. Ulysses calls Mediterranea “delectable”, likening her to the delicious cheese she sells in her shop, and later plants “Aged Mimolette” cheese flags in her hair before planting a kiss on her lips after declaring her name “an invitation to a voyage.” The sex scene would have followed, except his kiss apparently so inflamed her blood, it reverses menopause and reignites menstruation.

While I could question Zidrou’s grasp of female biology, his understanding of female experience is more concerning. Prior to meeting Mediterranea, Ulysses’ unhappy widower routines include stopping at a neighborhood apartment to pay a woman €100 for sex. He thinks how the unnamed woman “could be my daughter” but, because of her “sweet, kind smile”, he feels she treats him “as if she were my mother.” Freudian ramifications aside, I appreciate a non-judgmental view of a sex worker, which includes a family portrait of her with her husband and two children, but then the narrating Ulysses waxes poetic about his own condom: “Who could ever express the infinite sadness of a used condom?” The image of the naked woman kneeling at his crotch unintentionally answers that rhetorical question.

Worse, any believability the character may have had is lost when near the end of the novel Ulysses arrives at her apartment to break the apparently bittersweet news to her that he’s met someone and won’t be needing her services any longer. She has to turn her back to him to hide the emotion on her face—because we are to understand this married mother of two gains deep emotional comfort from giving old men blow jobs for cash.

The age and power differences in Ulysses and his partner’s professional relationship also echo the relationship between the two authors. If this graphic novel followed the creative process of most two-author comics, the project originated with Zidrou, who penned a complete script before handing it to the 31-year-old Jongh to illustrate. If so, the characters’ questionable charms and implausibilities trace back to Zidrou. He is the lui, the him, controlling the narrative and its unfortunate notions of gender. So while there’s much to admire in Blossoms in Autumn, I’m looking forward to only one of its authors’ future books.