The pleasure of cinema is the invitation to the audience to enter a world. It’s an opportunity to vicariously “live” an experience through characters, and it doesn’t have to be high-end science-fiction such as Dune (Villeneuve, 2021), or blockbuster heroics of the DC or Marvel universes. It can be an everyday space that they’re unfamiliar with yet unlikely to experience.

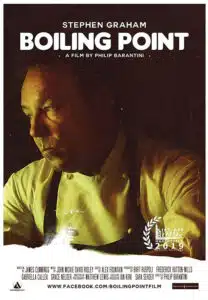

We all know that adrenaline rush of responding to pressure when time is our enemy. As much as we might or might not enjoy experiencing that feeling for ourselves, we’re drawn to stories that place characters in pressurised situations. Thus, there’s a pleasure in entering the behind-the-scenes of a top London restaurant in director Philip Barantini’s, Boiling Point (2021).

Even before head chef Andy (Stephen Graham) arrives at the restaurant for what is expected to be a busy night, the pressure is rising. Struggling beneath the weight of drug and alcohol issues, he has just moved into a new flat and is trying to make time to see or at last speak to his son. Now he must hold it together through one more night, dealing with frustrated staff and difficult customers – including one who plans to propose to his girlfriend and who has food allergies. He must also cope with his old mentor, television chef Alastair Skye (Jason Flemyng) who unexpectedly brings along scathing food critic Sara Southworth (Lourdes Faberes) as his dinner guest.

Actor-turned-director Barantini positions the cast front and centre. However, choosing to shoot the film one take sees the cinematography offer some friendly competition. An actor’s director, Barantini gives his cast control over the film’s rhythm instead of controlling it through the edit, but he still accommodates the look of the film with a singular aesthetic choice.

Boiling Point is a mood piece, and the one-take serves the narrative by not allowing the edit to interrupt the emotional rhythm of the characters. Similar to Sebastian Shipper’s Victoria (2015) and Sam Mendes’ 1917 ( 2019), it’s a means of immersing viewers into the story. In Barantini’s film, the story lasts only a matter of hours compared to the events of the aforementioned films, but the intent is the same: to use a technique to minimise audience awareness of the craft of the storytelling and create a more immersive experience.

All eyes are on Graham, who unsurprisingly, delivers a powerful performance. His gift as an actor is that he can be ferocious and intimidating, and yet he can also be vulnerable. It’s a nuance that makes him captivating to watch and one of the most accomplished actors working at his craft today.

Graham is supported by a strong cast, led by Vinette Robinson and Ray Panthaki. Together they create a family dynamic, and beneath the fiery temperaments and heated words, they care about one another as a family cares for its own. Graham and his right-hand chef Carly (Robinson), and chefs Freeman (Panthaki), and Emily (Hannah Walters), mimic older siblings. The owner’s daughter Beth (Alice Feetham), who manages the restaurant, resembles a stepmother. Her role is not conceived as such, but that dynamic creeps into the drama and creates a genuine milieu.

Barantini approaches the antagonisms of the drama with skill. Instead of putting Andy’s troubles front and centre, he introduces them and then sets them to the side. As the pressure of the night builds, we’re aware of Andy’s underlying anxieties, and Bartini references Andy’s living situation and relationship with his son sparsely. Andy is frequently shown drinking water that stirs in the audience a fear that he’ll lapse and reach for the bottle.

However, the underlying personal issues aren’t emphasized unnecessarily; rather they’re used to nurture simmering suspense of other plot strands. Will Andy honour his promise to Carly and speak to Beth about a raise? Will Alastair’s presence tip Andy, the restaurant, and its staff past the breaking point? The story is blessed to have touching humane moments, that offer a deep breath amidst the chaos, with head pastry chef Emily and her commis (junior) pastry chef Jamie (Stephen McMillan) sharing a powerful emotional interaction.

If we’re to look for a deeper resonance this story will have with audiences, then it’s how Andy serves as is a jumping-off point for the, “I’m too busy” rhetoric. Too many of us allow our work to drive us, and we fail to take enough time out for ourselves or other people. Sadly, the structure of society makes it difficult to take the alternative approach, often for financial self-sufficiency.

Boiling Point also explores how beholden we can be to what other people think of us. We care what will and can be said about us on social media, and we appease people who wield their opinion with a passive-aggressiveness as if it were a weapon. Boiling Point is set in a specific pressurised environment, but it taps into the “rat race” where the work-life balance is askew, not only to our detriment but that of others.