Both critical and popular opinions about particular films often change, sometimes significantly, over time. Consider BFI’s Sight & Sound Poll of the Greatest Films of All Time, conducted every ten years since 1952: in 2012, Vertigo topped the list, but Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 film was not even included in the top ten in the 1962 and 1972 polls.

To take another example, Vittorio de Sica’s 1948 Bicycle Thieves topped the 1952 poll and was #7 in the 1962 poll, but has never been included in another top ten. Popular opinion also changes with the times, as is clear from films that initially disappointed at the box office, like It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) and Raging Bull (1980), which are now considered classics.

Critic’s polls and box office statistics are only part of the story when considering any film’s place in cinematic history. Michael Curtiz’s 1942 film Casablanca never cracked the top ten in a Sight & Sound poll, and it was on the lower end of the top ten highest-grossing American films of 1942. (Granted, box office statistics from that period were calculated differently than they are today.) But it scooped up three Oscars (Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay) at the 1943 Academy Awards, and since then has enjoyed sustained popularity that was unexpected even by its creators.

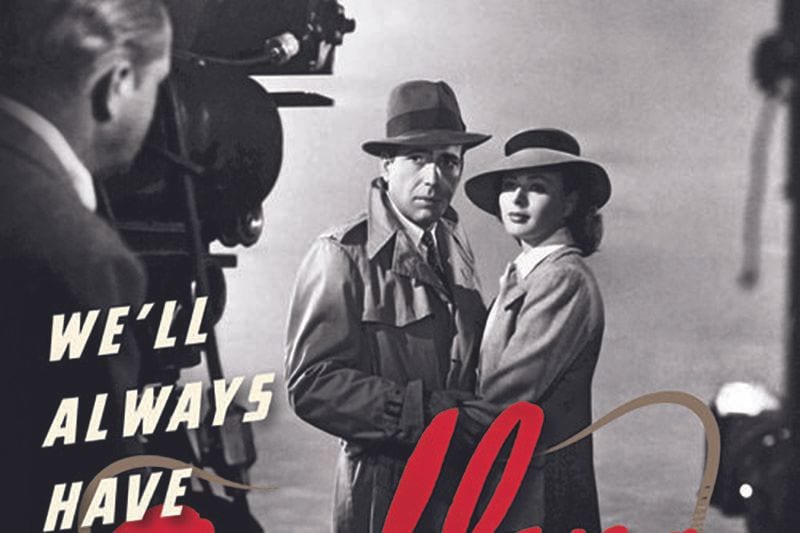

Casablanca’s enduring popularity is the justification for Noah Isenberg’s latest book, We’ll Always Have Casablanca: The Life, Legend, and Afterlife of Hollywood’s Most Beloved Movie. You can quibble, of course, as to whether Casablanca is truly “Hollywood’s Most Beloved Movie”, but it’s an inherently subjective judgment to begin with, and you’d be going up against an author whose encyclopedic knowledge and infectious enthusiasm would make him one tough opponent. Fortunately, even if you don’t agree with Umberto Eco that “Casablanca is not one movie; it is ‘movies'” you can still learn a lot by reading Isenberg’s book and have a great time in the process.

Casablanca has so much going for it: great stars like Bogart and Bergman, a fine cast of supporting players like Claude Rains, Conrad Veidt, and Wilson, a story that resonated with an audience whose country had recently become involved in the war, and above all a script loaded with memorable lines too well-known to bear quoting here. Given the film’s emphasis on dialogue, it is perhaps not surprising that Casablanca had its origins in a play, Everyone Comes to Rick’s, written by Murray Burnett, an English teacher in the New York Public School system, and his writing partner Joan Alison, whom Isenberg describes as “a divorcee with three small children.”

Although it’s full of intriguing details, Isenberg’s chapter discussing the origins of the screenplay reads oddly, in part because he can’t seem to decide which role was played by Alison in creating the play. At times he seems to believe that Burnett was the only real writer while the contributions of Alison, his writing partner, were more supportive: according to Isenberg, she “read Burnett’s work, offered him her wisdom, and shared her network of precious contacts within the New York drama scene.”

That sounds more like a beneficent aunt than a writing partner, and is contradicted a few pages later by a more specific description of their working style: Burnett “would plant himself at the typewriter, hunting and pecking, while she paced, smoking one cigarette after the next, dictating dialogue aloud.” That sounds like Alison was making at least as great a contribution to the writing process as Burnett, and certainly that she was doing far more than simply supporting him emotionally or providing professional contacts.

While Burnett and Alison created many of the characters and situations in Casablanca, the finished screenplay was the work of many hands, as is often the case in Hollywood. Twins Julius and Philip Epstein produced some of the film’s most memorable comedic lines, while Howard Koch wrote many of Rick’s lines and provided a serious political counterpoint to the twins’ sparkling wits.

The benefits of combining their contrasting approaches can be seen in the scene in which Rick turns down the offer of a rival, Ferrari (Sydney Greenstreet), first to buy his nightclub and then to “buy” Sam (Dooley Wilson), who plays in the club. The first two lines were written by Koch, establishing Rick’s moral character and Ferrari’s lack thereof, while the third, written by the Epsteins, adds a touch of comedy and cynicism to an otherwise serious and straightforward exchange:

Ferrari: “What do you want for Sam?”

Rick: “I don’t buy or sell human beings.”

Ferrari: “Too bad, That’s Casablanca’s leading commodity.”

Selectivity is not one of Isenberg’s virtues, at least not in this book, as he assumes you want to know anything and everything about Casablanca. He’s at his best when relating lesser-known bits of information and at his worst when rehashing information that is already well-known. For example, one chapter is devoted to biographies of the film’s principal and supporting actors, combined with an account of the casting process.

Isenberg doesn’t provide much in the way of revelations concerning the lives or careers of Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, but he does include some interesting and less well-known information about Arthur “Dooley” Wilson, who had an extensive career as a drummer and actor before coming to Hollywood. Fun fact: his nickname came from a stage number in which he played a stereotypical Irishman, in whiteface, and sang a song called “Mr. Dooley”.

We’ll Always Have Casablanca is a book for fans, albeit one based on extensive research (with almost 30 pages of endnotes to prove it). The ideal reader for this volume is someone who loves Casablanca and is willing to skim past sections that seem unnecessary or simply peculiar and reveling instead in the wealth of information provided by the author.