In his definitive history, Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music, Rob Young identifies two significant vantage points that intermingle to form the ideological foundation for the eclectic mix of historicism and experimentation, pastoralism and futurism that was the English folk revival. First, there was the “fear of annihilation” of the nuclear age, of “technological progress, and a vision of alternative societies filtered through popular and underground culture” which promoted the idea of “getting back to the garden”. Such anti-apocalypticism was the fuel for much late 20th-century popular art, which often celebrated both nihilism and escapism (often to an idealized past) in equal measure.

Then, Young reminds us, there is the fact that “the great age of folkloric retrieval is synchronous with the age of Karl Marx”, and that the term “‘Folk’ in Britain has always been contested territory.” By the time of the post-World War II national interest in Britain’s folk heritage gained strong public sentiment as an extension of national pride, its identity was already in flux and open to often radical or revolutionary interpretation and application. “No longer” Young contends, “does the word [folk] refer solely to particular songs and melodies attached to the ancient lore of the land; nor to techniques of singing, instrumentality, and delivery; nor to a music’s sense of belonging to small, often rural communities…. Folk still includes these preserved traditions, but it is also applied to areas of contemporary music.”

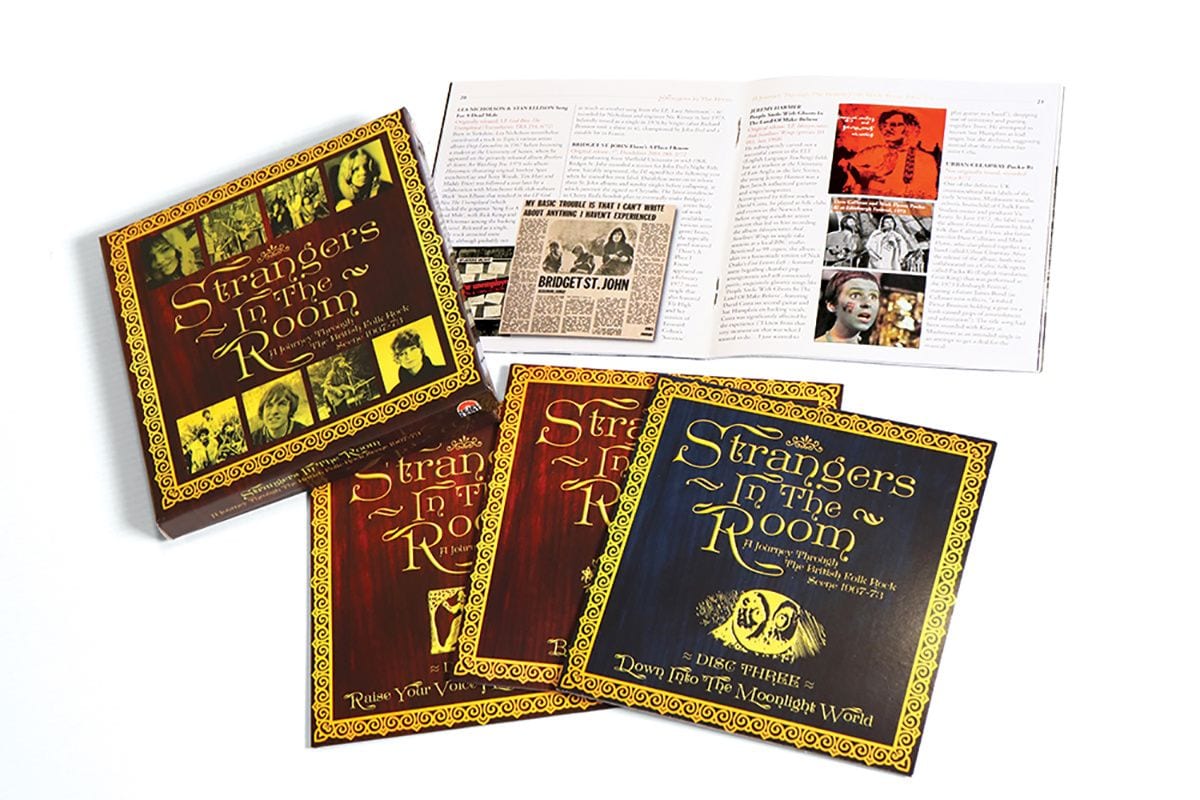

Strangers in the Room: A Journey Through the British Folk Rock Scene 1967-1973, the latest collection of British folk-revival music of the 1960s and early 1970s from master-anthologist David Wells and Grapefruit Records demonstrates the amazing variety of approaches to the folk tradition as it clashed against the ever-evolving wave of popular musical influences better than any previous anthology of the era. While it might be considered a sequel to Grapefruit’s 2015 release Dust on the Nettles: A Journey Through the British Underground Folk Scene 1967-1972, this collection sets itself apart from the earlier anthology through its focus upon the evolution and, perhaps even more accurately, mutation of Britain’s folk music as these young musicians attempted to merge old and new, to invert traditions, and invent new sounds and directions.

Some of those new directions, of course, would shape popular music through the 1970s and into the 1980s and beyond, becoming in themselves classic signposts in the evolution of popular music. Fairport Convention, now legendary but as late as the 1980s still a cult band, is at the lead of this group, appearing here with “Sir Patrick Spens” and with their equally legendary, tragic lead singer Sandy Denny closing out the whole of the box set with the now beloved “Who Knows Where the Time Goes”. Others now highly regarded who necessarily appear here include Steeleye Span, Pentangle, Bill Fay, Matthews Southern Comfort, Joan Armatrading, and the Incredible String Band (with a gem in their previously unreleased 1972 song “Oh Did I Love a Dream”). The last group, in particular, made up of the stylistically anarchic Mike Heron and Robin Williamson, has grown in stature as their influence upon everyone from the Beatles to Led Zeppelin has come to be understood long after their recording peak.

But it’s worth remembering, and this set presents the necessary contemporary context, that this was, in its time, outsider music that took time to find its way to any cultural center. Indeed, the most commercially successful musicians of this age and scene, like Pink Floyd and Steve Winwood/Traffic worked on its periphery, gathering the necessary influences to break big. In fact, Floyd’s Nick Mason and Richard Wright appear here with the 1970 outfit Chimera on “Sad Song for Winter”, one of the set’s highlights that, until now, has remained unreleased.

Some of the set’s best pieces are from those performers more influenced by the times than influential thereafter. While often derivative of the deservedly better-known and more successful performers of the age, these pieces nonetheless offer near-perfect distillations of time and mood. Jade’s lead singer Marian Segal evokes Sandy Denny’s crystalline tone on “Among Anemones” from that band’s lone 1970 album while Rod Edwards’ driving electric bass guitar elevates the whole and evokes the later, harder rocking work of Steeleye Span. Dando Shaft’s “Riverboat”, too, is clearly influenced by Fairport Convention but, with Polly Bolton’s strong vocals, forges a more demanding, contemporary sound.

Spyro Gyra’s “Dangerous Dave” fits the anti-military spirit of the times with its wry and naughty gun references. Trader Horn’s Beatlesesque “Here Comes the Rain” is simultaneously uplifting and moody, which is also an apt description for the Strawbs’ “The Man Who Called Himself Jesus”. Other pieces could only have been created amidst this fertile stew while standing quite at odds with the dominant sound. Consider Mike Hart’s abrasive, caustic “Almost Liverpool 8” or Jeremy Harmer’s lonely psychological descent in “People Smile With Ghosts in the Land of Make-Believe”.

This is also a fascinating collection for musical archeologists looking for early appearances of musicians who would go on to, if not fame or fortune, at least higher-profile gigs in later years and other genres. The beloved Scottish entertainer Billy Connelly appears with his folk outfit the Humblebums (which also featured the late and well-regarded Gerry Rafferty). Peter Bramall (better known by his later nom de plume Bram Tchaikovsky) plays guitar on the wonderful “Hanging Tree” by the unfortunately named OO Bang Jiggly Jang. Robin Scott, who would create one of international pop’s greatest one-hit-wonders when, as M, he released “Pop Musik” a decade later, appears here with “The Sailor” from 1969.

Of course, with a collection this size, not all of the experiments work, or, even when they do, don’t always lead to brilliance. The set, in its scholarly completeness, does point to one unfortunate evolutionary offshoot of the folk-rock explosion: the development of what would become “soft rock”. Several tracks here, including Unicorn’s “I Loved Her So Long”, Daylight’s “Lady of St. Clare”, Knocker Jungle’s “I Don’t Know Why”, and Storyteller’s “Morning Glow”, document that stylistic turn. Pleasant little songs, each and every one, but their ilk would, in only a few years, go on to spread like the kudzu that has taken over the American South, a good idea at the time that has grown into a perpetual nuisance.

But it is not despite but because of its mix of stormy failures and exquisite successes that Strangers in the Room is a must for1960s Anglophiles. These fascinating sounds continue to resonate today.