It’s not giving anything away to reveal that the title of Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore‘s work is a variation on “bottom feeders”, the racist nickname for folks from the semi-fictional Bottomyards district of inner Chicago. As the main character Darla says, “Bottomfeeders come in all types”—including, readers slowly discover, the giant slithering kind.

Though her father grew up in the area and is financing her as she tries to make it as a fashion designer, Darla and her white roommate Cynthia are fresh from art school and moving into a soon-to-be-gentrified apartment complex. Except why aren’t there any windows? And what are those noises inside the walls? And why is that freaky white guy always lurking at the entrance? And… are those entrails in the toilet?

Based on BTTM FDRS‘ race-fueled, sci-fi/horror premise, Daniels would find a happy home on the writing team for Jordan Peele’s recently rebooted Twilight Zone. He’s well partnered with Passmore whose art is also all about color—in both senses. It’s a diverse cast, but Passmore tellingly avoids the most common marker of ethnicity: skin color. Old school comics color separation produces blocks of solid hues divided by object shapes: shirt, face, hair, background wall. Photoshop makes the technique that much easier, but Passmore twists it for more subtle effects, filling whole panels and pages into single colors, with internal shapes varying only by degrees.

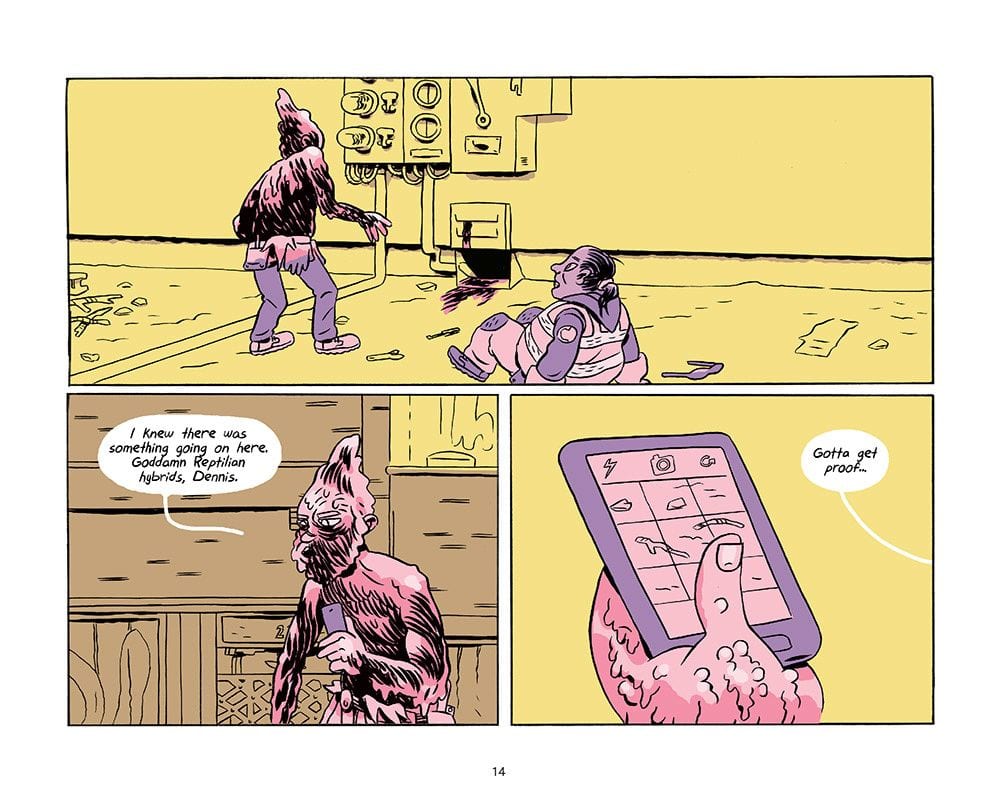

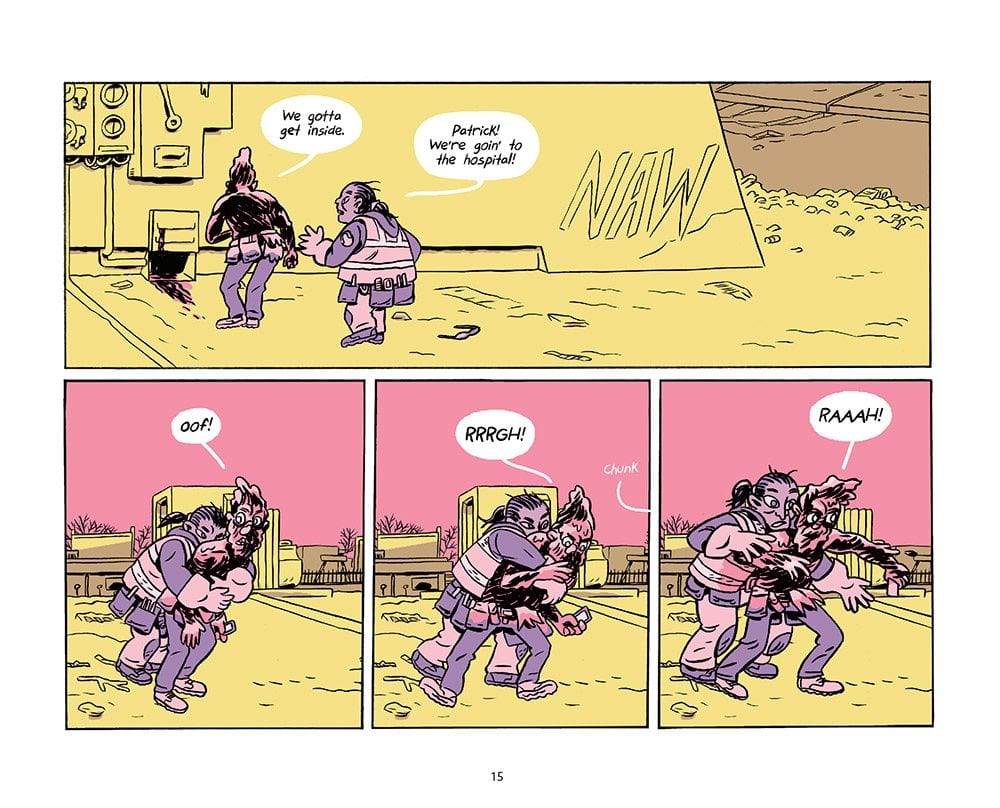

The approach seems natural enough at first, usually suggestive of changing light sources as characters move from windowless room to windowless stairwell to windowless basement. But why is the hallway all greens? And when the panels later vacillate between all purples and all yellows, is that because the light fixtures are pulsing like police strobes? If so, why doesn’t Passmore draw the fixtures—and why doesn’t Daniels write dialogue so that we know that the characters notice it too? The effect is quietly surreal, an unacknowledged ambiguity darkening the fabric of the story’s already horror-tinged reality.

(courtesy of Fantagraphics)

Passmore’s characters are cartoonish, but not outlandishly exaggerated and so not able to break the bounds of their otherwise naturalistic world. Though cartoons often morph to reflect their character’s internal thoughts and emotions, Passmore’s characters are consistently solid. Instead of drawing a violence-obscuring dust bubble around the exploitative white landlord as he’s dragged through a too-small opening, Passmore lets us witness arms popping from shoulder sockets in atypical cartoon gore. His cartoons also never break from their story’s prison-like panel gutters, which vary but mostly maintain a loose 2×2 base pattern. Interestingly though, Passmore orientates the entire book 90 degrees so that the spine is bound along what would normally be the top edge, producing wide instead of tall pages. The story literally goes sideways.

For all the novel’s early creepiness and eventual full-blown monstrous spectacle, the real horror bubbling beneath its white gutters is a different kind of whiteness. As her new neighbor, the problematically ironic rapper Plymouth Rock, tells Darla: “Can we just agree for now that the real threat is white people?”

He doesn’t mean they’re a threat in the Charlottesville Klan rally sense. Probably the 911 dispatcher wasn’t trying to be racist when she tells Darla: “You’re calling from the Bottomyards. We can’t send a car all the way down there unless there’s an actual emergency.” And Hadley, the white woman who might hire Darla and Cynthia for her fashion firm, she just doesn’t know any better when she remarks: “You live in the Bottomyards now? Jesus, aren’t you scared? That part of town is like a WAR-ZONE! … I have a friend who drove through there once and it was like crazy!” And doesn’t Hadley practically make up for it when she decides to rent an apartment in the complex for her visiting designers: “For, like, a totally AUTHENTIC Chicago experience, you know?”

Sadly though, the worst among them is Cynthia, the prototypically good-intended but clueless white liberal who thinks having a black friend is basically the same as being black: “I know I wasn’t the one they called the n-word in elementary school, but I was usually right next to you when it happened, and it was embarrassing for me, too.” After Cynthia refuses to move in as planned, fawns over Julio (Plymouth Rock’s actual name), and uses Darla to score cool points with Hadley, Darla dumps her. Cynthia returns the next day with her version of an apology, which ends with a familiar refrain: “But that doesn’t make me a racist, and I’m like super hurt that you think that. I’d feel a lot better if you apologized, too, actually. For calling me a racist.”

(courtesy of Fantagraphics)

Spoiler Alert

What’s this have to do with the entrails monster haunting the building’s vents? Literally everything. Readers wary of spoilers, you are duly notified. It turns out there’s a reason for the complex’s hidden surveillance cameras, lack of windows, and general prison-like architecture. It’s a prison. Or was. I won’t recount the entire backstory (it’s even weirder than you’re thinking), because it’s all a pleasantly elaborate conceit to reflect back on Cynthia and the world of white privilege she represents.

A wall of walking entrails, the ultimate bottom feeder, is awakened by the influx of new excrement to eat and, when Cynthia wanders through the wrong broken hatch, it merges with her. As the gently deranged son of a former tenant explains: “It’s a BUNCH of things all living in symbiosis. … I’m thinking that’s what happened to your friend. She got sucked into the symbiosis.” In addition to straight-up horror trope, symbiosis is a good metaphor for US race relations. Call it the deepest, darkest entrails of white privilege that need to unconsciously believe in black inferiority to survive. Or as Cynthia remarks as she’s hanging from the ceiling: “It’s uncomfortable but like not in a bad way. I don’t know what it’s putting in me, but it makes it feel okay.”

Of course, she feels okay. She’s had her black boyfriend to lovingly undermine her entire white life. The monster just makes that literal, killing Julio in a jealous rage, blocking the exit when Darla tries to flee, resulting in yet another ineffective apology: “Ugh, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to do that, either. I saw you running toward the door and couldn’t help it.” Since Cynthia is incapable of changing her own monstrousness, it’s up to Darla to save them both, resulting in Daniels’ two best lines of dialogue in the novel:

“Cynthia, I have an idea,” says Darla. “I’m not gonna tell you what it is though because you’ll probably subconsciously sabotage me.

“I don’t know why I keep doing that.”

Of course, she doesn’t. That’s the whole point of white privilege. And that’s the whole point of horror — to drag up our culture’s biggest, ugliest globs of unconscious sewage and spread it across a white page for us to see and acknowledge. Ultimately, Daniels and Passmore are optimists though, opting only for a temporary kind of horror, the sort that resolves in hospital bedrooms instead of sealed basements. Even Passmore’s color scheme reboots to the comics standard, a range of blues and greens and yellows and reds, all in the same happily integrated panels. Until the very last page offers a final, purple warning to Cynthia …

(courtesy of Fantagraphics)