Cabaret Voltaire have come a long way. The band which was formed in Sheffield, England in 1973 are coming up on their 50th anniversary in a few years. Richard H. Kirk, the sole original member continuing to perform and record as Cabaret Voltaire, half-jokingly wonders whether the early material they produced even ought to be called music. Ranging between dark soundscapes, discordant cut-up experimentation, and post-punk groove, the band’s oeuvre – like many in that post-punk, nascent industrial scene – defied clear categorization. Early pioneers of sampling, they cast their net widely, integrating reggae, African beats, and more.

Originally a trio (Kirk, Stephen Mallinder, and Chris Watson), their impact was visceral. Early shows sparked riots, yet by the 1990s they had achieved the status of post-punk legends. How does such a shift occur? It requires more than longevity. To put a spin on the title of their latest re-release, it often boils down to a delicate balance between chance and causality (bound by lots of hard work). Plenty of other remarkable bands from the period flared and vanished into the creative murk which was the 1980s. Where does that leave outfits like Cabaret Voltaire, who chose not to go quietly into the night but continue to challenge convention on stage and studio alike defiantly?

Two collections of long-forgotten (if not quite lost) Cabaret Voltaire material were released last week, with a brand new album to follow in the new year. The juxtaposition is a fitting one, book-ending more than four decades of work by this iconic and iconoclastic band.

Pink Fender by rahu (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

From hostility to positivity

When we spoke, Kirk reflected on how much things have changed, from his vantage point as a performer on stage.

“In the very early days of Cabaret Voltaire, there was a lot of hostility. The first-ever live show in 1975 ended up in a mini riot. People were that freaked out by the music that they attacked us. We played to some punk audiences in ’76, ’77 and again you just got spat on, and it was very hostile — because even though initially punk was liberating, then it became too restrictive. If you didn’t play a punk kind of thrash with two chords or whatever, then people didn’t like it.

“But then all of a sudden it seemed to change towards the late ’70s, and we were getting a more positive reaction. And I could say that the live shows that I’m doing [now] all seem to get a very positive reaction. People have got the perseverance to sit through the 60- or 70-minute set. They don’t leave, some of them even dance. I can’t complain!”

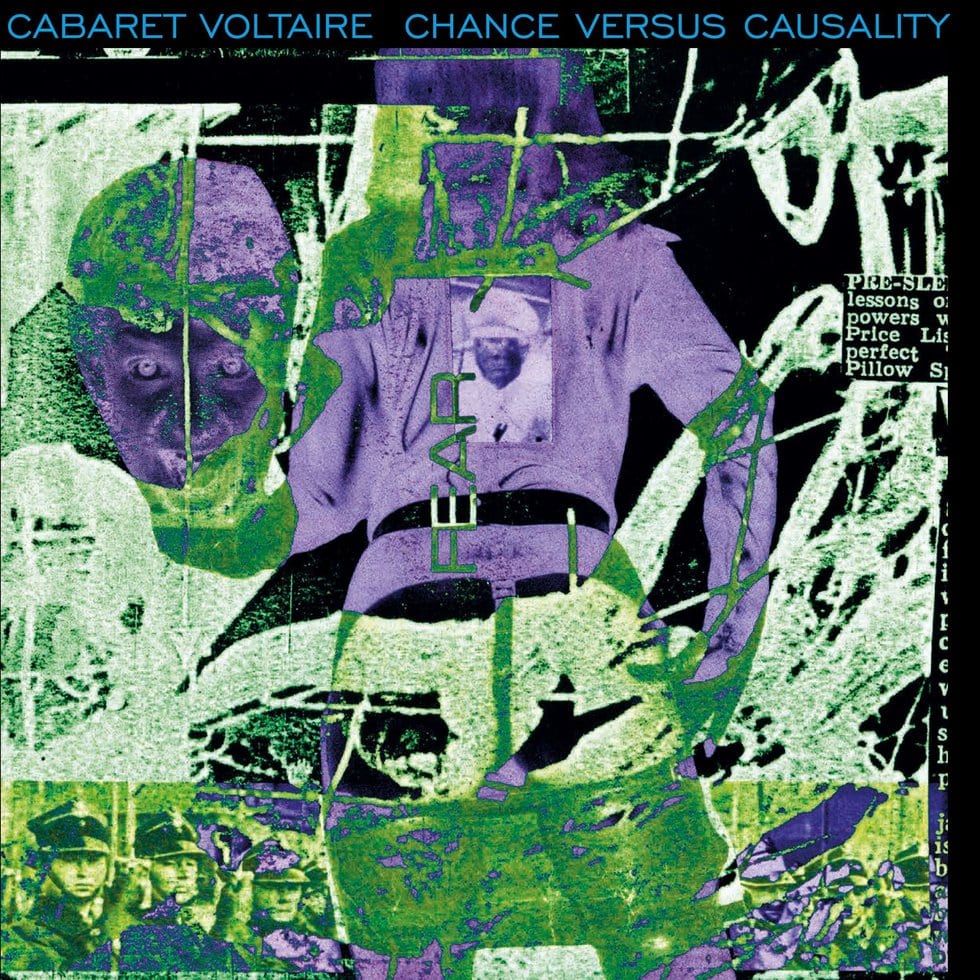

Chance Versus Causality

One of the Mute Records re-releases coming out this month is the long-forgotten film soundtrack Chance Versus Causality – a soundtrack Cabaret Voltaire produced for a film they never even saw.

The genesis of the darkly discordant soundtrack was a remarkable event in Brussels in 1979 at a venue known as the Plan K. It was an old sugar refinery converted into an arts center, and Cabaret Voltaire was invited to perform alongside Joy Division, legendary writer William S. Burroughs and artist/performer Brion Gysin. For Joy Division, it was their first gig outside of the UK, as well as the first live debut of their iconic song “Love Will Tear Us Apart”.

The trio were already good friends with Joy Division, having performed other shows with them. The relationship also had its utilitarian aspects – Joy Division had a van, and Cabaret Voltaire did not, so Joy Division took charge of transporting the bands’ gear.

Kirk recalls that they traveled to the show by hovercraft, which was rather exciting for them at the time, but it was exciting in other respects as well. He’d been a fan of Burroughs for several years, so the chance to meet and read with him was a definite lure. In the end, he was too shy to make much conversation with his muse, and they resorted to discussing the work of Genesis P-Orridge, a mutual friend and member of the outfit Throbbing Gristle.

“When you meet someone like that, it’s like you don’t really know what to say, you’re a bit in awe,” he recalls, laughing. “But it was a great event, I remember there was free champagne and food, and it was all very sociable and a bit crazy. In one room they were showing some films that Burroughs had made with Anthony Balch — The Cut Ups and Towers Open Fire — which was fantastic because I’d never seen them before.”

One of the other people Kirk and his bandmates met at the event was filmmaker Babette Mondini. She was already a fan of their work, and when they met again at a show in Amsterdam not long after, she asked whether they would be interested in doing a soundtrack for a film she had made.

“It was apparently a 16mm film with split-screen using two projectors. And basically, that was about as much as we knew,” Kirk explained. “We hadn’t seen the film, and I still haven’t seen it to this day, forty years later. I think initially she was a bit disappointed because she really liked the single that we had out called Nag Nag Nag, but we didn’t want to do something like that. We wanted to do something a little more free-form.

“So we made the soundtrack, it was mainly improvised live in the studio, and we just sent off the two reels, the quarter-inch analog tape, and that was where the story finished.”

Fifteen years later, the soundtrack re-entered Kirk’s life when a mutual acquaintance found it and made a digital copy that made its way back to him.

“I just sat on it for 15 years, and then it seemed an appropriate time to release it, as Mute were going to release some other older Cabaret Voltaire work,” he said.

How do you make a soundtrack for a film you haven’t seen and know next to nothing about?

“I don’t know!” chuckles Kirk. “We just imagined there were quite a few talking heads in the film, people just talking about various things, and really we just did what we felt would be appropriate.”

Kirk says they were very much into the idea of soundtracks at the time and wanted to explore the abstract nature of the genre. Kirk’s influences included the soundtrack to the David Lynch film Eraserhead, as well as the soundtrack to the Texas Chainsaw Massacre — “quite atonal and kind of strange.” They hit the studio, improvised, and the result was Chance Versus Causality.

“To me, it’s a little bit of a lost classic,” says Kirk. “Some of the sounds are reminiscent from the Voice of America album which was made around the same time. But it was more tape orientated rather than rhythm. When I dug it out and started to listen to it again before it was mastered, I was pleasantly surprised. I mean I’d listened to it when I got ahold of a copy 15 years ago but I’d just totally forgotten about it, and when I revisited it I was really pleased with what I was hearing.”

“Up to no good”

In addition to Chance Versus Causality, Mute Records is also releasing the first-ever vinyl edition of a collection of early tracks by the band, 1974-76. The album first appeared as a cassette-only release on Industrial Records in 1980; it received a CD reissue from Mute in 1992 and now moves to vinyl. It hearkens back to Cabaret Voltaire’s early experimental period, with tracks that defy normative song structure, rich with samples and droning, darkly atmospheric loops punctuated by piercing eruptions of beat and rhythm. Yet there is something about the neatly balanced juxtaposition that anchors it firmly and identifiably in the spectrum of Cabaret Voltaire’s broad-ranging sound.

“It’s kind of weird going back and talking about the past and reliving it,” Kirk reflects. It’s something he’s found himself doing more often, in light of re-releases of both Cabaret Voltaire material as well as his own work. When it comes to the material on 1974-76, he recalls going to bandmate Chris Watson’s loft every Tuesday and Thursday evening, where they would often record two or three pieces of music in a single night.

“Because we couldn’t read music, the obvious thing to do was just commit everything to tape,” he reflects. “Luckily, those tapes were preserved and kept. It was the early days, the formative times of Cabaret Voltaire.”

“A lot of that music — I don’t know whether music is the right word — it was mainly using tape recorders. We did start to introduce instruments in there but were trying to base it around tape loops. Atmospheric would be a word that I would use to describe it. It was 1974, I was 18 years old, the other two guys were slightly older than me, but we were just young people, and we were just up to no good. We wanted to make mischief and create the idea of making non-music – that was the word that Brian Eno used to describe it. He was trying to say that anyone could make music, you didn’t have to learn an instrument, there were other ways to do it. I think that was quite influential really, that idea because none of us were very musical back then.

Photo courtesy of Mute Records

“Some of it makes me laugh,” he chuckles. “When you have something like “Do the Snake”, which was I suppose us trying to do a dance track. I listen to it now, and it makes me smile. And some of the other pieces, it’s almost like: ‘we had the audacity to do this!’ There were no rules, or if there were rules, we’d break them.”

Nevertheless, he thinks most of it has stood the test of time, to the point where contemporary musicians often seek to replicate their sound using modern computers. It wasn’t the quality of the recordings that mattered, he says – the ideas were what carried the material back then, and which still give it meaning today.

The over-reliance of contemporary musicians on their digital toys sometimes comes at the expense of meaningful ideas behind the music they produce, he feels. There are too many people making music these days, he quips. It’s not that he feels it should be an elite club, but rather that the ease of producing music today using computers means it often comes at the expense of originality. Whereas in the mid to late 20th-century musicians like Cabaret Voltaire often took creative and iconoclastic ideas and then struggled to figure out how to express them in sonic form, today’s world is often characterized by the opposite: easy music, but a dearth of creative ideas.

“Anyone who has a laptop or a computer can easily get software, and it almost does it for you. I think there’s less talent required in some respects. I think the main thing really is the ideas, the ideas are important. If you’ve got good ideas, it doesn’t matter if you’re making music digitally or whether you’re banging on a tin can. I think a lot of music these days tends to sound like it’s been made using the same program. I have mixed feelings. I mean I’ve been using a computer and software for 20 years or more, but again I think it’s back to the ideas.”

“There’s something about the physicality of a needle hitting the groove…”

It’s not just the ease of making music that renders Kirk suspect of the way modern technology is sometimes used. The use of digital and online sound as a delivery medium has re-shaped the way audiences listen to music, and not necessarily in a good way. For a band which excelled at concept albums, the industry- (and more importantly, the listener- ) shift toward singles has come at a price, he feels.

“I hate Spotify, even though some of my music is there. I hate the fact that albums have died. I always considered myself mainly to be an album artist. For me, there’s nothing better than you buy an album that you like, and you listen to it the whole way through because it’s telling you a story. I think that’s kind of gotten lost now because people tend to fixate on just single tracks. That’s partly due to iTunes. When the internet came along, it trashed everything for a lot of artists, because people weren’t buying music anymore. And then iTunes came along, and they found a way to monetize it, but they insisted that you must be able to download each individual track rather than just buy the whole thing. I always thought that sucked, personally.”

He cites Chance Versus Causality as an example of an album that is best listened to in its entirety in a single sitting. He had to break it into parts for the vinyl release but feels there are positive trade-offs to being able to listen to music on vinyl.

“Vinyl was always my preferred mode. I think there’s something about vinyl where you’ve got the physicality of a needle hitting the groove, whereas with a CD you’ve got a laser playing across a disc. There’s a physicality to vinyl, and I think bass always sounds better off a vinyl record. To me, it feels more physical or earthy, whereas CDs are always very clean. Record companies have started releasing vinyl again because they can make money. I like the result — the money thing aside, if people decide to get into vinyl again, that’s no bad thing. Personally, I’ve never downloaded any music from iTunes or anywhere else, and I always thoughts MP3s sounded rubbish — really thin. I don’t mind CDs. If I’m buying any new music now, it will generally always be a CD or vinyl. Plus you get artwork, which you can look at, and you can see the credits, and who did what, whereas with downloads I don’t think you get much information as far as I understand.”

“It’s more necessary now to be politicized”

In an interview with Mick Fish conducted in 1983 (included in Fish’s 2002 book Industrial Evolution: Through the Eighties With Cabaret Voltaire) Kirk comments that he’s often leery of bands that engage in political preaching, and yet “Mind you, I think we are more political than any of those people, purely because what we are advocating is individualism.”

Three and a half decades later, Kirk says that stance in defense of individualism is more important than ever.

“I think it’s even more necessary, given the rise of what people call populism — I tend to say it’s fascism. There’s been a real big swing to the right, in America, for instance with Mr. Trump and we have now a very right-wing government in the UK, with this business with Brexit. Also in Europe, you’ve got Austria, Hungary, Poland, and Italy. They’re all turning to the right and scapegoating immigrants. And all I can say is: that’s how Hitler started. So it’s not good. I think it’s more necessary now to be politicized.”

At the same time, he says, it’s important as an artist to be careful how you do it. Sometimes the type of direct, didactic approach can backfire. Hence Cabaret Voltaire’s efforts to produce material that causes people to reflect, and to cultivate that sense of individuality and autonomous thinking.

“You don’t want to end up just ramming slogans down people’s throats. I kind of liked the Clash back in the day, but I was a bit unconvinced by some of the sloganeering that some of those guys did. I’m in a dilemma now — I’m making a new Cabaret Voltaire album, and I feel it’s even more important, in this day and age, that you do deal with politics. But the problem is that things move so quickly. So maybe you have a political theme to the album, but by the time it gets released things have changed again.”

Like other musicians who came of age railing against the UK’s conservative turn under Margaret Thatcher and other right-wing politicians, Kirk can’t help but note the troubling irony in the fact that many of the dystopian elements they used in provocative ways back in their earliest days have now manifested in reality.

“Because of the whole fake news now, it’s almost impossible to believe anything that politicians say. There’s just this process of denial — someone will come out with a really racist statement, and then they’ll just say they were only joking. I find it quite scary. I think it’s like a lot of the things we were writing about back in the 1970s, these kinds of dystopian ideas. That whole concept of surveillance — even now in England they’re introducing facial recognition cameras without even getting permission, without telling anyone. And in an even bigger way, it’s going on in China, that kind of thing. All this high tech stuff is being used for really dark purposes, instead of to benefit society. Instead, it’s being used to subdue it.”

New album in the works

For the past five years, Kirk has been touring heavily, performing shows as Cabaret Voltaire. But he’s taken a bit of a hiatus right now to complete a new Cabaret Voltaire release. The challenge has been converting the stage show into something that works as an album.

“I see it more like an art project, where I’m doing a performance. I’m not lit on stage. I use a large screen with three images on it like a split-screen thing, and it’s in total darkness as if you’re in a cinema. So there’s no element of performance whatsoever, it’s just the sound coming out of the speakers and the pictures. So I have about three hours of material that I need to refine and organize into an album. That’s where I’m at right now. The material is there, and it was designed for live performance, but obviously you need to have some more subtlety when you’re going to release it as an album.”

“Right now it’s all done with electronics but with live keyboards, and it’s almost like the early days where a lot of it was improvised and chance things happen. It’s not all pre-programmed. I don’t use any computers when I play live. I don’t use a laptop or anything like that.”

Kirk is pleased with the work he’s been doing, and with the fact that Cabaret Voltaire shows no longer spark riots. Yet there are things he misses about the early days.

“The thing you miss is that I’m the only person on stage, so if things get a bit tricky you can’t look to the left or the right to see your bandmates for reassurance.”

The recent spate of live shows has come at the expense of new studio material, and once the new Cabaret Voltaire album is done he thinks he might return to some of his other musical projects as well.

“I used to put out maybe three or four albums a year back in the day,” he reflects. “But because I’m quite a lot older now, it’s not like I need to keep putting out so much music. If the urge and the ideas are there, then I’ll do it, but it’s nice to have a life as well.”

Studio work aside, he does intend to keep touring. “I’m a youngster!” he exclaims, noting that the acclaimed DJ and producer Giorgio Moroder is still on the road performing at the age of 79.

That said, it might be a while before North American audiences hear a Cabaret Voltaire show. Kirk has a flying phobia (this writer can relate) and hasn’t set foot in an airplane in nearly 20 years. The last time he flew to North America was for a show in Montreal in 2000. A crowd in Toronto recently tried to get him to come, he notes, and went so far as to find him a berth on a cargo vessel traveling by sea to Canada. But in the end, he balked at the idea of 11 days at sea (one way) to play a single show and declined. He doesn’t drive, either, and does his European touring by train.

“At least I can say I’ve got a very good carbon footprint,” he observes wryly.

At this, our discussion turns toward the climate crisis – he cites Greta Thunberg’s recent journey to the United Nations in New York by boat as an example that it’s possible to eschew flying. He has a lot of respect for Thunberg for living up to her principles in that way. In many ways, her actions reflect the same intense degree of individual integrity that Cabaret Voltaire sought to inculcate through their work – a radical autonomy grounded in a sense of broad social responsibility.

“Be true to yourself. Don’t worry about the rules,” Kirk sums up as the lessons he would impart from his musical career.

They’re fitting ideals for life, as well.