Unlike many New York stories, Lee Israel’s is entirely free of glittery romantic embellishments. In fact, her travails veer toward the opposite, mining the city for its ruthlessly alienating tendencies.

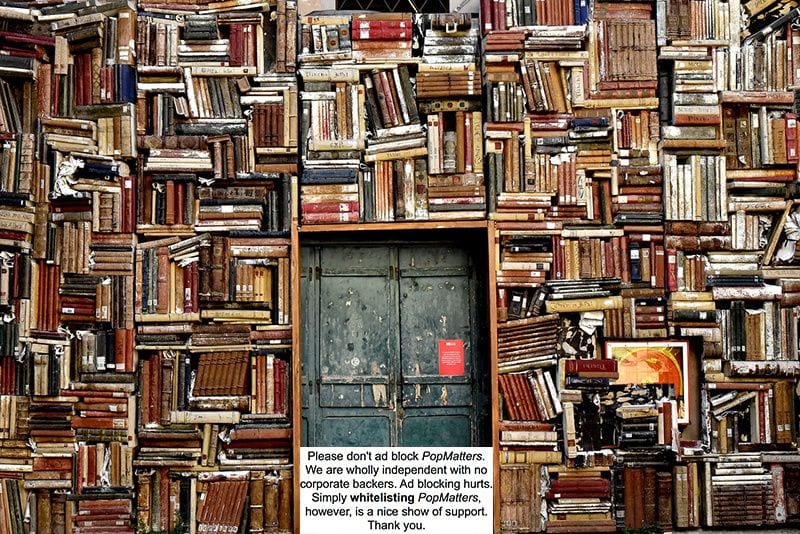

But Marielle Heller’s Can You Ever Forgive Me? isn’t exactly a traditionally “gritty” New York tale, either. Rather than gruff mafiosos or sly prostitutes, the film fixates on the rather niche world of bookselling; the drama is still there, but it’s mostly internal, navigating the complicated psyche of one woman shunned from the glamorous world of skyscrapers and determined to eke out a living on the ground floor.

It’s 1991 in New York, and Israel (Melissa McCarthy) is a struggling writer of celebrity biographies. Although once successful, her latest efforts fail to impress her agent (Saturday Night Live alum Jane Curtin, hinting at the film’s allegiance to caustic humor as well as drama), and her past books are being sold at a humiliating discount. Her personal life is equally depressing: she lives alone in a slovenly apartment on the Upper West Side, she can’t make the rent, and her beloved cat is sick. In other words, this is the story of a desperate woman. Can You Ever Forgive Me?‘s turn of events have a flair of tragedy, but the specificity with which Israel’s misery is wrought speaks to the true nature of the story. (The film’s title is taken from the real Lee Israel’s memoir, which accounts for her sudden life of literary crime.)

Her life of crime comes about in a moment of brief euphoria. Essentially blacklisted by her agent following a particularly combative meeting, Israel decides to forge letters by famous literary personalities and sell them for good money at bookstores around the city. She starts small, adding a droll postscript to a common letter of Dorothy Parker’s, and eventually turns the practice into a small-time operation. In the long run, it’s a failed operation before it even begins, but for the time being it gives her the means to support herself and, deeper down, a validation of her own cleverness and literary talent.

There’s a fair argument to be made that the only person Israel has to blame for her situation is herself, and in equal measure she’s the only one really able to fix it. But it’s not an easy task, and so it could just as well be said that desperate times call for desperate measures. She’s at least partially responsible for the mess she’s in, but nobody’s helping her, either. On the outside, Israel is gruff, cold and judgmental, refusing to project onto the world the kind of positivity she hopes for herself. It’s tempting to label her as unlikable, or even as an anti-hero, but more close to the truth might that she’s a tremendously complicated woman with a knack for self-sabotage. McCarthy, known largely for her vivacious brand of comedy, deserves huge credit for the character’s strange redeeming characteristics. We root for her even when the film doesn’t.

Some credit must also go to Heller and screenwriters Nicole Holofcener and Jeff Whitty, who coat the film in an empathy that grounds the narrative even at its most dour. The tight walk that is a movie’s emotional arc is especially noteworthy in Can You Ever Forgive Me? Its particular strength isn’t that it hits exceptionally towering highs or morbid lows, but that it maintains an intensely rewarding double act of pessimism and hope. Neither have to make room for the other; even in pursuit of an altogether abrasive story, they coexist with an admirable authenticity.

Much of the film’s lighter notes come from a character whose life is demonstrably worse than Israel’s but who’s nevertheless the only person remotely interested in helping her out. Jack Hock (an enchanting Richard E. Grant), a 50-something gay man who may or may not be homeless, is Israel’s only long-term human friend in the film, and in many ways acts as her perfect foil. He’s jovial and upbeat, and scarcely without a slick line or two to charm his way through the dregs of life. His official role is as Israel’s accomplice in literary forgery, but in more practical terms he acts as a tonic to Israel’s deep bitterness. They wallow differently, but are happier wallowing together.

There’s also Anna Miller (Dolly Wells), a bookshop owner whom Israel sells to and reluctantly develops feelings for. Homosexuality is a large part of Can You Ever Forgive Me?, but mostly just as another means of otherness instead of as any sort of grander statement. Being gay isn’t noticeably central to Israel’s personality, but it’s undeniably a contributing factor to her jaded self-alienation. With Hock, AIDS makes its appearance, but the matter-of-factness with which it’s presented is more heartbreaking than it is empowering.

In sneaky ways, though, the film works as a rallying cry for the dejected. Even if Israel isn’t exactly proud to be a criminal, she’s definitely proud of her writing, which routinely and her work reliably passes that of those she impersonates. There’s a satisfyingly rebellious edge to her trickery and the ways it raises a middle finger to the corporate literary establishment. On the other hand, though, is the debatably treasonous act of embellishing the works of dead authors, and thus, pieces of history.

As in Heller’s terrific last film, Diary of a Teenage Girl (2015), the characters here are allowed to make good and bad choices without being subjected to a final moral judgment. (There are traces of this in Holofcener’s work, as well). What’s more interesting than judgment, perhaps, is the human contradictions that make up Israel and, likely, us as viewers.

Can You Ever Forgive Me?‘s sprawl of urban loneliness is recognizable to anyone who’s ever lived in a big city, and in places so overcrowded with people and their ruthless ambitions, nuanced moralities must often follow suit. Israel spent a good part of her adult life, in both her biographies and her forgeries, tending to and hiding behind the cult of personality that surrounded artists like Parker, Noel Coward and Fanny Brice. That her own personality did nothing but alienate her is a potent bit of irony.