Did you know that Canada Day in Canada is actually Memorial Day in Newfoundland? It was the island’s ‘Remembrance Day’ before we joined Canada, since it commemorated a particularly bloody WWI battle that hundreds of Newfoundlanders were killed in. The odd result of this is that July 1st is both Memorial Day and Canada Day here. The flags fly half-mast in the morning and there are solemn wreath-laying ceremonies and sad tributes; then at noon the flags are hoisted back up and by evening there’s barbecues and fireworks going off. It’s like going through all of the feels in a single day.

Speaking of feels, looking for a good identity-confirming comic — or five — to enjoy over the holiday week?

Sure, you can dig out your old Captain Canuck issues. And if you’re lucky you might even have some Captain Canada and Captain Newfoundland comics lying around. But more than likely you won’t. It’s probably to Canada’s credit that it’s never produced a best-selling superhero like Captain America.

When Canadian philosopher George Grant wrote his seminal book-length essay Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism in 1965, he was lamenting the loss of a distinctly Canadian identity in the realm of economics (the acceptance of neoliberal corporate capitalism) and military policy (the acceptance of American nuclear bombs). But he also acknowledged the role of popular culture in this process, presaging cuts to the CBC and the incursion of American media (even back then).

Still, there are plenty of examples of comics and graphic novels that take pains to express, interrogate or otherwise engage with Canadian identity in surprising, innovative and useful ways. From sci-fi adventures to Indigenous and working-class histories, here are five comics worth checking out as you break out the BBQ and a two-four on the Canada Day holiday.

And the first one’s not even by a Canadian.

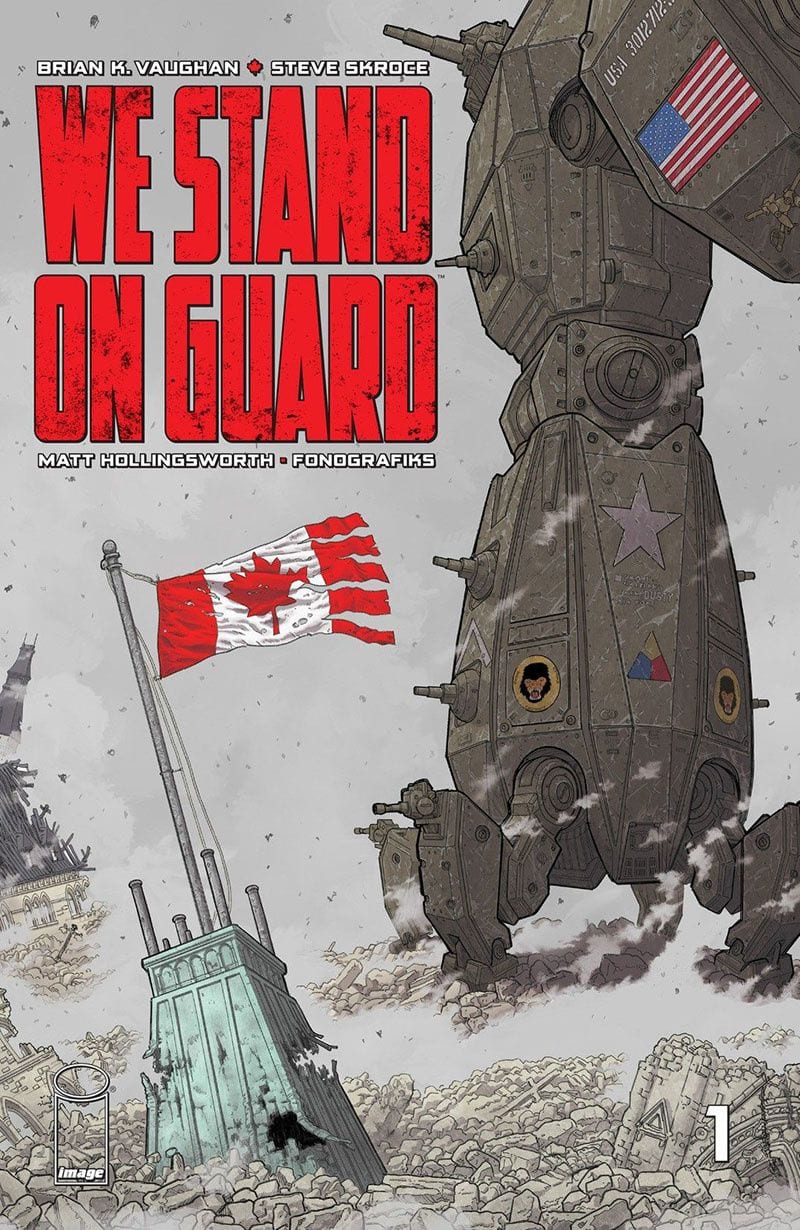

We Stand on Guard, by Brian K. Vaughan and Steve Skroce (Image Comics, 2017)

We Stand On Guard is a too-plausible-for-comfort sci-fi tale written by Brian K. Vaughan (Saga, Lost, Paper Girls, Y: The Last Man) and illustrated by Steve Skroce, about a futuristic war between Canada and the United States which succeeds in suspending the reader’s disbelief just a little too easily. In the year 2112, so this story goes, the US invades and occupies Canada. The US claims it’s in response to a terrorist attack on the White House; the more plausible theory is that an America ravaged by climate change has decided it needs Canada’s water resources in order to survive.

The rollicking adventure tale is centred on Amber, a young woman who grows up in the ruins of the American occupation and eventually encounters a Canadian resistance group operating in the far north, where American supremacy is still tenuous. The ‘Two-Four’, as they call themselves – “Since most of these dummies know more about drinking than fighting,” quips Qabanni, a former Canadian Tire employee – is composed of a smorgasbord of Canadian identity: an Indigenous Cree, a Francophone comedian, a gay Nova Scotian, a granddaughter of Syrian refugees, and more, all led by a former Regina chief of police. After getting their hands on a powerful piece of American military tech, the group concocts an unlikely plan for a strike on the Americans that just might drive them out of the country once and for all.

We Stand on Guard is a fun read, situated on the adventure sci-fi end of the spectrum. It’s beautifully illustrated in full-colour: lots of big military mecha and graphic explosions punctuate the whimsical text. It’s laden with in-jokes and cultural references—there’s a running argument about the origin of Superman; bits and pieces of Canadian art and literary references worked subtly into the background; and the Francophone (whose speech bubbles are entirely in untranslated French) makes hilarious witticisms about separatism.

But there’s an authentic, well-intentioned edge to the whimsy, which reflects the positive side of an identity politics that in this day and age is so often used to divide. In Vaughan’s comic, it’s used to unite instead. The granddaughter of Syrian refugees and the Indigenous Cree trade good-humoured banter about whose land “this country” really is and whose people experienced greater oppression (and who gets first dibs on a suicide mission against US troops). Indeed, while history suggests that partisans and resistance groups tend more often than not to gravitate toward xenophobia and racism, the strength of the Canadian resistance imagined by Vaughan lies in its diversity. He manages to work everyone in: Anglophones and Francophones; settlers, Indigenous and recent immigrants; gay and straight; virtually every region is represented as well. Vaughan’s occupied Canada is richly imagined, and makes full use of the country’s expansive geography. Prince Edward Island has been turned into a penal colony; Newfoundland’s pirates make life hell for the occupation; and the final battle with the Americans takes place at Great Slave Lake. Even Radio Free CBC makes an appearance.

There’s a lot of untapped potential in the comic, which could easily be exploited for future spin-offs if Vaughan and Skroce chose. Some characters have ambiguous pasts that are only partially explained, and it’s unclear right to the end who exactly was responsible for the White House bombing that purportedly led to the US invasion (US false flag attack? Or Canadian pre-emptive strike?). The psychology of life in an American-occupied Canada is never really explored (most of the action follows guerrilla-style resistance in the North, leaving one wondering how urban southern Canadians are coping). There’s a hint at the extent of collaboration between some Canadians and their occupiers, but it’s left largely unexplored. The conclusion itself has the air of being hastily conceived, with questionable consequences. Still, the comic was designed to be a bit of fun (when Vaughan’s Canadian-born wife took an American citizenship oath requiring her to take up arms against her birthplace if required, the creative wheels started turning). And it certainly achieves that. It’s funny, action-packed, and full of the characteristically suave pith and wit that readers have come to expect from Vaughan’s characters.

Yet it provokes unsettling questions; the veil of fantasy is a bit too thin for comfort. The comic is loosely based on contingency plans both countries actually developed in the early 20th century in the event they wound up at war with each other. And there have already been environmental and trade tiffs over water between Canada and the US (as far back as the ’50s the US was conceiving plans for nuking Canada’s North in order to supply water to its thirsty southern states). No shortage of recent and ongoing military conflicts around the world have been sparked over access to water resources, a state of affairs which is only going to worsen as the effects of climate change deepen. In an era when the US President has shown a disturbing propensity for trying to pick fights with his Canadian counterpart (and over more than just eyebrow fashion), nervous readers might indeed be left wondering: what exactly would happen if things went down this path?

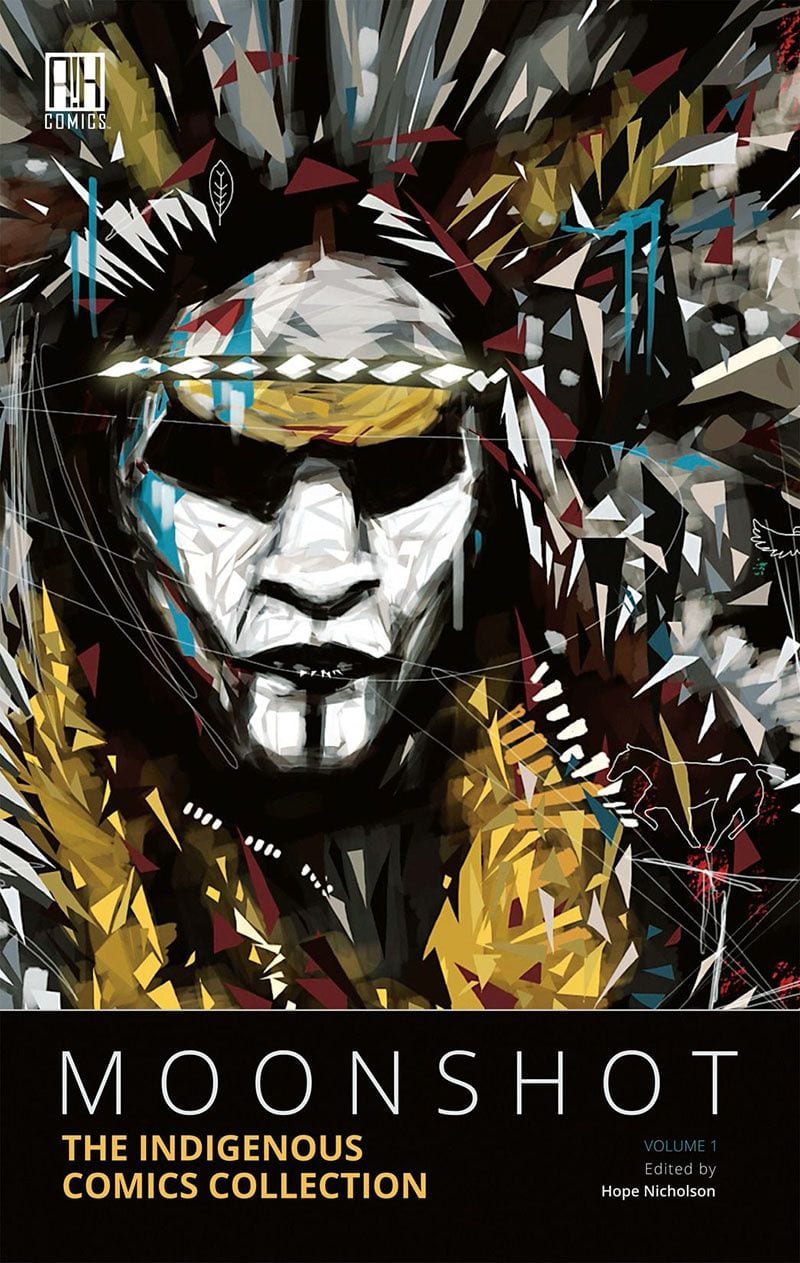

Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection, edited by Hope Nicholson (Alternate History Comics, 2016)

Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection is the first of three Indigenous-themed books in this list. It’s not exclusively Canadian, but spans the breadth of North America, achieving an equitable balance of authors, illustrators and stories from all across Canada and the US. Edited by Hope Nicholson, each story pairs a different eclectic duo of Indigenous writer and illustrator, spanning between them most parts of the two countries and a broad range of Indigenous groups: Metis, Inuit, Dene, Anishnaabe, Cree, Mi’kmaq, Haida, Sioux, and others.

Visually, the book is stunning, and worth picking up for the unbelievable quality of the art alone. Illustrators incorporate a broad array of styles: from Dave McKean-esque, early Sandman-style collage art, Euro-comics style bandes dessinées, Heavy Metal-like sci-fi/fantasy visuals, abstract shapes and colours, large water-colours, and more. There’s an immense variety of art in this collection, all of it full-colour and all of it perfectly splendid.

The storytelling is impressive as well. Some of it draws on traditional stories and myths, while much of it reimagines these stories: either in fantasy-style comics telling or futuristic, sci-fi iterations. The sci-fi stories are richly imagined, offering reminders of how archetypal Indigenous themes can be transposed onto futuristic and otherworldly settings. Likewise, myths from a variety of Indigenous cultures are retold as adventure, fantasy, superhero or contemporary tales, conveying a fundamental message that Indigenous storytelling is not a static practice involving the recital of a set historical repertoire, but is a living, breathing process of perceiving, understanding and communicating the world in Indigenous ways.

Nicholson reminds readers of this in the introduction: “There is no single, homogeneous native identity,” she writes, explaining that the stories in the collection were chosen because they’re ones that are “uncommonly told to help break down ideas of what native spirituality and culture ‘should be’.”

Thinking that science fiction and tales of extraterrestrial contact are the literary and creative product of European or settler cultures is a common mistake, Nicholson writes; those ideas and imaginings were present in many Indigenous cultures both before and after colonization. This is why the sci-fi stories are so powerful, incorporating as they do Indigenous motifs, themes and background elements. There are also, of course, darkly imaginative fantasies and mythic tales, including a couple of pieces of prose storytelling set to gorgeous art.

A second volume in the series was published in 2017, featuring additional writers and artists (including celebrated Inuk throat singer Tanya Tagaq). The expansive range of pieces and the superbly creative interactions of artists and writers in these stories makes this a collection that deserves far wider readership than it’s probably received. It’s important for all the social and political reasons for which it is important to showcase Indigenous writing and art in a settler culture that continues to ignore or downplay it, of course, but also simply because it’s one of the best collections of fantasy and sci-fi short stories to emerge in comics form in recent years.

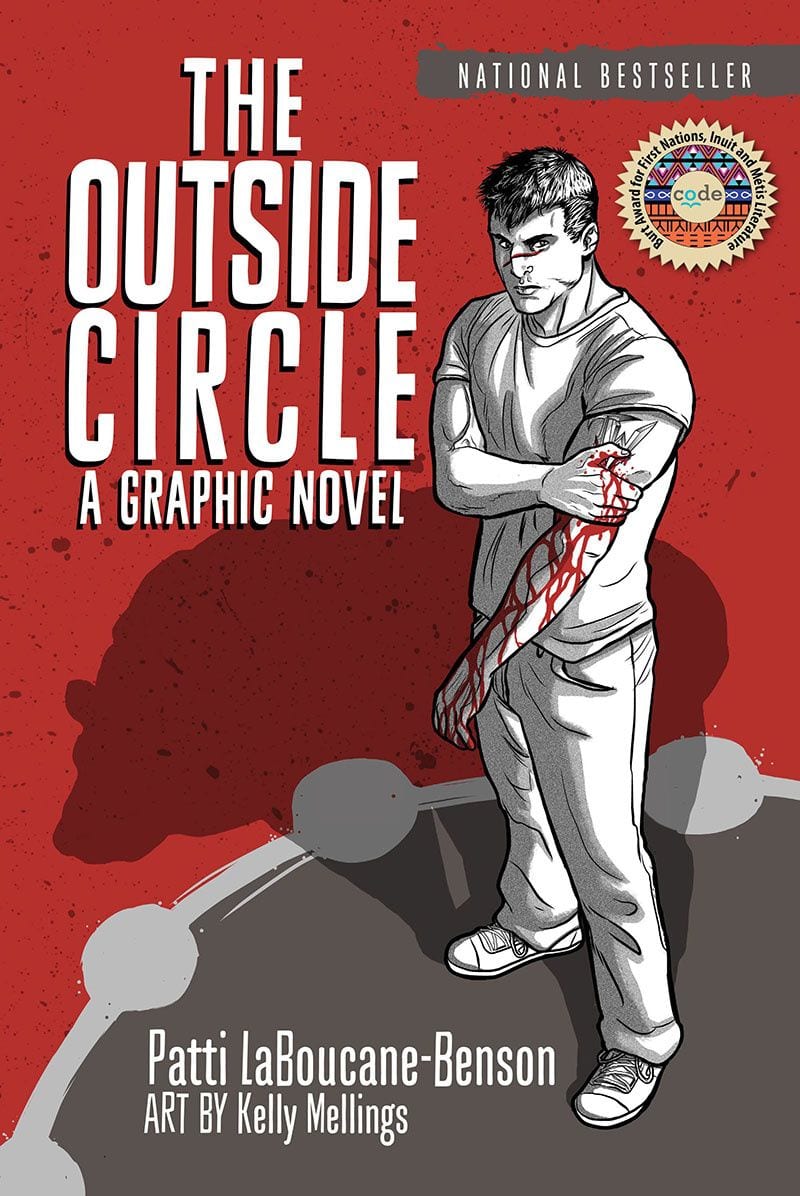

The Outside Circle by Patti LaBoucane-Benson and Kelly Mellings (House of Anansi Press, 2015)

The Outside Circle is an outstanding example of how a comic can be educational, inspiring, and yet truthful to the dark realities of Canada’s colonial heritage. It tells the fictional story of Pete Carver, a young Indigenous man in Alberta who’s become entrapped in a violent criminal street gang. After shooting his mother’s abusive boyfriend in self-defense, he winds up in jail, where an Indigenous Elder who works with the prison system introduces him to a series of programs grounded in Indigenous healing and rehabilitation practices. He gradually learns more about his cultural heritage as well as his own family history, and struggles to break free of the gang connections which have dominated his life thus far, and to become a supportive caregiver for his younger brother and daughter.

The book was written by Patti LaBoucane-Benson, a Metis woman who worked with the Native Counselling Services of Alberta and also conducted doctoral research on historical trauma healing programs for Indigenous offenders in the prison system. The book draws on much of this research—on the ‘In Search of Your Warrior’ program particularly, which is one that LaBoucane-Benson was involved in developing and implementing. Yet the book manages to avoid sounding either preachy or textbook-like.

At the same time it manages to be highly educational, embedding that history in a plausible dramatic narrative. The authors made a good narrative decision in depicting Pete’s violent gang lifestyle—one which appears superficially to adhere to many racist stereotypes and myths about Indigenous criminality and addictions—before proceeding to deconstruct the historical legacy and social conditions that have steered him toward his current hapless situation; the reader finds herself experiencing together with the protagonist the same dawning realization about the very clear and destructive impacts of colonialism on Indigenous youth like Pete.

LaBoucane-Benson’s insightful storytelling achieves a masterful synthesis with illustrator Kelly Mellings‘ stunningly beautiful artwork. There is a striking full-page image, for instance, where Pete’s tribal gang tattoo morphs into a timeline of the key historical events in the settler state’s engagement with Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Soon after, when the Alberta government is assuming guardianship of Pete’s younger brother Joey, there’s another image which someone reading quickly might overlook: the text of the supposed guardianship document is actually a brief history of the Canadian state’s many shameful methods of tearing Indigenous children away from their families, and in particular the history of residential schools. It’s elements like this that elevate the book above being just another comic with a message: it achieves a superior literary and artistic quality which renders its message even more powerful.

Residential schools form a key and recurring element of the book’s narrative. From the 1840s onward the Canadian state embarked on a cruel policy of forcibly removing Indigenous children from their families and communities and imprisoning them in ‘residential schools’ in an effort to assimilate them. In the residential schools they were forcibly Christianized, forced under threat of violence to abandon their cultural practices, bullied, mentally tortured, sexually abused, exposed to disease and brutal weather or working conditions, beaten and killed (the residential school system, like Canada’s broader ‘reserve’ program, was studied by white South African policymakers in the early 20th century and influenced the development of that country’s equally horrific system of apartheid).

As Pete gradually learns about his own family history, and the histories of his fellow incarcerated program participants, it becomes glaringly apparent how the individual, family and community traumas resulting from the residential school system have shaped the multi-generational experience of violence, trauma and mental health crises for people like Pete. While the Canadian government systematically expropriated the wealth (land, resources, labour) of Indigenous communities, miring them in poverty and often relocating them onto dangerous, remote or barren lands, it also sought to remove the final vestiges of Indigenous solidarity and resilience by literally tearing apart those communities and the families of which they were comprised. From the Bagot Commission of the 1840s to the ‘Sixties Scoop‘ of the previous century, the Canadian state’s policies of systematic genocide against Indigenous peoples have been thinly disguised under a variety of legislative and legal nomenclatures; The Outside Circle does a masterful job of exposing the brutal motives and consequences of these policies and illustrating their ongoing impact on Indigenous communities and individuals today.

As much as The Outside Circle depicts a bleak and ongoing part of Canada’s colonial history and identity, it’s also a story of hope, and provides a stirring example of the practices and traditions which offer a way out of this cycle. It’s an emotional tale that will bring tears to every reader’s eye, but also hopefully some idea of what needs to change to allow the country’s people to move forward together and achieve reconciliation.

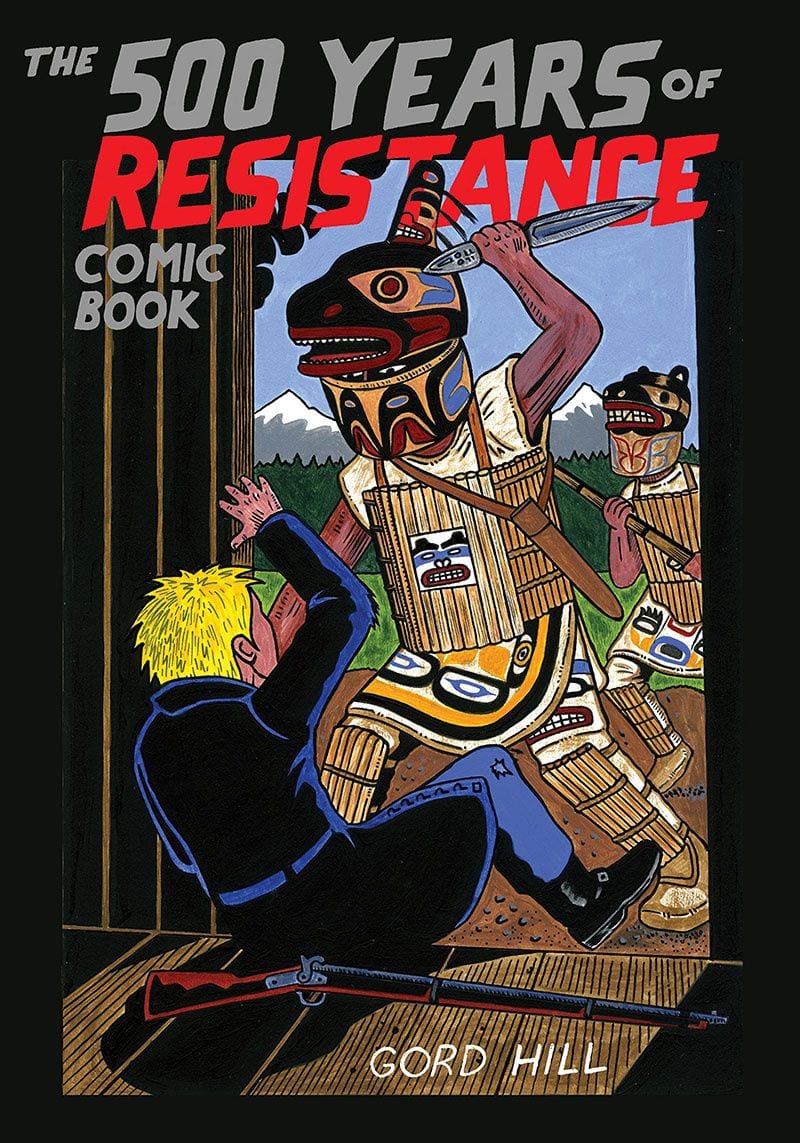

The 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book by Gord Hill (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2010)

Like Moonshot, Gord Hill’s 500 Years of Resistance Comic Book from Arsenal Pulp Press doesn’t limit itself to Canada, but spans Indigenous resistance the length and breadth of the Americas. But that in itself is an appropriate reminder of the arbitrary borders and divisions established by European settler colonial states as they invaded and expropriated Indigenous lands over the past 500 years.

The comic, originally published in 2010, conveys its message in simple and often graphic detail. Following a lengthier section on the initial European contact and invasion, it consists mostly of one to two page spreads on varied instances of Indigenous resistance to settler colonialism, ranging from the Inca Tupac Amaru’s insurgency in what is now Peru in the 1780s, to the American Indian Movement’s stand-off with US settler colonial forces at Wounded Knee in 1973. Hill explores several lesser known cases of resistance in between: the Mapuche of southern Chile; the 1680 Pueblo revolt in what is now the Southwest US; the 1763 uprising of the Ottawa war chief Pontiac; the Florida Seminole wars; the resistance of the Apache and the Plains Nations (the latter of which included the more well-known Battle of Little Bighorn); the various resistance struggles of the peoples of the Pacific Northwest (in what is now British Columbia and Alaska); and the rise of the American Indian Movement. He also considers various less overtly confrontational (yet often equally violent in outcome) assimilationist strategies (residential schools, reserves, Christian missions) employed by settler colonial governments, and the ways in which Indigenous peoples resisted these as well.

Hill’s expansive geographical backdrop—the entirety of North and South America—is ambitious but a useful reminder of the scale of the continent’s Indigenous genocide. The final set of chapters in particular are a reminder that while the settler colonial governments of Mexico, the United States and Canada squabble even today with each other over trade and borders, the rightful Indigenous stewards of their countries are the ones paying the most devastating price of settler state colonialism. From the Zapatista uprising in Mexico (directly linked to the signing of the original Canada-Mexico-US free trade agreement in 1994), to the AIM resistance at Wounded Knee in the United States, to the Canadian state’s confrontations with Indigenous peoples at Oka, Quebec (1990), Ts’Peten (Gustafsen Lake), British Columbia (1995) and Aazhoodena (Ipperwash/Stoney Point Ontario, 1995), the book offers an important reminder of the a stark contrast between the geopolitical priorities of US President Trump, Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau and other white settler leaders of the Americas, and the struggle of the continent’s Indigenous peoples to survive and rebuild communities and traditions in the face of ongoing state-supported violence.

500 Years of Resistance is a short book and a quick (if brutal) read; Hill’s approach is to provide a broad survey, not in-depth research. Having been published in 2010, the book omits the many more recent struggles, from the struggles against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock in the US and the Trans Mountain Pipeline in British Columbia, to the struggles of Indigenous peoples in Ontario (Six Nations Grand River/Caledonia), New Brunswick (Elsipogtog), Newfoundland and Labrador (Muskrat Falls), and elsewhere. Yet it remains an excellent introduction to the tremendous historical and ongoing legacy of resistance on the part of Indigenous peoples in Canada and elsewhere in the continent against the settler colonial regimes that continue to oppress and exploit.

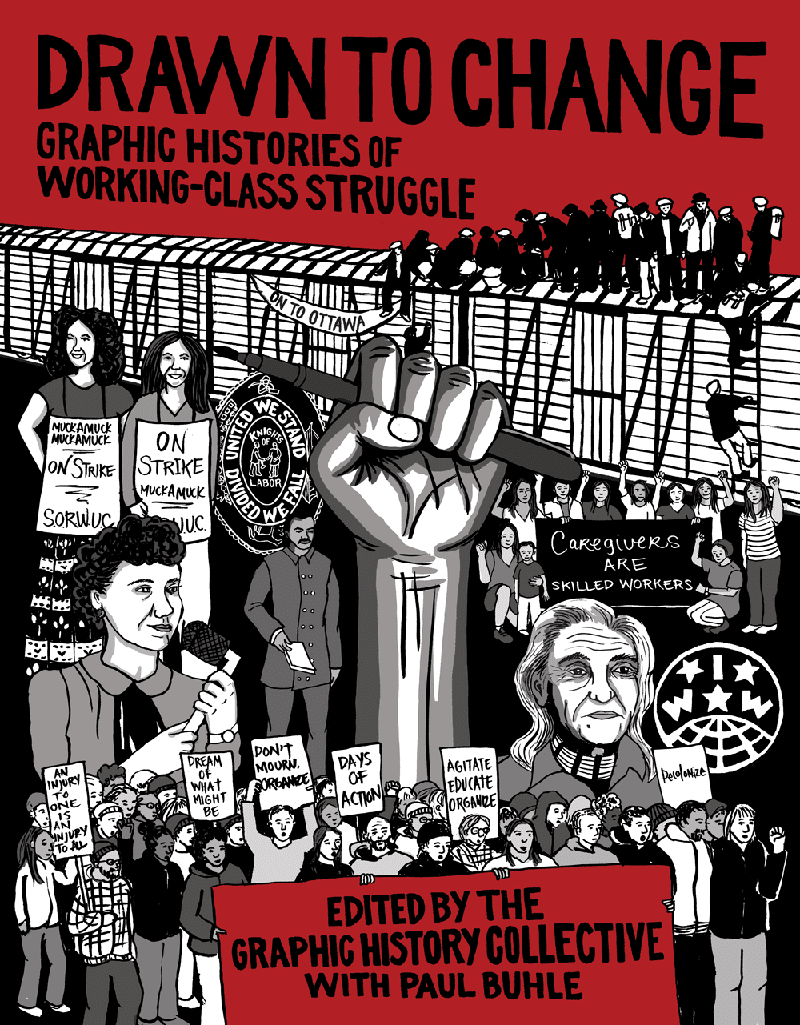

Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working-Class Struggle, by the Graphic History Collective (Between the Lines, 2016)

The Canada-based Graphic History Collective was founded in 2008 and describes itself as “a group of activists, artists, writers, and researchers passionate about comics, history and social change” that produces “alternative histories – people’s histories – in an accessible format to help people understand the historical roots of contemporary social issues.”

To date, it’s produced two print publications: the short 2012 comic May Day: A Graphic History of Protest and the much larger and more substantive Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working-Class Struggle, an anthology published in 2016. It hosts a strong online presence as well, showcasing several web comics about protest and struggle from all over the world — Greece, Ireland, Australia, and more.

Paul Buhle, in his preface to Drawn to Change, enthusiastically calls it “proletarian art… comics about workers by workers.” Well maybe, but the initiative actually started as a federally funded project spearheaded by a group of academics and historians affiliated with the Canadian Committee on Labour History. The Collective which resulted has continued rolling on its own, though, and the work it has produced offers an important example of the use of graphic narrative to teach people’s history.

Drawn to Change originated as an online collection of comics illustrating “the various ways in which people from a diversity of backgrounds historically struggled for social change.” From the comics that were submitted and posted to the website, nine comics focusing on aspects of Canadian labour history were selected for the print volume, which also includes an excellent short overview of the history of ‘activist comics’, with attention to the Canadian context.

Visually the comics draw on a range of styles but nothing so grandiose as the magnificent art contained in Moonshot. The comics in this volume are black-and-white, and range from cartoon pencil illustrations to stylized, semi-realistic pen-and-ink. More restrained than the other volumes in this list, they’re impressive nonetheless; the illustrations weren’t simply dashed off, but each story is complemented with distinct, thoughtful and well-realized artistic styles. Several of the chapters consist largely of narrative bubbles over artistic panels, but dialogue and action emerges in a few. Some of the pieces are highly stylized and adopt more abstract approaches to combining text and art. The art is eminently satisfying, and offers a worthy backdrop to the well-researched and thought-provoking content.

The stories included in the collection include biographical pieces (on Quebecoise feminist and labour organizer Madeleine Parent, and Bill Williamson, a communist organizer, “hobo”, Spanish Civil War veteran and photographer); chapters exploring specific labour struggles (the 1935 Corbin Miners’ Strike in British Columbia, and the ‘Battle of Ballantyne Pier’ between striking waterfront workers and Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Depression-era Vancouver); overviews of seminal moments in labour organizing (the history of the Knights of Labor in the late 19th century and the Service, Office and Retail Workers’ Union of Canada – SORWUC, a feminist union which organized women workers in the ’70s and ’80s); Indigenous struggles (including an innovative chapter on Indigenous labour struggles, “Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land: Indigenous Labour on Burrard Inlet”) and the struggles of immigrant workers (“Kwentong Bayan: Labour of Love” explores the experience of Filipina live-in caregivers).

Many of the chapters deploy innovative historiographical efforts to remain true and authentic to the voices of the workers whose stories they tell. The chapter on Williamson, for instance, is told in first-person in his own words, and “Working on the Water” incorporates transcripts of oral interviews given by the Indigenous labourers whose stories it relates. Indeed, the book makes a determined effort to maintain an intersectional lens, considering how the varied struggles impacted not only their direct subjects but also the Indigenous, racialized, gendered and other communities of workers in the cities and provinces where they take place.

Drawn to Change is a tremendous example not only of working class struggle and idealism, but also of the potential of graphic narratives for depicting and communicating people’s histories. The chapters are accessible, but also intelligent; each chapter is introduced and critiqued by academics in the field and engages with serious social and political debates; ones which resonate today as much as they did a century or more ago.

The book’s penultimate chapter should strike a particular chord. “Days of Action: The Character of Class Struggle in 1990s Ontario” covers the struggle against Conservative premier Mike Harris in the late ’90s. Harris instituted a wave of neoconservative austerity measures the province has still not recovered from. The June 7th election of a new provincial Conservative government in Ontario under Premier Doug Ford looks set to reframe the Harris era as a picnic by comparison, and the lessons and tactics illustrated in “Days of Action” will undoubtedly be dusted off before long by a new generation of Ontario activists.

Oh Canada… plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. But learning one’s history is the first step toward not repeating it, and Drawn to Change—like many of the other books on this list—offers an excellent, important and enjoyable way of putting that tenet into practice.