Carol Hall was the composer whose musical, The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas, became a worldwide success, leading to a film adaptation and a sequel. She also contributed to Free to Be You… And Me, Marlo Thomas’s popular children’s project, and Sesame Street, and her songs were recorded by a host of stars, including Barbra Streisand, Tony Bennett, Maureen McGovern, Rupaul, Chita Rivera and Olivia Newton-John. Less well-known, however, were the two albums she made as a singer/songwriter, issued by Elektra Records in the early ’70s. Hall died in late 2018. I had the privilege of conducting a final interview with her earlier that year, during which we focussed on her early ’70s singer/songwriter period.

* * *

To musos and aficionados of musical theatre, Carol Hall’s immense talent is well-known and highly respected. Within that group of admirers is a sub-group; the ones who knew and loved the singer/songwriter albums she made for Elektra Records, long before she found wider fame with The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. Hall’s music had the un-showy, literary sophistication of her label-mate, the late, similarly underrated David Ackles. She had an ear, not just for melodies that possessed a singular pulchritude, but also for profound turns of phrase and, judging by a song she recorded in her later years (“My Circle of Friends”), it never deserted her.

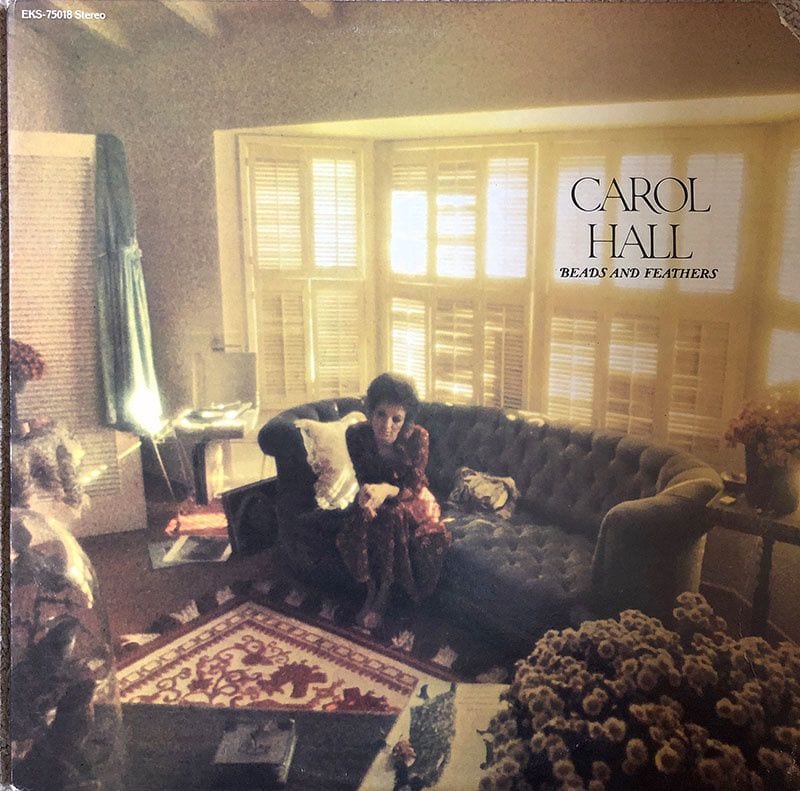

There used to be a haphazard record shop in Soho, London, with the refreshingly un-aspirational name of Cheapo Cheapo. It was two storeys of chaos but if you were prepared to persevere, it was possible to find jewels among the junk. On an otherwise unremarkable day in 1999, I found an album called Beads and Feathers and, despite its rather jaundiced, murky cover art, I took it home. What emerged was an embarrassment of riches; 11 remarkable songs, witty and with a charmingly bookish sensibility, characterised by pathos that never descend into mawkishness.

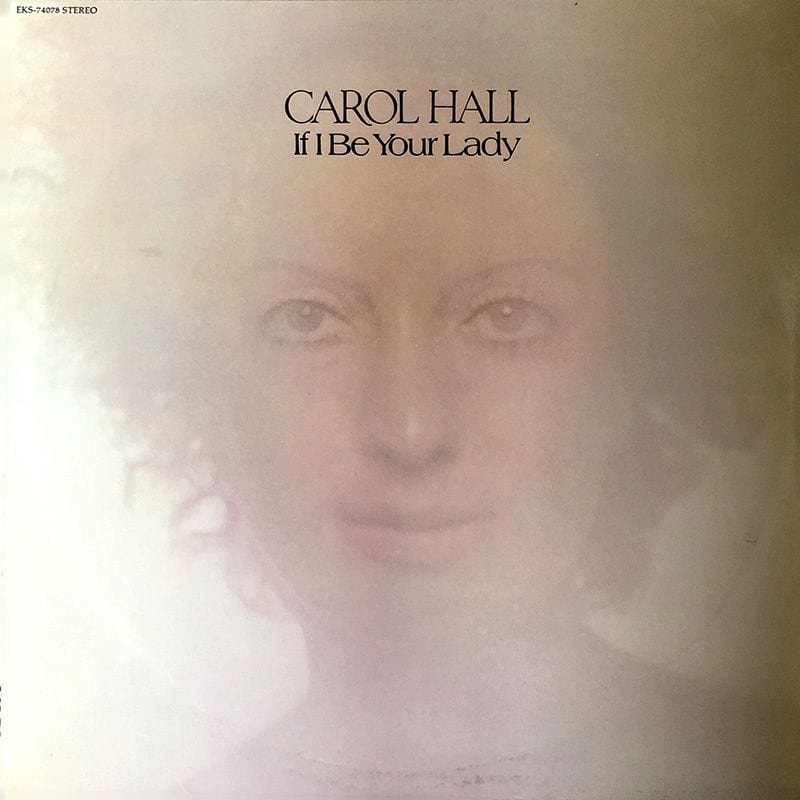

This was a woman with world-class songwriting chops. Hall’s voice, not conventionally pretty in the manner of, say, Judy Collins, but a great, slightly weathered, actor’s voice, was the perfect vehicle for conveying the emotions in her songs, each of which depicted characters (sometimes Hall herself, sometimes fictional, sometimes other people in her life) caught up in jubilant, sad, despairing or mixed circumstances. These ranged from divorce (“Hard Times Lovin'”) to early sexual experiences (“Carnival Man”), to fractured friendship groups (“Hello My Old Friend”) to the physical decline of elderly relations (“Nana”). Beads and Feathers had been preceded by Hall’s debut, If I Be Your Lady (Elektra, 1971), another exceptional work, with Hall’s songs given more elaborate, ornamental arrangements. Although for my money it’s very marginally inferior to her second album, If I Be Your Lady contained Hall’s first hit as a songwriter, “Jenny Rebecca”, recorded by Barbra Streisand in 1965 and then a long list of other vocalists, including Olivia Newton-John.

Although much of Hall’s professional life took place in New York, she came from Texas. Her grandparents were West Texas pioneers. Her mother, Josephine Grisham Hall, was a classical musician (piano/violin) and music teacher. Her father, Elbert Emmit Hall, ran Hall’s Music Store in Abilene, Texas, before becoming an insurance salesman (he would eventually become Mayor of Abilene in the early 1980s). When Hall’s parents divorced, she and her mother moved to Dallas, where Hall attended Hockaday School, before graduating from Highland Park High. Hall studied classical piano. “It then came time to go to college,” says Hall, “and unfortunately my mother picked one out for me: a nice Southern institution for bright young women named Sweetbriar College, in Lynchburg.” Hall spent two years at Sweetbriar. “Eventually I transferred to and graduated from Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, New York, in 1957.”

A long-standing friend of the Hall family was Englishman, Don Law, head of Columbia Records’ country music division for much of the 1950s and ’60s and a talent scout who stayed abreast of musical goings on in Nashville and Memphis. “Don was one of the most important and successful producers in country music. He recorded Carl Smith, Lefty Frizzell, Ray Price, Little Jimmy Dickens, Johnny Horton, and Johnny Cash, to name a few. Prior to that, he’d been instrumental in bringing to Columbia Bob Wills, Al Dexter and blues legend Robert Johnson.” Thanks to this friendship, the young Hall got to sit in on C&W recording sessions, burnishing her fondness for the genre. “In addition, I became enamoured of writers such as Cole Porter, Yip Haburg and the extraordinary Jacques Brel.” Years later, if anyone could be said to have bridged the stylistic space between country music and Brel it would, on the strength of her two albums, have been Hall herself.

Hall couldn’t have hoped for a better grounding in musical theater than that which she received under Lehman Engel, the New York-born composer and conductor whose BMI workshop for composers and librettists she joined after graduating from Sarah Lawrence. “I became even more prolific a theater writer. I also joined with occasional book writers and wrote songs for their works.” While she contributed to a series of Off-Off-Broadway productions, Hall’s songs began to find their way to prominent vocalists, including Ed Ames (“The Ballad of the Christmas Donkey”), Miriam Makeba (“Little Bird”) and Tony Bennett (“The Two Lonely People”). “Jenny Rebecca”, a lullaby for a newborn, was recorded by Mabel Mercer. “That opened the door for a mutual friend to submit it to Streisand and she recorded it on her My Name Is Barbra album.”

“Jenny Rebecca” would become one of Hall’s standards. “I wrote it simply as a baby gift for a close friend. That actually was the baby’s name. It was the first friend who had accomplished such an amazing miracle and it really made an impression.” Hall took an enterprising, DIY approach to promotion: “After I had written it, with all the brash innocence of youth, I sent it to Mabel Mercer. Well, I did what any sensible young writer would do; I looked her up in the New York phone book. And there she was! So I called her. And she answered the phone! I introduced myself and told her I had a few songs I thought she might like and to my surprise she directed me to send them to her. So, I did. A few days later, not having heard back from her, I picked up the phone and called her again. And she answered and I said, ‘Miss Mercer, what about my songs? I just want to know if you liked them or not.’ And with that beautiful mellow voice, she responded, ‘Yes, my dear, and I’m learning them right now’. And that’s how they got on her Town Hall Concert albums.”

“Jenny Rebecca” would go on to be wrapped in the voices of Olivia Newton-John, Neil Diamond, Bobby Gosh and many others. “I was particularly thrilled when Frederica Von Stade not only recorded and performed it, but named her daughter Jenny Rebecca as well.”

Through the ’60s, Hall was busier and busier. “I networked with people in the advertising world and began writing jingles for commercials as well.” As the decade came to an end, a new type of performer began to emerge; the singer/songwriter. Hall hadn’t regarded herself as one of them. She was a writer and composer, first and foremost. “I was signed to the William Morris Agency by a theater agent, Ginger Chodorov, whom I knew from the Sarah Lawrence days.”

Hall was focussed on one thing alone: building her musical theater career. Nevertheless, given the success of Laura Nyro, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, and Janis Ian, it was only a matter of time before someone spotted the fact that Hall could do what they did; accompany herself on the piano while singing her own songs. Even performers who’d started out as interpreters were getting in on the act; Judy Collins and Joan Baez began to fill out their albums with their own compositions. Although she was signed to a theatrical agent at William Morris, it wasn’t long before their record division noticed her, in the form of young agent, Scott Shukat, who effected a pivotal introduction. “He got me to Jac Holzman, legendary CEO and founder of Elektra Records. Jac fell in love with my songs and signed me to the label.”

Elektra, simultaneously masterminding Carly Simon’s career, was the perfect home for Hall, whose songs and singing were unusual and intelligent. The label was associated with quality, discernment and elevated taste and had issued several albums by David Ackles (whose musically and lyrically elaborate songs make him perhaps the closest thing to a male equivalent of Hall), Judy Collins, the Doors, and Love. Unfortunately, further down the line, they would make some crucial missteps in terms of how they presented Hall visually. Everything else, they got right. In 1971, the first fruit of Hall’s coupling with Elektra was issued. The quaintly named If I Be Your Lady featured a generous 13 Hall songs, including her calling card, “Jenny Rebecca”.

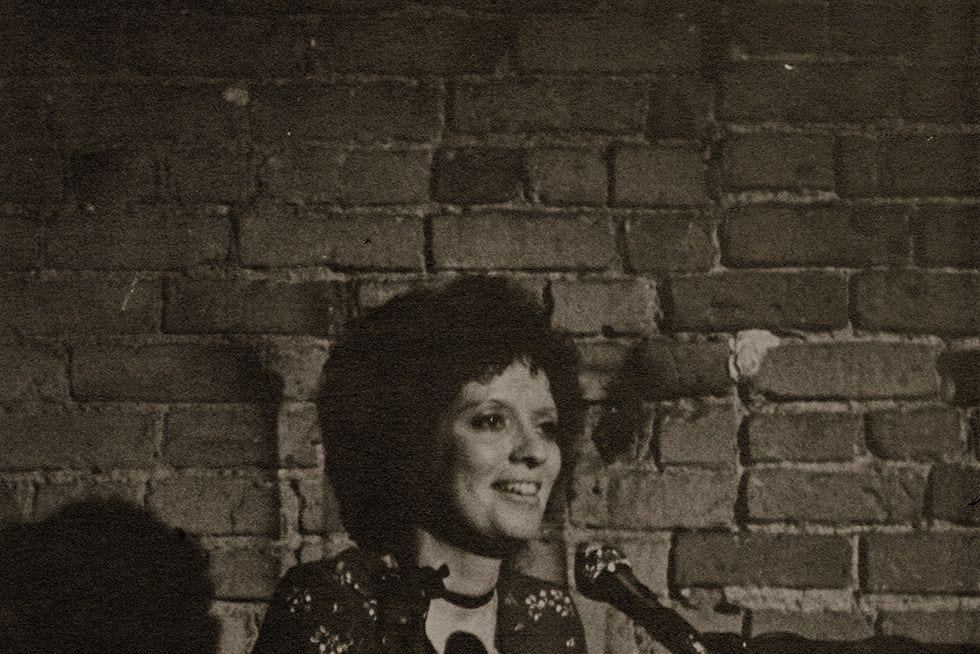

A requirement of almost all singer/songwriters was that they go out and perform in public, though not all relished the prospect. Singer/songwriter Margo Guryan had flat-out refused when Bell Records expected her to do it and, as a consequence, they withdrew promotion of her 1968 album, Take a Picture. “I was not performing at all,” says Hall. “Just before Elektra released If I Be Your Lady, William Morris began booking me as an opening act for other singers.” Hall was wracked with nerves; she enjoyed toiling as a writer, well outside the glare of the spotlight. “The first performer I opened for, much to my astonishment, was Kris Kristofferson at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village.” The pair clicked. Not long after, when Hall’s album was ready to go to the presses, Kristofferson wrote the following foreword/liner note, a shortened version of which was printed on If I Be Your Lady‘s shrink-wrap:

“Carol Hall is a beautiful surprise. One of the lucky experiences that comes along when you’re past expecting anything new under the sun. Like the first time ever hearing Joni Mitchell. Or James Taylor. Except that she’s not like anything I ever got excited about.

She is, in truth, one of the best writers I’ve ever heard. Her songs are beautiful and unmistakably her own, with the paradoxical unpredictability and haunting familiarity of real and creative imagination. They remind me of Robinson Jeffers’ poems. Some — like “Ain’t Love Easy” — sound like money in the bank; the others are just sauce for the soul. I’m grateful that they’re presented so tastefully in the arrangements of this album. God knows where it comes from, but she’s got it!

As a performer she is so damned right that it’s hard to believe this is her first album, or that the club date we shared at the Bitter End was her first paid appearance. She is more polished and technically correct than she deserves to be, but in spite of this she’ll move you. Emotionally. Which is where art’s at. P.S.- Billy Swan says to say how pretty she is.” [Billy Swan played bass with Kristofferson’s touring band]

The album, produced by Keith Holzman, more than lived up to the praise. It exhibited 13 shades of Hall’s writing talent; remarkably perceptive, prettily orchestrated songs about romantic nostalgia, social mores, and inter-personal entanglements, some of them wry (“Why Be Lonely”), others more earnest (“Let Me Be Lucky This Time”). Haunting, expertly constructed vignettes like “The Crooked Clock” and “Crazy Marinda” reflected Hall’s theater background. It’s worth noting Kristofferson’s reference to Hall being pretty, because this is where Elektra missed a trick. Even if they didn’t want to sell Hall as a Carly Simon-esque sex symbol, it would surely have been a good idea to make her look recognisable and engaging on the front cover, given that this was her first step into public life. Instead, despite the fact that Hall had an urbane, fashionable and charismatic look, they presented her as a fluffy, matronly blur.

The back cover, also blurry, did at least give the potential buyer some indication of a human being. But the crucial front cover, the first point of contact between Hall and her potential audience, was so ethereal as to almost not be there. To Hall, its gauzy blankness was a missed opportunity. “It didn’t help that Jac happened to sign Carly Simon at about the same time. By contrast, Carly’s first album cover was very sexual, to say the least. Her single, “That’s the Way I’ve Always Heard It Should Be” was in the charts and caused them to give her a second album very shortly thereafter and begin to promote her more strongly.”

Despite playing second fiddle to other acts at Elektra when it came to promotion, Hall kept playing live. “I opened for Waylon Jennings and even rock groups such as Sha Na Na. The most thrilling time was when I became the opening act for Don McLean (whom Scott also represented) just as his song “American Pie” connected. What a glorious writer – I learned a tremendous amount about performing and singing from him. He is a consummate musician, having studied at the foot of Pete Seeger. Early into it, I asked him about performing and he said, ‘Aren’t you listening to the audience? They don’t have to talk to you to communicate. They tell me what to do all the time, what song to sing next, what I did wrong, what I did right.’ I thought a lot about that. That’s when I began to enjoy performing.”

Although she’d long since relocated to New York, a Southern sensibility still informed some of Hall’s writing – linguistic rhythms and imagery that could only have occurred to someone with her geographical background. “There are gentle rhythms and cadences which exist in the Southern speech,” she agrees. “There’s also imagery which often emanates from rural living and other farm- or agricultural-related tasks, the land, an awareness of the natural world. Also, biblical references are a commonality in the community and unexpected juxtapositions of action and image. When I wrote the lyrics for a musical based on Truman Capote’s A Christmas Memory, I had to call upon that sensibility quite a bit, just as I did in The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. In Whorehouse, the Sheriff sings about Miss Mona, referring to her as “a good ol’ girl [who] ain’t the clingin’ kind.” In A Christmas Memory the narrator sings of an early November morning, “clouds hangin’ white as a sheet on the line,” and the lead character, Sook, laying content in a field, looks up and sings “I could leave the world with today in my eyes.”

Crazy Marinda

Elektra were keen to give Hall a second outing. Meanwhile, she was keeping the ball rolling with side-projects. “I was a single parent at the time, with a young son and daughter, and it certainly became a challenge to get them off to school and all that entailed, and to find the time to keep writing. I wrote a lot of commercials, just to pay the bills and keep things going. But being a parent came in handy when I was invited to write for Sesame Street, Big Blue Marble and other children’s projects.” Prominent among those was the multi-media (album, book) children’s entertainment project, Free to Be… You and Me (Bell Records, 1972), to which Hall contributed “Parents Are People”, “It’s All Right to Cry”, and “Glad to Have a Friend Like You”.

When it came time to prepare her second Elektra release in 1972, a conscious effort was made to give the audience something closer to the experience of Hall as a live entity, and to jettison the more elaborate, prettifying arrangements of the first album. “Beads and Feathers reflected what I’d learned from performing,” says Hall. It is an album that deserves all the accolades retrospectively afforded to David Ackles’s American Gothic. It was more assured than the debut and Hall’s singing was stronger. Her acting ability, the way her voice and phrasing added subtle layers of nuance and meaning to each line, was eerily good, the songs exceptional.

In contrast to the debut, the recordings had more rock-music heft, more immediacy, and a stronger sense of their author’s identity. “Those rock influences came from the extraordinary session musicians on the gig – percussionist Kenny Buttrey (who worked with Bob Dylan, Jimmy Buffett, Neil Young), David Briggs (one of an elite core of Nashville studio musicians known as “the Nashville Cats” and who worked with Elvis Presley for years), Norbert Putnam who, with Briggs opened Quadrafonic Studios, Wayne Perkins (worked with Eric Clapton, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Leon Russell and became lead guitarist on the Stones’ Black and Blue album), Eddie Hinton, Marlin Green, Billy Sanford. They all respected the material and did their best to create interesting support for it.”

Production shifted from Keith Holzman to Russ Miller, “because Elektra decided to produce in Nashville and give the album a stronger country sound,” explains Hall. “If I Be Your Lady was arranged by a very talented New York musician, David Horowitz, filled with strings and lush, interesting arrangements. Going to Nashville for Beads and Feathers meant a leaner sound, with Nashville musicians improvising a great deal and contributing a different feel to the songs (and being stoned a good deal of the time).” As before, Hall was an integral part of the arrangements, accompanying herself on piano.

Unfortunately, for the second time in a row, Elektra went for ‘dowdy’ with the visual presentation. The concept itself wasn’t faulty; taking a line of lyric from “Sunday Lady” (“She’s home, playin’ her records“), Hall is captured in a carpeted sitting room, a Dansette-type device to her right with albums scattered beneath. It’s the styling that’s problematic. The room is dingy, shrouded in brownish light. The shot is fuzzy, so it’s impossible to connect with Hall’s face, person to person. “Although we didn’t really do any recording in LA to speak of, the cover was staged and shot there,” recalls Hall. “Once again, the art director created this hazy, soft, melancholy, introspective, studio look with sunlight filtering in through mostly closed shutters, reflecting on a muted carpet.” Had they only thought to ask, they’d have discovered that Hall’s New York living room was bright and zesty, furnished with Moroccan rugs and Haitian artworks – the polar opposite of the album cover’s rather baleful, spinsterish styling.

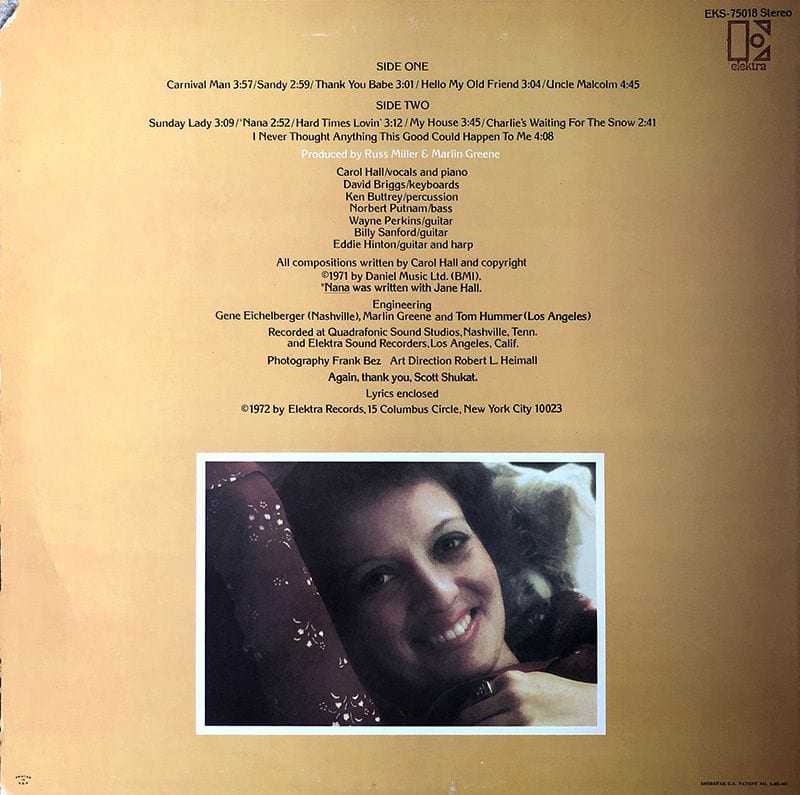

The back-cover was little better, with a tight head-shot of Hall that made her look slightly conservative. One interesting touch, however, was the double-fold insert with not only the lyrics but also atmospheric photographs of Hall’s forebears. Since the album’s songs included several family reminiscences, it was an apt touch. “That was my grandfather, driving one of the first cars in West Texas, my grandmother and the Whist Club of Toyah, Texas, plus various unknown cowboys with relatives,” she explains.

As before, design missteps aside, the most crucial aspect of the album, the music, was almost without flaw, and such flaws as were present were were the kind that added piquancy. “I act the “story-song” taking place,” says Hall, when I ask about her approach to vocals. “And that really emanates from the writing, which is, in many instances, depicting a person or character in a specific place, musing on the circumstances he or she finds himself in. I have always been a theater writer, which means that the answer to the question ‘which comes first: the music or the lyrics?’ is, actually, the character comes first – the person who is singing. In almost every song on Beads and Feathers, a person is caught up in an emotion because of events, and so the exercise becomes to act first, sing second. They’re like plays, only shorter and more formally structured.”

And her characters aren’t just caught up in one emotion; sometimes, they inhabit a dazzling array of feelings. On “Carnival Man”, a woman is in a reverie of sexual and romantic nostalgia. It’s an attention-grabbing way to open an album. “Sandy”, which follows, warms to the same theme. The narrator recalls losing her virginity to Sandy, a sensitive lover and poet whose presence in her life causes consternation between her parents, keen for her to choose someone sensible with prospects. “I recall performing “Sandy” at one of my earlier High School alumni weekends in Dallas and at least half a dozen men came up to me at one time or another during the evening, saying quietly “I was Sandy, right?” I subsequently placed the song in the score of a wonderful Off-Broadway musical I wrote called To Whom It May Concern.

“Hello My Old Friend” brings haunting regret, self-deception, and broken promises, as members of an old friendship group partially reunite, discovering that things haven’t panned out favourably for all of them and making half-hearted attempts to sound more caring than they really are. The song has a gripping awkwardness about it, with Hall’s lines delivered in strident outbursts and then soft murmurs of melody, perfectly capturing a group of people in denial about their own callousness and indifference towards each other. Hall is a consummate songwriter and every detail makes sense, including the superficially cheery 6/8 time signature reflecting the way the narrator tries to hide the truth beneath a friendly facade.

“Uncle Malcolm” is taken directly from Hall’s own life and details Hall’s return from New York to Texas to attend a funeral, suffering the opprobrium of gathered family members. “Yes, there indeed was an Uncle Malcolm (“Unkie”), and there were all the relatives exactly as I describe them. It was quite radical for me to go off to the city and make my way as a songwriter. I think most of my relatives didn’t really sit up and take notice until The Best Little Whorehouse… emerged. And I finally achieved the Seal of Approval when Dolly Parton made “Hard Candy Christmas” such a recognizable Country Western hit. In retrospect, I might have exhibited a bit too much self-pity in the construction of this song, but at the time I really didn’t know why I wasn’t instantly becoming a household name and, through the song, I was really examining the value systems inherent in my country relatives versus my city quest for fleeting fame and fortune.” Self-pity or not, Hall’s description of hard-hearted relations with ‘taut-rope faces’ and ‘hands that never touch’ (“they don’t think high of city folk/so we don’t talk too much“) set to bleakly dramatic music, brings the curtain down on Side One with arresting panache.

Of the songs on the second side, “Hard Times Lovin” ushers in sharp pain, icy silences and the beginnings of divorce. There’s a jaded tension to the music, with the rhythm, established from the beginning by Hall’s piano, once more being key to the overall feel of the song. One of the clever musical hooks is formed by the way the first lines of each verse are sung strictly one syllable to one note, but ending with a melismatic phrase (“Hard-eyed looks/they cut like hooks / And silence like a sto-oh-oh-one / We live here / Together, dear / Why am I so alo-oh-oh-one?”). Hall’s songs about moribund relationships are always probing and unflinching, dressed in deceptively warm arrangements concealing colder innards.

At the time of her two Elektra albums, her first marriage was ending and her relationship with media producer, Leonard Majzlin, with whom she would spend the rest of her life, was beginning. This new relationship provides the album with a most consoling, uplifting conclusion. New love, more auspicious than any previously experienced, is described in “I Never Thought Anything This Good Could Happen to Me”. It is a cautiously yet unequivocally joyful and spirited love song with a style and structure not dissimilar to Carole King’s. The way the album is bookended, first with songs in which the narrator looks back on sexual and romantic awakening (“Carnival Man”, “Sandy”), and then with one in which she, presumably now a little wiser and more battle-scarred, opens herself up once again to love, is a superb touch.

Like most of the songs on Beads and Feathers, “I Never Thought…” tempts you to play it again and again, to postpone the ending and stay in the music. “I had just met Leonard and fallen madly in love. Within the year or so, it generated a number of songs – “If I Be Your Lady”, “Ain’t Love Easy”, “Hard Times Lovin'”, “I Never Thought Anything This Good…”, “My House”, “Thank you, Babe”, and a few others. I probably could have done an album of songs and just called it Leonard! We married in 1978 and the next week I went into rehearsal for The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. We’ve been married 40 years.”

Beads and Feathers is an immaculately sequenced album; in between the two highs provided by the opening and closing tracks, Hall travels through a lifetime of ups and downs. “Nana”, with its lonely, waltzing piano figure, suggests discarded music boxes, rocking chairs and Edwardian pocket watches. Hall sings of visiting her ailing grandmother. She empathises with her elderly relation’s predicament and asks, “Nana, Nana, are your shoulders getting cold / And were you scared of growing old?”, but deftly avoids any cheapening schmaltz and sentimentality. “The images are vivid because they are real,” says Hall. “My Nana (as they say in Texas) ‘took to her bed.’ People always ask, ‘which came first: the lyric or the melody?’ and in this instance it was the rhythm – the rocking motion of the singer sitting in the rocking chair. The arrangement was worked out in the studio by all the musicians and the guitar solo by Wayne Perkins was sheer inspiration plus a little weed.”

It’s impossible to write about Beads and Feathers without mentioning the penultimate song, “Charlie’s Waiting for the Snow”, one of the rare instances of Hall being recorded alone at the piano. It’s an ominous track that creates and inhabits its own universe. Hall elaborates: “The song was based on the science fiction short story and subsequent novel Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes. In the book, Charlie is a 32-year-old developmentally disabled man who has the opportunity to undergo a surgical procedure that will dramatically increase his mental capabilities. This procedure had already been performed on a laboratory mouse, Algernon, with remarkable results. The story is told by a series of progress reports written by Charlie, the first human test subject for the surgery, and it touches upon many different ethical and moral themes such as the treatment of the mentally disabled.”

“The story has been the basis for television films, a stage play, a musical and in 1968, Cliff Robertson won an Oscar for his portrayal of Charly in the title role. In ’67, I was friends with William Goldman who was hired to do the screenplay of Charly. I think I wrote the song, hoping to have it considered for the movie, but Bill was dropped from the project and another writer, Sterling Silliphant, replaced him. Eventually I just put it on the album. Perhaps part of the receptivity of the song at the time may stem from the fact that in the ’70s, “snow” became one of the many street names for cocaine, which was fast becoming the high roller’s choice of covert social drug. But it’s not what I had in mind when I wrote the lyric.”

Beads and Feathers quickly joined If I Be Your Lady in the cut-outs, despite a rave long-form review in Rolling Stone. Before long, both albums were removed from catalog. “I have no idea why albums take off or don’t,” says Hall, who was briefly disappointed but soon occupying herself with other assignments. “Elektra pushed Carly way more and it became apparent that unless I was willing to completely go on the road, do lots of gigs and promotion, those albums would not lift off. Fortunately, Barbara Cooke beautifully recorded “Ain’t Love Easy”, and it was also used on a Partridge Family episode successfully. I understand it will be used in a new Norman Lear television series. In 1986, I wrote the Off-Broadway musical To Whom It May Concern – it’s a funny and poignant piece that takes place in the minds of a number of churchgoers as they attend an Episcopal service – and I was able to place a number of the songs from the albums in that work. It’s available for production through Samuel French, Inc. I’d love for it to be done in the UK.”

Hall’s time with Elektra came to an end with a non-album single, “The Wah Wah Song”, in 1973. “The Wah Wah Song” (no lyric, just a wacky, catchy arrangement of a melody I wrote) was recorded as a single by Arif Mardin, the preeminent record producer of Atlantic Records at the time. He started out as Neshui Ertegun’s assistant, brother to Ahmet Ertegun another Turkish-American mega-hit record producer. He recorded it because Jac Holzman, President of Elektra Records, thought it might have a shot as a fluke novelty single. It went nowhere and the single was abandoned. The song got its name from the wah-wah pedal — a type of electric guitar effects pedal that altered the tone and frequencies of the guitar signal to create a sound that mimicked the human voice saying wah-wah. Five years later, I reworked the melody and wrote a specific lyric for it; it became “The Aggie Song”, the show-stopping dance number in the score for Whorehouse.“

The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas was Hall’s blockbuster. It spent almost five years on Broadway, spawning at least five concurrent touring productions and winning two Tonys and three Drama Desk awards. It opened on the West End in London at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1981 and became a motion picture starring Dolly Parton and Burt Reynolds in 1982. It is frequently revived to this day. For Hall, moving from the singer/songwriter realm to the theater one was no struggle because the latter was what constituted all her grounding.

“I’m not so sure there was any transition. I wrote a few other musicals, some of which were workshopped, others produced. Unlike other composer/lyricists in the theater, though, I’ve also taken on the challenge of writing music and lyrics outside the constrictions and demands of a book musical – freestanding songs, if you will. Projects such as Free to Be… You and Me or songs for Big Bird or Kermit the Frog, for example, or songs for people singing in cabaret or recording, such as Margaret Whiting, Julie Wilson, David Campbell, Jane Monheit, Amanda McBroom, Chita Rivera. So, I’ve been able to work both in and out of the theater world. But also, part of the success in theater is due to giving back, in the form of other participation. So, I’m a Lifetime Member of the Dramatists Guild Council, I’m a Tony voter and I’ve helped produce educational videos for the Dramatists Guild Foundation”.

Hall’s subsequent achievements include the sequel, The Best Little Whorehouse Goes Public, and an array of additional musical productions, including Paper Moon, Are We There Yet?, and My Name Is Alice. She undertook a series of award-winning cabaret performances of her own work, The Songs Of Carol Hall and, in 2008, a various-artists compilation, Hallways: The Songs Of Carol Hall, came out on the LML Music label, and included Hall’s performance of “My Circle Of Friends”, a song that wouldn’t have been out of place on either of her Elektra albums. The Elektra albums have yet to be significantly revived. Reissues were said to be in the works some years ago but in the end only If I Be Your Lady was released (with no press or fanfare) to streaming and download platforms. A genuine reappraisal is overdue.

* * *

Carol Hall died on October 11, 2018, at home, surrounded by her family. She is survived by husband, Leonard Majzlin, two children, Susanah Blinkoff (screenwriter, songwriter, actor) and Daniel Blinkoff (actor), both based in Los Angeles, and a grandson, Wally Corngold. The author would like to thank Leonard Majzlin for his kind help in facilitating this interview with Carol Hall.