“Whoever said the sky was the limit, wasn’t living where I was living”

— TheMIND, “Mercury Rising”

At the end of his star-making verse on “Ultralight Beam”, Chance the Rapper makes a grand declaration, “You cannot mess with the light. Look at lil’ Chano from 79th.” On first listen, this is an announcement of his newfound stature as a superstar, and especially with his debut on the Saturday Night Live stage, it was easy to believe Chance’s light would shine brightly and be “seen”, if you will, both far and wide. But this final couplet can also be read as a plea. “Look“, he says. “Look“. He’s asking the listener to be active. To really understand who Chance the Rapper is, we need to go back to where he came from. He knows what we will find there if we really take a look.

Art is often an expression of personal experience, as well as a means in the search for a greater awareness beyond one’s own reality. Hip-hop is in the midst of a highly reflective, conscious, and political period that has seen artists injecting profoundly essential perspectives on matters such as race, sexuality, and non-normative individuality into our larger cultural spectrum. Through sound, these storytellers are displaying the realities of their own lives, and in turn, they’re proclaiming vital truths for those often without a voice of their own. The artists who trailblaze and transcend are the ones who provide an essential sense of humanity to the people and places they know firsthand; communities often laden beneath stereotypical narratives they neither own nor believe in. They’re asserting to be heard on their own terms.

The South Side of Chicago is like this; it’s a place some may feel they know without every stepping foot inside the city limits. But what if a place was able to speak for itself and tell its own truth? In 2016, Chance the Rapper became something of an ambassador for Chicago and its communities. By offering an honest and heartfelt take on his surroundings, by remaining independent of major labels, and by injecting a profound sense of hope, positivity, and pride in his hometown, he has provided an opportunity for Chicago to shape its own cultural destiny. Through his music and activism, Chance has managed to bestow the brightest of colors upon a city that is too often depicted in only black-and-white.

Chance the Rapper was everywhere in 2016, appearing at major festivals, on late night television, on Saturday Night Live (twice), and even at the White House tree lighting ceremony. Within that same time frame, however, his hometown of Chicago experienced one of its most tragically violent years in recent memory, routinely making national news. This contrast speaks volumes. Take, for example, the date 11 August 2016. On this day, Chance the Rapper graced the “New Pioneers” issue of Billboard Magazine, starred in an advertisement for Nike in which he premiered a new song “We the People”, and was featured on President Obama’s official Summer Playlist. It also marked three months since the release of his third mixtape Coloring Book, which made history as the first album to chart on the Billboard 200 solely on streams. On that very same day, The Chicago Tribune reported that nearly 100 people had been shot in Chicago in the prior week. Two days before had been the deadliest day of gun violence in 13 years, with nine people murdered over a 24-hour span. One of the victims was ten-year-old Tavon Tanner, who was shot in the back as he played with his twin sister on their front porch.

How can a city simultaneously swallow so many lives while also catapulting a single young soul to uncharted new heights? Sadly, that’s always been the tale of Chicago: a city with two extremely disparate and segregated realities. This is a city with a rich immigrant community, yet the minority populations here each have their own history of blatant and routine racism and violence directed toward their communities, their people. The disconnect between the largely white neighborhoods to the North and the predominantly black neighborhoods on the South and West sides, however, most plainly lays bare the foundations of institutuional racism in Chicago.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

Chancellor Bennett was born on Chicago’s South Side in a predominantly African American community called West Chatham, about ten miles south of downtown. Chatham has one of the highest rates of violent crime in the city and growing up in that environment, Chance was exposed to visceral traumas that threatened to consume him whole. After witnessing the murder of his close friend and fellow MC Rodney Kyles, Jr., at the age of 18, music became the conceivable golden ticket out of the cyclical destructiveness that surrounded him. We know this from the first song Chance ever publicly released, “14,400 Minutes” off the mixtape #10Day, “I was standing right there / an inch away from Heaven, a million songs from right there.”

From #10Day to Coloring Book, Chance has remained unapologetically transparent about his life, his home, and most importantly and uniquely within hip-hop, his feelings, particularly in regards to violence. As an essential art form, rap music has a history of incorporating and repurposing the realities of gang and police violence to connect, to educate, to heal, and in some cases, to display power. In regards to Chicago, the South Side has been a focal point of violent lyrics, most recently with the rise of Drill, a style of hip-hop routinely denounced for its sensationalistic influence on children and teenagers, as well as its motivation to capitalize on society’s voyeuristic interest in violence. Chance the Rapper, however, has taken a conscious approach in his perspectives on violence, a style similar to that of Common, Talib Kweli, Mos Def and Nas. His music has an almost childlike innocence and optimism, yet it’s mature in its thoughtfulness and accountability. His compassionate viewpoint is on full display throughout his work, and particularly in the song “Paranoid” (Acid Rap, 2013):

I heard everybody’s dying in the summer,

So pray to God for a little more Spring.

I know you scared

You should ask us if we scared too.

If you was there

Then we’d just knew you cared too.

These are not prideful boasts, scare tactics for power and popularity, or shock value for the sake of entertainment. These words convey vulnerability. It’s one thing for an artist to take a stand against violence, which Chance has made a key platform within his influence, but it’s another thing altogether for someone to expose such a profound and universal fear of its grip on one’s friends, family, and hometown. Many have deliberated hip-hop’s uniquely intrinsic relationship to violence as both a product of and reaction to the fundamental role violence has played in the black American experience. Through this lens, Chance’s music can be understood as both a tool for personal self-expression and as a conduit for a larger-scale dialog and understanding. While an artist’s relationship to their audience can often be similar to that of a therapist and patient, Chance has never asked his fans to pay to hear his feelings.

From day one, Chance has held strong in his resolve to give his music away for free, as both a nod to mixtape culture and in maintaining his artistic control and accessible relationship with his fans. While he was not the pioneer of free music by any means, Chance the Rapper’s success has helped turn this once-revolutionary idea into a serious consideration for artists and industry heavyweights alike. For example, with the album Surf, the band The Social Experiment’s debut on which Chance was heavily featured, he convinced Apple to release it on the iTunes Store for free. It was the first and only time the tech giant had done so with a full-length album, and as a result, Surf was downloaded 618,000 times in its first week, with over ten million individual track downloads.

It’s also likely not a coincidence that shortly after the release of Coloring Book, the Grammy’s overturned a previously unyielding guideline that prohibited albums not sold through traditional retail methods to be considered for awards. Simply put, the world wasn’t ready for a trajectory like Chance’s until very recently, which is one of the reasons why he’s one of the most now icons we have. In an industry of artists and corporations chasing taillights, the masses have found something incredibly admirable, thought-provoking, and hopeful about Chance; he’s the outsider leading the pack to something new and brighter. In some ways, Chance the Rapper has become more of a symbol than the 23-year-old he really is, and this is largely due to what is arguably his most unique asset within the music industry landscape: his resolute stance and ability to remain independent of major labels.

The Outsider on the Inside

As an independent musician, Chance has no contractual obligations to a record label or publishing company, which gives him complete ownership over his intellectual property and his brand. These are fairly new concepts within mainstream music, and while it’s an inherently risky strategy to work outside of the system, independence has played an enormous role in his success and in his ability to tell Chicago’s story his own way. His independence has allowed him to speak on the ugliness and beauty of his home without the constraints of censorship or political ties. It has allowed him to tap into the city’s historic and grassroots music infrastructure without needing to relocate to “where the industry is” on the coasts. It has allowed him to experiment, to be constantly interactive with his followers in new and exciting ways, and to release all of his music for free. It has allowed him to appear inherently authentic and truthful, while his industry peers give up control of their music to faceless institutions for profit. It has allowed him to stay in the city he loves — a city where “every father, mayor, and rapper jump ship” — and to embark on a mission to make the South Side better for his daughter than it was for him as a child. Chance is a symbol for Chicago; a “blueprint to a real man”, as he calls it. By remaining independent, he has made something of and for himself against all odds, and in turn, has become an inspiration for others to do the same.

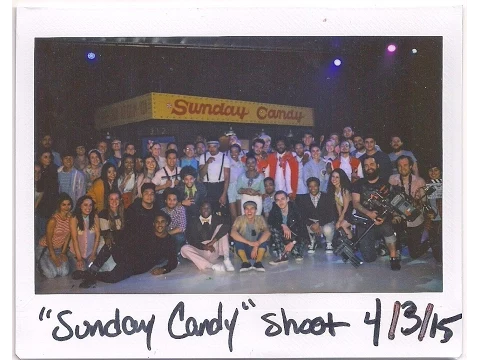

In September 2016, Chicago Magazine compiled a list of young Chicagoans who are bringing positive change to Chicago through the arts, and all of them are in some way connected to Chance. Jamila Woods, who sang the chorus on the Surf hit “Sunday Candy”, released her critically-adored album Heavn as a celebration of “Black Girl Magic”. The Social Experiment, led by Nico Segal (aka Donnie Trumpet), acted as Chance’s backup band during his Muhammad Ali tribute at the ESPYs. Austin Vesley, a rising filmmaker on Hollywood’s radar, shot the intricate one-take “Sunday Candy” video, and just wrapped his feature film debut Slice staring Chance as a werewolf framed for a killing spree (the film has been picked up by A24 for distribution, and is due out this fall).

There are many other notable Chicago artisans who share Chance’s orbit, such as Vic Mensa, who made headlines for his protest anthem “16 Shots” for Laquan McDonald, Noname, who was rightly featured on nearly every “Artists You Need to Know” list of 2016, the relentless visionary poet/activist Malcolm London, and the trailblazing visual artist and storyteller Hebru Brantley. With the assistance and guidance of cultural organizations fostering this scene, including Young Chicago Authors, the Logan Center for Arts, and YOUmedia at the Harold Washington Library, every one of these artists have made their Chicago upbringings a staple in their work and social messaging, and have combatted negativity with remarkable talent and collaborative spirit. People are beginning to take a much-needed second look at Chicago, and it’s in large part because of these “New Bohemians”, as Chicago Magazine labeled them, and the stories they are telling.

There’s hope to be found in the youth of this city. Through politics, social movements, and the arts, the next generation often carries the burden of belief that they will be the ones to really change things. As Sam Cooke once prophesized, “A change is gonna come”, but even he would admit that despite the most progressive and energizing of forces, the critical foundational changes needed in Chicago will likely take years, even decades, to flourish. No one expects a song to repair the division and brokenness this city has experienced, nor for it to fully convert the perceptions of the larger public. However, the renaissance brewing in the South Side arts and activism scene is causing a fascinating and vitally potent shift in the way Chicago is viewed from both the outside-in and the inside-out. For those on the ground here in Chicago, we can feel the movement happening, and it’s being assisted and soundtracked by a vibrant, young, communal, and artistic proclamation of faith, redemption, and hope. For the South Side, this embrace of light is nothing short of radical.

Coloring Book, to steal from Chicago’s own Kanye West, is a pure “Ultralight Beam”. It’s so unrelentingly positive and overflowing with joy that it feels both revelatory and somewhat out-of-time with the grimness of today. It’s a portrait of a man who has risen above negativity in all its forms, stood tall against convention, brought beauty out of ugliness, and most inspiringly, reaches back to help others climb to their own heights. Outside of music, Chance has dedicated his time, talents, money, and influence toward making a real difference for those in Chicago who need it most. Chance has continued to host open mic events for high school students seeking an audience and an opportunity to perfect their skills. He has personally chaperoned groups of young children to several Chicago institutions that are often out-of-reach for residents of the South Side. And to combat Chicago’s brutal winters, he established the Warmest Winter program, which provides homeless men and women with jobs manufacturing self-heating coats and sleeping bags for fellow homeless people in the city.

Most recently, Chance led a march of thousands of impassioned young voters through the barricaded streets of Chicago to the West Washington early voting site the night before the US Presidential election. These acts of community, consciousness, and advocacy are both rejuvenating and hugely shareable, and make for highly productive strides in realigning the national perspective of Chicago as a city of resilience, hopefulness, and unity.

In the summer of 2016 Chance put the South Side on the world’ stage as he hosted the Magnificent Coloring Day Festival at US Cellular Field. Featuring Alicia Keys, John Legend, Skrillex, Lil’ Wayne, and others, it was the first concert held in the stadium in over ten years, and it blew away the previously held attendance record for the venue with roughly 50,000 in attendance. By hosting the fest at “the Cell”, rather than downtown or on the north side, the statement was clear: this was a day specifically designed to celebrate the spirit of Chance’s home, and to show the true beauty and artistry the South Side and its people have to offer. Fans flew from around the world to witness Chance’s bold homecoming and were treated to a truly joyful embrace of music, culture, and rousing love. Kanye even showed up for a surprise set, proclaiming enormous pride in the major accomplishment Chance had put together, the likes of which he himself had never managed. If Kanye’s appearance proved anything, it was that while he will likely be remembered as Chicago’s most influential musical son, a torch has been passed to the next generation of artistic and social genius. Seeing Chance’s arm slung over his idol’s shoulder as they walked backstage, it was apparent that Chance’s own fame and accomplishments will one day open the gates for the next generation of young and passionate visionaries. The South Side kids growing up inspired by Chance the Rapper will have the opportunity to further his message, and to continue to paint a three-dimensional picture of their city as a place of family, art, hope, revolution, imagination, humanity, and possibility. In time, this will surely be understood as his greatest gift to the place he calls home.

It’s now Chicago’s turn to take the opportunity Chance has provided and run with it. The city has taken strides in acknowledging his accomplishments, such as naming him “Outstanding Youth of the Year” and “Chicagoan of the Year”, and has begun collaborating with his team on art and community projects. There are even murals of Chance painted near his childhood home on 79th and Evans as part of Chicago artist Chris Devin’s “Positive Imagining Campaign”. However, it’s unknown if a larger scale political movement will result from Chance’s efforts, or what the widespread cognitive shift that he’s continuing to inspire will lead to. But regardless of what the city does next, Chance has humanized Chicago and the people it has forgotten, and in doing so, has created fundamental change. Whether it’s wearing a White Sox cap in his national TV debut, or proclaiming “City so damn great I feel like Alexand” in his hit “Angels”, his message serves as a constant and prideful reminder of where he’s from and what we can all aspire to be.

Chicago has always been a deeply and painfully segregated city, and particularly on the South Side, it can often feel like its own world; one that most people will only be exposed to through images on a screen or through the words in a song. There is enormous power in being the gatekeeper of a larger public opinion, and through his stance on violence, his leading example of independence, and by remaining true to his roots, Chance the Rapper is inspiring a divergent South Side movement to show not only what Chicago is and was, but what it can be.

The cover of #10Day, Chance’s first mixtape, sees him as a kid. He’s looking up at the sky, his mouth agape with awe and wonder at the hugeness of the world beyond him. You can almost hear him asking “What’s out there for me?” On Coloring Book, Chance the Rapper looks down, grinning as if to say to his younger self, “You’ll see soon enough.”