Keiler Roberts lives in a deadpan universe ruled by a bipolar God. Her graphic memoir, Chlorine Gardens, is a fractured chronicle of self-deprecatingly hilarious yet harrowingly moving vignettes from the edge of her private yet oh-so-familiar abyss. Really, she has it pretty good: a comfortable life in a suburban home filled with loving family members and ample art supplies. Also, her grandfather just died and she’s been diagnosed with MS. But rather than best-of-times worst-of-times rants, Roberts’ humor is perpetually even-keel—a line as endearingly flat as the never-quite-smiling, never-quite-frowning mouths she draws on her and family’s faces.

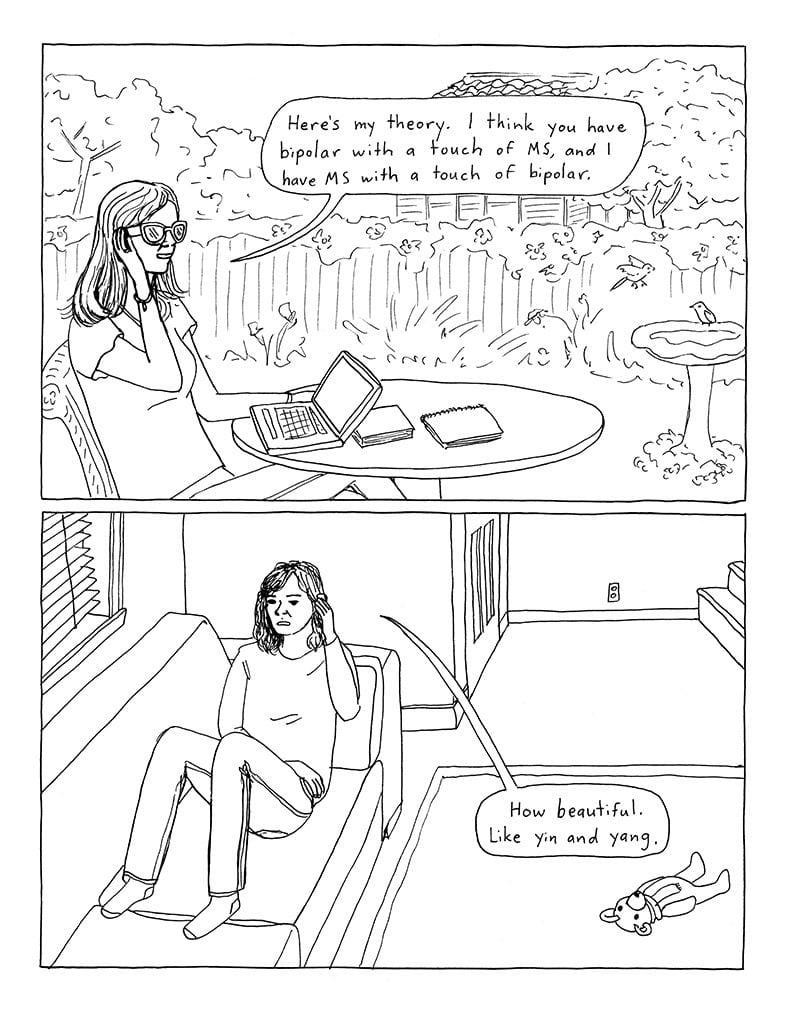

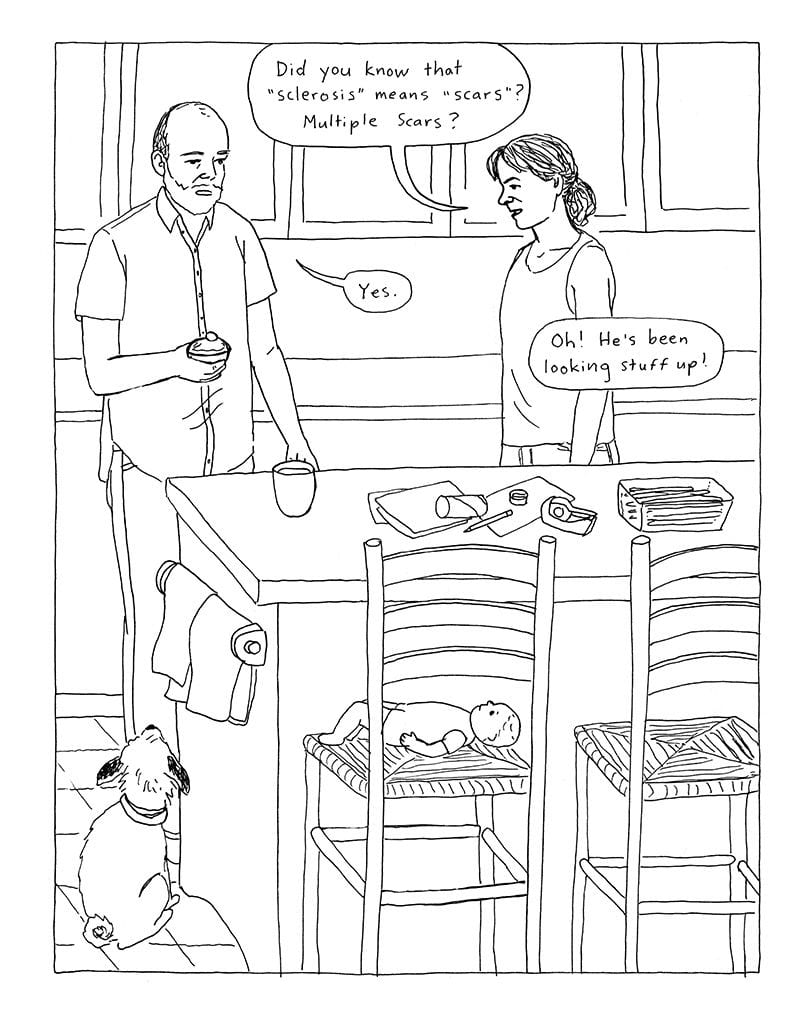

Given her anti-sentimental tone, Roberts’ drawing style is appropriately sparse: thin, black contour lines give her world realistic proportions, but without crosshatched shadows and depth. All shapes are empty shapes. The universe is not only colorless, it rejects gradations too. But her simplified renderings are not cartoonishly exaggerated, either. Though any photographic source material feels distantly filtered, its underlying realistic integrity remains. This is our world—just less so.

Roberts matches the visual flatness of her panel content with similarly flat layouts of mostly 3×2 and 2×2 grids, punctuated by occasional full-page images. Each panel is framed by the same thin black lines that shape the images, gently challenging the conventional illusion that the white of the page background visible in the gutters is any different from the white of the story-world spaces inside the frames. In both cases, there just isn’t a lot holding everything together.

And yet her world, her family, Roberts herself—they do hold together, in part from the warmly ironic wit she threads through each scene. As a parent who kept a journal of the most endearing and inappropriate things my children said growing up, I know the pitfalls Roberts avoids as she chronicles her home life with an early school-aged daughter. In other hands, the six-year-old Xia—even as she’s echoing her mother’s “shit” and “goddamned” expletives—would be too cute, just a variation of parental bragging.

Instead, moments with Xia, like Roberts’ self-portrayal generally, is grounded by the graphic memoir’s overarching tone of struggle. Yes, life may be pretty goddamned good—but what’s that have to do with being happy? The memoir opens with Roberts telling Xia her birth story, yet by the end of the sequence she’s clearly stating things not meant for her daughter’s ears. “I think,” Roberts’ drawn self later tells her viewers, “I started making comics so I could stop fearing the loss of my irreplaceable things.”

“Things” are central. Roberts lists some of her favorites and least favorites—including Coltrane’s jazz cover of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “My Favorite Things”. Her favorite glass appears in a wallpaper pattern beside a vodka bottle on the inside of the cover. It appears again on the inside of the back cover, except beside a carton of milk. Somewhere between, she mentions that she’s stopped drinking and that “I never use my favorite glass anymore because I’m afraid I’ll break it.”

She later lists first symptoms of MS, jokingly calling each her favorite thing too. “Nothing,” she explains, “exists without meaning and sentimental value,” and so “every object blooms with associated memories and feelings.” As though to prove it, she ends the memoir with her mother lamenting that she has only “four of those wonderful frozen cheeseburgers from Costco left. They stopped carrying them.” The comment would seem aggressively mundane, and though Roberts’ character responds with only a simple “I’m sorry,” ten pages earlier she drew her dying father eating one of those cheeseburgers, calling it the moment she felt the loss of him.

Much of Roberts’ skill is in her understated use of the comics form—which is based on gaps and absences and so kinds of loss too. Roberts often leaves out key, dramatic moments. One panel caption explains that her beloved dog “bit some people”, and in the next she’s driving him “to the vet to put him to sleep”. She avoids not only the biting incident but the immediate drama of its aftermath when the victim presumably contacted authorities who agreed that the dog had to be put down. Instead, Roberts draws her “perfect” pet in the front seat, under the caption: “He sat up calmly.” In the next panel, she’s alone in an examination room, with her hand on the blanket-covered dog. The panel reads: “Scott was in New York.” The understated fact echoes with a blur of emotion—all unverifiable by her expressionless face.

That kind of image and word juxtaposition is another of Roberts’ comics skills, the way she plays the two modes against each other for subtle contradictions. When she states that “Scott sometimes watches football,” she draws her husband swinging their daughter around the living room as they shout “Touchdown!”—it’s unclear whether the TV is even on. When she’s explaining the nostalgia-like loss she feels in all objects, “It’s a wanting that can’t be satisfied,” she draws an angled eBay image of a “Barbie mixed lot from the 80’s” on the phone held in her hand. The mundaneness undercuts the spiritual depth of her words, as though her internal artist is gently mocking her internal writer.

The effects are subtle, but subtle is as good as it gets in Roberts’ universe. She posits a bipolar God to explain how “inconsistently great and terrible his creations are”, and then counters that volatility with her own deadpan consistency—though with just enough hint of a Mona Lisa smile to betray the love and joy found just beneath the starkly drawn surface of all things.