Bassist Christian McBride has been state of the art on his instrument from a young age, a player with the tone, time, and technique to play with anyone in music regardless of genre or circumstance. His roster of record dates and star turns spans Sonny Rollins to Renee Fleming, Pat Metheny to Queen Latifah, Paul McCartney to McCoy Tyner. As a leader he fronts a big band, a strong mainstream quintet, a trio, you name it.

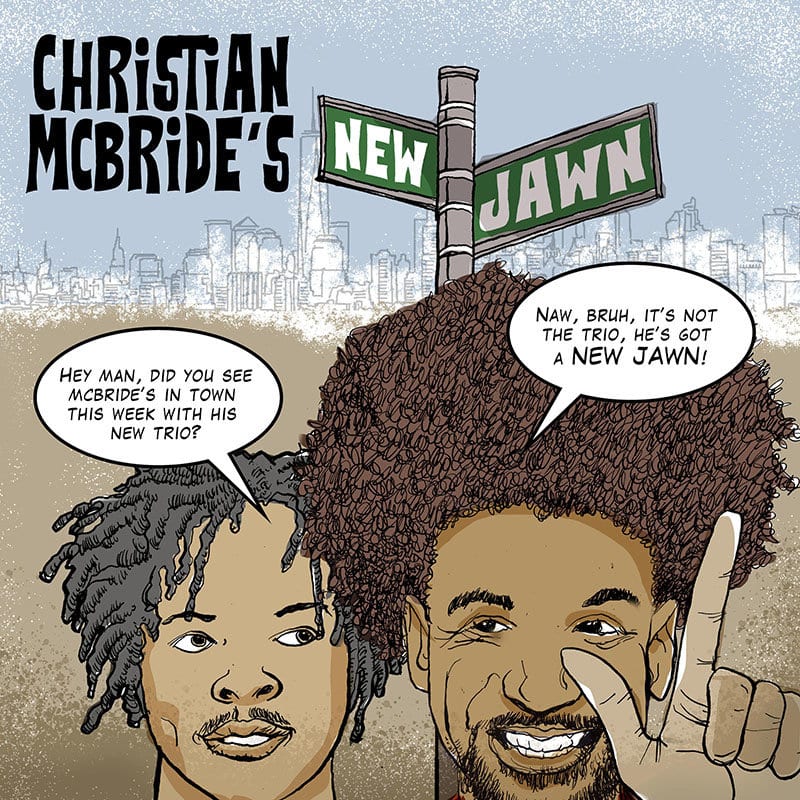

His latest, Christian McBride’s New Jawn, however, feels as fresh as anything he has ever done. While McBride is, himself, old reliable— a huge sound, incredible swing feeling, barreling energy—this band and its musical approach have more edge and daring than the usual McBride project. The date, recorded last year in St. Louis, features a piano-less quartet with Josh Evans (trumpet) and Marcus Strickland (tenor sax and bass clarinet) on the front line and drummer Nasheet Waits in the rhythm section with the leader. The compositions from all four members of the “New Jawn” with Wayne Shorter’s “Sightseeing” (written for Weather Report). If McBride’s profile as an artist has been almost aggressively mainstream and accessible, his New Jawn seems like an act of letting go and taking more chances. It is a cool breeze of daring that still hits a sweet spot of swing and soulfulness.

McBride’s two originals are very different but both as engaging as any mainstream jazz. “Walkin’ Funny” features a soul-drenched, blues melody, but it is seated over time feeling that is simultaneously swinging and strange. As the title suggests, the bass line “walks” in that classic “four on the floor” jazz style, but then… it doesn’t. The time signature shifts, speeding up then slowing down, all within just a handful of bars that create the tune’s structure. It is so ingeniously constructed, however, that it sounds entirely natural and swinging despite how hard it is to tap your toe to it. The players don’t take traditional jazz “solos” on the form, but they collectively let loose over a chorus or two, themselves speeding up and dragging out the writing, trading squiggles and squawks, and bits of expressive atonality—all while Waits plays around the time like a happy toddler. It is less than three minutes long—the length of a pop song—but it lets you know that all of this album is going to stretch out your ears.

McBride’s “John Day” is a mournful, minor tune in 6/8 time and blends trumpet and bass clarinet to moving effect. The Waits/McBride rhythm team is ideal, with the drums rolling and tumbling like the surface of the ocean as the bass keeps everything grounded. Evans’ solo is tart and blue, staying mostly in his middle range, a conversation with Waits’ accents and provocations. The bass clarinet continues the dialogue, but it is McBride’s solo that highlights the track, using double time and wonderful melodic invention to steal the show.

Evans is the least-known member of the band, but his impressive list of sideman appearances and his two compositions here attest to his talent. “Pier One Import” is a crackling theme that will put jazz fans in the mind of Freddie Hubbard. It begins with a sharp, brassy fanfare that harmonizes trumpet and tenor sax in a pungent way, but then the tune simmers into a more subdued written theme that sets up solos on a modified Latin groove. Here as throughout New Jawn, there seems to be nothing missing despite the absence of a piano or guitar—the writing and playing are so full that all the harmonic information is felt through the four voices. Evans’ “Ballad of Ernie Washington” is a lovely melody for trumpet alone, adding tenor for just some counterpoint, briefly. McBride covers the accompaniment without needing piano here as well, and the horn solos are arguably two highlights of the date: lyrical and captivating, wasting no notes.

Strickland seems to be on everyone’s session these days, and his two original tunes remind you that e loves that old Blue Note sound just as much as he is in touch with newer music. “Seek the Source” is a contemplative blues set over a throbbing groove. McBride plays a syncopated pedal point note that holds steady for two bars at a time before shifting through the blues pattern. “The Middle Man” is a pulsing swinger that contains thrilling stops and half-time slowdowns. Strickland takes the lead solo, fluent and rich in ideas, evoking the legacy of Joe Henderson as he avoids the usual patterns saxophonists sometimes lean on.

The most daring writing comes from Waits on this date. “Ke-Kelli Sketch” begins with a duet for McBride’s growling bowed bass and Waits’ kit—a sort of free prelude. The tune then shifts into a fast walk on eighth notes that don’t break up into standard bar lines. The horns have only a sketch of a melody, harmonizing in descending patterns as the swing breaks up momentarily before starting up again. The mood is one of mystery, as Evans solos gesturally, finally breaking into a declarative blues statement that seems to be unlocking doors toward a destination that becomes more urgent as Waits’ drumming develops more clarity and power. Strickland’s solo is met by yet another rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment—a swaggering 4/4 feeling that has a bit of Motown in it. This vibe dissolves back into freedom, with McBride picking up his bow again and the prelude becoming coda. Hearing this kind of “out” playing on a Christian McBride album? Yes, please.

Waits’ “Kush” has appeared on other recordings, a modern ballad that seems like it has been around for decades, steeped in the kind of Ellingtonian melancholy that teases you with pleasure even as it seems to come out of sorrow. Strickland and Evans sound like old hands here, not only turning in lovely improvisations but blending their tones with sensitivity.

The arco bass solo from the leader, undergirded by an elegant bass clarinet line, will put you in the mind of McBride’s classical training at Julliard, not to mention his penchant for always sounding like a voice, a man who is speaking from the heart. What New Jawn does so well is remind us that Christian McBride’s sincerity and soulfulness can come in some new flavors. The truth is, the musicians on this date do not seem subordinate to a McBride aesthetic but are clearly engaging a master as equals. And that suits McBride just fine. In fact, New Jawn proves that it brings out the best in him.