After centuries of near-silence or of being silenced, humorists have emerged in recent decades as the premier public antagonists of religion. Yet, despite the commonality of satire leveled at religion today, most have restricted their jibes to institutions of faith rather than faith itself.

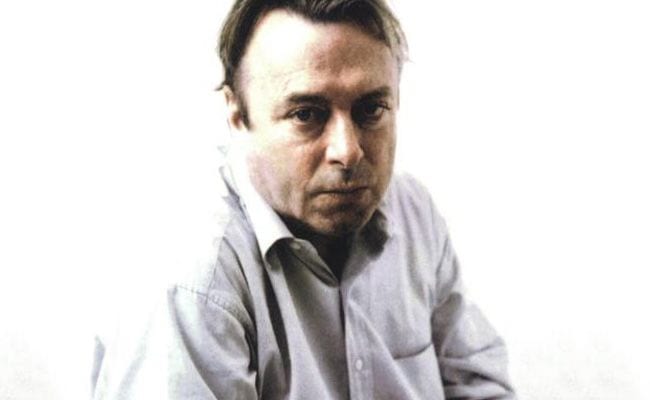

Journalist and public intellectual Christopher Hitchens, ever the contrarian, has no such parameters around his cutting wit. Declaring religion “totalitarian” in essence and god a “celestial dictator”, Hitchens rages not only against organizations, leaders, and practitioners, but against the act of faith itself. As such, this Anglo-American provocateur is not content with being tagged an “atheist”, for that term allows for those who might wish there were, or that they could believe in, a god. Instead, he prefers the label “antitheist”, reflecting his combative stance, one that proposes that “religion poisons everything” (God Is Not Great. New York: Twelve, 2007. p.15).

In the early ’00s, Hitchens emerged as one of the more vocal advocates of what has sometimes been called “new atheism”. Alongside scholar-intellectuals Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, and Sam Harris, Hitchens was hailed—or nailed—as one of the “four horsemen” of this emerging public movement. All were on the advisory board of the Secular Coalition for America, an organization advocating for reason and science in public policy, prioritizing secularism as the only way to guarantee representative freedom for all. However, while his fellow horsemen drew from their science backgrounds, articulating in often dry, academic language, Hitchens played by his wits, speaking from experiences and viewpoints acquired as a life-long student of world affairs.

Less a comedian than a wit, Hitchens developed his distinctive argumentative style while studying politics, philosophy, and economics at Oxford University during the ’60s. There, he learned how verbal barbs and linguistic dexterity can be potent weapons of rhetoric in intellectual combat. Anyone who has witnessed the banter of “Question Time” in the British Houses of Parliament will know of what I speak. Such methods are deeply embedded in British humor, particularly in its literature and public speaking. Noting how Hitchens embodies the persona of the quintessential Oxford wit, Lynn Barber once described him as “a parody of an English gentleman”. Like Oscar Wilde, Evelyn Waugh, and P.G. Wodehouse—all beloved by Hitchens—such (faux) upper-class aesthetes, argues Barber, often “care more about writing than they do their subject” (“Look who’s talking“, The Guardian, 13 April 2002). Such a backhanded complement speaks to the self-conscious persiflage of Hitchens’ roaming ruminations on the myriad dangers and damage religion has begot.

If Hitchens learned the art of wit from literary forerunners like Wilde, Waugh, and Wodehouse—as well as Georges Elliot and Orwell—certain contemporary comrades also encouraged the cutting edge he would acquire in his rhetoric. Salmon Rushdie, Martin Amis, Ian McEwan, Julian Barnes, Susan Sontag, and Clive James are all renowned for their own often savage literary wit; they were also all close friends of the recently deceased Hitchens. Like a modern-day Algonquin club, in his memoir, Hitch 22, the journalist recounts the quips and repartee amongst these great writers, each inspiring the others to public provocations and bolder outspokenness. However, as Rushdie, in particular, was to discover, satire and scorn, when directed at religion, do not always elicit (in all) either a belly laugh or even a temperate smile.

The aggressive antitheist point-of-view that came to dominate Hitchens’ writings by the turn of the century was arrived at by personal as well as political circumstances. In 1989, Rushdie published a fictional novel, The Satanic Verses, in which he satirized aspects of Islam and its holy book, the Koran. While well-received by the literary critical community, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini was less enamored of its content, promptly issuing a “fatwa”, a declaration offering financial reward to anyone who assassinated the novelist or any others associated with the publication and distribution of the novel. Although Rushdie managed to avoid such retribution by going into hiding, others in his publishing camp were not so fortunate, three translators suffering murder attempts, one fatally.

These gangster-style hits and threats were accompanied by often violent protests against the novel in cities around the globe, sparking innumerable debates in the media and beyond over the attendant issues of freedom of speech, religious rights, and multiculturalism in the modern world. A culture war that had been smoldering for decades—if not centuries—between western democracies and middle eastern theocracies caught fire on the frontlines of myriad societies. At the forefront of the ensuing analyses was Hitchens, who used his posts at The New Statesman, The Nation, and later, Vanity Fair, to weigh in on the plight of his friend and the surrounding international concerns.

Regarding the incident, Hitchens reflects in his memoir: “I felt at once that here was something that completely committed me” (Hitch 22: A Memoir. New York: Twelve, 2010. p.268). Regarding the literature itself, he assessed the unfolding cultural discord as a clash between humor and religion, saying of Rushdie, “He ignited one of the greatest-ever confrontations between the ironic and the literal mind” (Hitch 22. p.267), and that the religious fundamentalist (or literal minded) always sees the ironic mind as “a source of danger” (God is not Great. p.29).

“State-supported threats of murder accompanied by sordid offers of bounty” was how Hitchens interpreted the fatwa, adding of the saga, “It was… everything I hated versus everything I loved In the hate column: dictatorship, religion, stupidity, demagogy, censorship, bullying and intimidation. In the love column: literature, irony, humor, the individual and the defense of free expression” (Hitch 22. p.268). For him, the whole affair was a microcosm of an ongoing war over civilization itself, one he increasingly saw being played out in terms of the values of the secular versus those of the sacred.

As much as Hitchens was horrified by the fatwa and its advocates, he also reserved scorn for those spokespeople in the West whom he felt were either capitulating under the intimidation or running scared from it. Some of these “traitors” resorted to blaming the victim (Rushdie) and/or excusing the violent perpetrators. Hichens was incredulous that the Archbishop of Canterbury, Vatican representatives, the Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel, and the British Chief Rabbi all blamed the uproar on the “blasphemy” of Rushdie rather than on the terrorism of the “ultrareactionary mobocracy” (Hitch 22. p.270). Freedom of expression, democracy’s most prized value, was at stake for the journalist, and all he saw was a tepid or warped response from weak-kneed western apologists.

If the Rushdie saga brought into focus the nature of the contemporary culture war—as Hitchens perceived it—9/11 confirmed his antitheist stance as well as who and what constituted the enemies of the era. No longer was it possible to simply turn the other cheek in the face of threatening terrorism, felt Hitchens. Moreover, no longer was it possible to excuse or historically rationalize such behavior, as some “multi-culti” scholars continued to do (Hitch 22. p.270). This was war—and its enemy was “fascism with an Islamic face”.

Once a card-carrying Trotskeyite, 9/11 and its left-leaning apologists (“the Chomsky-Finn-Finkelstein quarter”) uprooted Hitchens from his former ideological camp and into one he suddenly found himself sharing with the neoconservatives of the Bush administration (“He Knew He Was Right” by Ian Parker, The New Yorker, 16 October 2002). Later, he admitted that abandoning his “secular faith” in Marxism was “not without pain” (God is not Great. p.151), but that the “a la carte” politics he was left with was by no means “a soft option”, though it was “liberating” (Hitch 22. p.422). As for many on both the left and right, 9/11 shifted ideological concerns away from issues of class and economics and towards politicized faith. “Religion is going to be the big subject until the end of my life. And I want to make an intervention”, vowed Hitchens (“He Knew He Was Right”).

Hitchens’ journey from a Trotskyite that counted Noam Chomsky and Terry Eagleton among his comrades, to a “laissez-faire” figure more comfortable in the company of Paul Wolfowitz and other neocons—whether sparked by 9/11 or by the Rushdie fatwa—was certainly facilitated by the writer’s growing sense that extremist religion has become the enemy of our times. For him, “Islamic fascism” threatens our very civilization, and apologists from the Left, such as Chomsky, are rhetorical enablers of such terrorism (Ashley Lavelle. The Politics of Betrayal: Renegades and Ex-Radicals from Mussolini to Christopher Hitchens. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013. p.57).

This shift from Left to Right amounted to “apostacy” in the eyes of many veterans of Marxism. Eagleton bemoaned the loss of an articulate public intellectual for the Left, while Ashley Lavelle, in her book, The Politics of Betrayal, called him a “renegade” whose “over-cooked prose” is consistently inconsistent (p.150). She finds particular irony in the title of his memoir, “Hitch 22”, which denotes the kind of contradictions and paradoxes that once earned him the moniker “hypocritchens” when the writer was at Oxford (p.221). Lavelle sees more style than substance in his eloquent insult humor, suggesting that his “lashing out… was designed merely to grab headlines and force people to read his work” (p.222). For her, Hitchens is incapable of being an authentic antitheist because that would require authentic commitment—something he has always lacked. Instead, 9/11 gave him, in his words, “exhilaration” and the opportunity to have “fun” again in his writing (p.222). “Hitchens needed a crusade”, she argues, not to fight for, but to write for (p.222).

If Lavelle’s complaints are any indication of the kind of blowback Hitchens has received in recent years, its heat pales when compared to the reactions he has received from the right, particularly the Religious Right. In his book, God and the New Atheism, John F. Haught, Senior Fellow in Science and Religion at the Woodstock Theological Center at Georgetown University, responds to Hitchens and his fellow “horsemen”, Harris and Dawkins, charging them and their “new atheist” books with “flaws”, “fallacies”, and “inconsistencies” (God and the New Atheism: A Critical Response to Dawkins, Harris, and Hitchens. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008. p.xiii). Haught highlights Hitchens’ “venomous sarcasm” (p.29) and “derision” (p.68) aimed “exclusively at the softest points in the wide world of faith” (p.63). William A. Donohue, spokesperson for the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Liberties, goes further, charging the journalist with anti-religious bigotry (“Bill Donohue Must Resign, for the Good of American Catholics” by Alex Wilhelm, Huffington Post, 16 June 2010).

Whatever one’s views of Hitchens’ brand of antitheist rhetoric, one can surely not charge him with intellectual cowardice or with hiding behind his writing. Few public intellectuals graced more stages, nor debated more with his adversaries, than Hitchens did in the final years of his life. This led to some unlikely encounters, such as his nationally televised debate with former Prime Minister, Tony Blair, on the (de)merits of religion. His series of exchanges with Presbyterian preacher, Douglas Wilson, on whether or not Christianity is good for the world, were even edited into a 2009 full-length documentary film entitled Collision.

Despite the scoldings from Ashley Lavelle and her like, Hitchens kept to his antitheist cause, writing and debating in his inimitable style of wit and hyperbole, even as esophageal cancer debilitated his health. On 11 April 2011, a few months before his ultimate demise, Hitch was forced to cancel a scheduled appearance at the American Atheist Convention. In a note of apology he explained why his health would not allow him to attend the gathering; he then wished the group well, signing off, “And don’t keep the faith.” (“Christopher Hitchens defiantly atheist in the face of death“, Christian Today, 27 April 2011).

Were he still alive today, there’s little doubt that his would have been among the less tentative or conciliatory contributions to current debates surrounding the recent Charlie Hebdo tragedy.