The turn of the 21st century found the world obsessed with time. When people weren’t musing over the end of days as the ’90s ran out, they worried that their computers might forget what year it was on New Year’s Day 2000. The fear of sequencing errors caused by programmers’ memory-saving practice of abbreviating years by their final two digits led companies and governments all over the globe to reformat dates to avoid system failures. The near hysteria that ensued made the “Y2K bug” convenient cultural shorthand for all the anxiety surrounding the arrival of the new millennium.

A number of films recorded these preoccupations with time, memory, and an uncertain future. Run, Lola, Run (Lola Rennt) (1998) offers three alternative narratives that resolve the initial plot conflict; Go (1999) tells the same story from the perspectives of three characters, one after the other; Timecode (2000) presents four facets of its plot simultaneously, by means of a screen divided into four frames; and Memento (2000)—just released in a tenth-anniversary Blu-ray edition—unfolds in sequences placed in reverse chronological order.

Beyond its novel narrative structure, Memento contributed to millennial fear a human version of the Y2K bug: Leonard, whose head trauma has rendered him unable to make new memories. This affliction enjoyed a mini-epidemic in the years preceding and following 2000. Winter Sleepers (Winterschläfer) (1997)—like Run, Lola Run directed by Tom Tykwer—also has a character plagued by short-term memory damage, who like Leonard takes photos to help him remember. Hollywood eventually played the figure for laughs, with the forgetful Dory in Finding Nemo (2003) and the lovable, but memory-impaired Lucy from 50 First Dates (2004).

After 9/11, the plight of Memento‘s hero gained resonance as studio executives began to consider how to represent the tragedy on film. Following the appearance of David Grann’s New York Times Magazine profile of firefighter Kevin Shea (“Which Way Did He Run?”)—who can’t remember what happened to him at Ground Zero on the day of the attacks—the young man’s story gained traction in Hollywood as the 9/11 version of Memento.

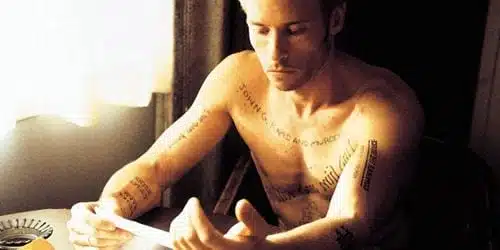

Like a true believer convinced the world is always about to end, Leonard (Guy Pearce), injured in the assault that killed his wife, lives only to find the assailant and exact revenge. Unable to transfer new experiences from short-term to long-term memory, Leonard compensates by tattooing “facts” about the case on various parts of his body, and taking Polaroids of people and places, then annotating the prints. He exists in an eternal present, a state amplified by the generic, timeless quality of the neo-noir Memento: an unnamed setting; generic locations (cheap motels, dive bars, and abandoned warehouses); the absence of digital technology; and stock characters (cops, barmaids, snitches, and dealers).

While reviewers raved about its challenge to traditional linear narrative, Christopher Nolan, who directed and scripted Memento based on a story by his brother Jonathan, admits in one of the Blu-ray extras (an interview that aired on the Independent Film Channel) that the film is “totally linear”, and that, because of the difficulty of following the story backwards, Memento includes multiple clues for viewers, more so than a conventional narrative. Another extra, an episode of the Sundance Channel’s Anatomy of a Scene dedicated to the opening sequence of Memento, explicates how the film introduces its unique narrative structure to the audience.

It’s really in the realm of character development that Memento most destabilizes cinematic conventions. In the Anatomy episode, in the IFC interview, as well as in a short interview with the director commissioned for the new Blu-ray edition (“Remembering Memento“), Nolan emphasizes Leonard’s inability to note the passage of time. As Leonard himself laments, “How am I supposed to heal if I can’t feel time”. He’s not. Caught in a perpetual now (or more accurately a perpetual “just after” with respect to the trauma that altered his life), Leonard is incapable of the changes that we expect of characters in a traditional film. Indeed, in the film’s more pensive moments, Leonard outlines how his disability prevents him from emotional or intellectual growth in lines that sound simultaneously like zen koans and country song titles: “I can’t remember to forget you” he observes with reference to his wife.

The film’s climactic scene sums up the threat Leonard poses not just to other characters but to character itself. In a sequence that packs a film’s worth of development into a few minutes, Teddy (Joe Pantoliano)—Leonard’s friend or nemesis (we’re never sure which)—suggests that Leonard’s version of the past is suspect: his wife may have survived the attack, and Leonard may already have meted out his revenge. The scene plays almost as a parody of plot movement—too fast, too late, too much—but in the logic of the film, Teddy has no choice but to wedge his explanation into the measure of Leonard’s short attention span: the brief time allotted to him in which to act on new information before his short-term memory resets.

For a fully intact Leonard, these unsettling assertions would no doubt have initiated a recognizable trajectory of development that would have been apparent in the early (that is chronologically later) scenes in the film. Instead, acting upon a kind of feral self-preservation instinct, Leonard, reduced to an automaton animated by the storyboard into which he’s converted his body, uses his tattoo notation system to program himself, like a computer virus (or perhaps more accurately, like the Manchurian Candidate), to “misremember” what he’s just heard, and act upon this faulty memory prompt later, with dire and probably undeserved consequences for Teddy.

The end of the film (its chronological beginning) thus explains its beginning (that is, its chronological climax), and suggests that the events we’ve just witnessed may mark only the latest in a cycle of successful revenge plots. Characters who can’t change are doomed to repeat their actions.

Memento shares a further twist with Nolan’s recent success Inception, another film in which a desperate man goes to extremes to keep the memory of his dead wife alive. Both films embody not only Nolan’s predilection for deploying alternatives to traditional narrative, but also his penchant for structuring the bulk of a film around a heterosexual romance plot, only to assert a countervailing same-sex friendship plot that overwhelms the first in a film’s closing minutes.

Inception follows the adventures of a team, led by Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio), who enter people’s dreams in order to retrieve secrets or implant an idea (the “inception” of the title). Cobb’s dead wife Mal (Marion Cotillard), formerly part of his team, has a residual presence in the dream world. Just as Cobb reluctantly decides to spurn his dream wife in order to rescue a male client in the final, and deepest subconscious level in Inception, so Teddy reveals in Memento‘s finale that he and Leonard have shared a long-term codependent relationship. The triumph of male camaraderie over the company of women is a plot bug with a long history in film and literature, from Jaws to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and looks to have a healthy life in the twenty-first century.

Lionsgate has billed the commemorative Blu-ray “an all-new director-approved high definition transfer”, and the excellent image and sound quality on the disc make good that claim. The interface is elegant and intuitive. The three extras mentioned above provide insights into the film and its production, although since two of them were produced independently, there’s considerable repetition. A gallery of Leonard’s tattoos, Leonard’s journals, the film script, and Jonathan Nolan’s original short story, “Memento Mori”, fill out the extras.