The poet, painter, novelist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau specialized in giving his audiences access to the interstitial space, the liminal realm, between dream and reality. His characters speak a language steeped in reverie. Every utterance is poetic, elliptical, and deeply cryptic. For Cocteau’s protagonists, the metaphorical replaces the denotative. This is the speech of indirection, of elusive allusion. Suggestion replaces content. The dreamer’s language points away from the objects at hand; theirs is a determinedly impractical mode of communication.

Indeed, communication seems beside the point. These characters fail to speak of their own accord; they possess no linguistic volition. Rather, language speaks through them. They’re not subjects employing language, but rather subject to language’s whims. It’s as though language itself seeks that one word that would break the spell, that would call a halt to its own outsized prolixity.

Cocteau recognizes that the true dream state is inherently restless. His dreams are always ill-at-ease, replete with malaise. His dreamers long to awake, and yet perforce they would linger in the subcutaneous realm of the dream. The dreamer wishes to pierce the dream, to plunge irrevocably through its barrier, but fears what’s on the other side. In the dream, language is a pure system of resemblances. A thought dissipates and gives rise to another. But this fluidity is deceptive. Each word is haunted by the specter of its own impermanence and falls into an allegorical array that threatens to calcify, to become a stultifying web that suffocates the dreamer.

Cocteau’s dreamers have a bad conscience. They move through their lives like somnambulists. Like somnambulists, they navigate their world with a preternatural confidence, an unfailing and unfeeling sense of direction, a paradoxically aimless teleology. They’re sleepers awake, beautiful but diseased. For Cocteau, beauty always involves sickness. The rose is most alluring, reaches its point of greatest redolence, as it decays. Sweet fragrance gently fades into pungency. Fair seekers seeking nothing and everything, Cocteau’s dreamers grasp at the nothingness that surrounds them. Dreams for Cocteau are fragile but pervasive. Every moment threatens their destruction; they constantly foreclose upon their own existence, and yet they remain stubbornly open, they persist and thrive in their own dissipation.

The liminality, the perduring ephemerality, that is Cocteau’s métier is precisely what makes it such a difficult subject for film, even when Cocteau himself was the director. The symbolic richness of the dream state can easily become cloying. What should be a cryptic gesture can become an overwrought bit of theatricality. Cocteau’s delicate beauty, imbued with a quiet horror, may devolve onto kitsch. The rarefied heights of the transient whisper may carelessly slip to the depths of grotesque banality. The trick, it seems to me, is the hold on to that other side of Cocteau’s dichotomy: that is, reality.

Cocteau’s imagination hovers within the realm of the irreal, and yet, it’s ever mindful of its purchase upon a quotidian, average everydayness. This is the hardest part of Cocteau’s work to comprehend and the easiest to overlook, or even to deny. Yet, it’s the vital element that allows his work to do the work that it does; this ever-slipping grasp upon reality is what forces his work beyond mere flights of fancy, beyond the fevered aspirations of imagination, and onto a plane of meaning that intersects with the ways in which we live our lives.

Despite his Wagnerian ambitions and obsessions, what’s miraculous about Cocteau’s work is the manner in which it reverses the Wagnerian paradigm. If Wagner transmutes a lived experience of love onto the mythological level of the universal, then Cocteau reduces transcendence to the quotidian. For Wagner, Tristan and Isolde, starting as earth-bound lovers compromised by the fraught circumstance of their social obligation, dissolve into a spiritual remainder, a surplus-value of a volitionless love, a love beyond desire, a love that cancels out desire; in other words, an impossible and symbolic love. Wagner seems to hold that love is cheapened by circumstance and thus for love to remain, reality must wither. Our reality is shown to be untruth. To access truth, we must demonstrate that reality is a lie and thus eradicate it.

Cocteau, at his best (and he’s not always at his best, of course), countermands this trajectory of transcendence. He starts with the transcendent realm. Love, contempt, honor, betrayal — all of the concepts to which language refers occupy an ideal, noetic, quasi-Platonic sphere. These concepts are eternal and immutable. Indeed, the term “concept” is misleading here because it implies there’s someone doing the conceiving. But for Cocteau, Love and Hate inhabit a supra-human and sempiternal identity. They are not merely the conceptual labels we employ to make experience fungible, but rather they are the foundations on which all experience is predicated.

Yet, these pure, static forms, in order to have any veritable existence, must of necessity become corrupted by our use and our experience. They must become exchangeable. The Wagnerian surplus becomes a medium of exchange. This partially accounts for the elegiac quality of Cocteau’s language. Its lyricism is partially ironic — not in the sense that it “doesn’t really mean what it says”, but rather in the sense that it’s aware that all meaning crumbles in the necessary transition from the ideal to the real. Language here points hesitantly beyond the real. It longs to connect with the ideal, with the eternal, with the transcendent. The poetic nature of Cocteau’s discourse is the poetry of failure and of collapse. This is why his characters often sound so desperate. They yearn to savor the elixir of transcendent possibility but know only the bitter taste of wretched futility.

But it is this degraded, fallen state of language, this traffic in the disenfranchised ideality of speech, that vouchsafes its efficacy. This is Cocteau’s irony. The originary value of the word lies in its ideal existence, its surplus value, but such value is meaningless in that it lies outside the circulation that would make it vital. To do work, language must move; the static ideal must perforce become the dynamic real. By falling into disrepute, language gains a foothold in meaning, in consequence. Wagner starts with the real, exposes it as a lie, and finds the truth in the ideal. Cocteau starts with the ideal, reveals it to be a bloodless lie, and makes reality a quest for some fractured, debilitated truth.

Film is, perhaps, the perfect medium to body forth Cocteau’s vision insofar as film is itself situated at the nexus of reality and illusion. Film, like the Schopenhauerian or Freudian conception of the dream, projects a phantasmagoric image, alternative to reality. The penetrating light of the movie projector casts its shadows, brilliant and alluring, onto a dream screen that enchants and entrains us. We are locked into a passive partisanship, just like in the dream. We observe as the sequences unfold, anticipating their movements, registering the shocks of the unanticipated. We invest ourselves in these images that we know not to be real. They’re just bits of light floating through particles of dust, flashing on a blank screen of possibility.

We are wholly independent, with no corporate backers.

Simply whitelisting PopMatters is a show of support.

Thank you.

On the other hand, as Walter Benjamin has shown in his celebrated essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, there’s a deeply documentary quality to film and to the photograph in general. The picture seems to show the real as it actually is. A photograph always seems to utter: “This is the way it is.” The photograph bears the stamp of reality. In a sense, the photograph is more real than real. Our experience only allows for the vestiges of reality owing to our ineluctable entrainment to the fugitive nature of temporality’s flux. The photograph arrests time, freezes it, insists that it endure. Through the dominating force of the photograph, we are able to glimpse reality in its stark rigidity, in its flat insistence on duration.

Film, of course, returns the photograph to time’s inexorable flow. Yet something of that rigidity remains. We might see through the filmic apparatus, to recognize the illusory nature of the images, and yet something of that “this is the way it is” quality persists. Theodor Adorno, in his famous essay “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception”, worried that this element of film’s mode of being was precisely what made it so effective as a form of cultural propaganda and social control. Film approximates the real so closely that the line between reality and illusion is blurred. Illusion colonizes the real so that mass entertainment becomes mass delusion.

What Adorno sees as a threat works to the advantage of Cocteau’s vision. The ideal is degraded to the status of the illusion of the real, the impenetrable haze of disconnection that pervades our existence. Film, perched precariously on the border of illusion and reality, the ideal and the quotidian, lays open the foundations of our compromised existence.

This balancing act requires careful handling, a cautious equilibrium between realism and poetic escapism. Arguably the finest example of a film that strikes this balance is not one of the many directed by Cocteau himself but rather one directed by a then-young and unestablished French filmmaker who would soon emerge as a dominant force in film — but not for the dreamscape he conjured on behalf of Cocteau but rather for his take on film noir. That director is, of course, Jean-Pierre Melville and the film, only his second feature film, is Les Enfants terribles (1950), based on the eponymous 1929 novel by Cocteau.

The Experienced Artist vs. the Ambitious Neophyte

Cocteau had been pursued for years for the film rights to his novel and was even offered to opportunity to serve as its director but he always refused, convinced that the novel would simply not translate to its advantage to film. But when he saw a screening of Melville’s first feature-length film, Le Silence de la Mer (1949), something inside him clicked. He was impressed by the deft handling of the film by the new director but more to the point, he was struck by the actress Nicole Stéphane and her remarkable resemblance to Cocteau’s own illustrations of the character Élisabeth from Les Enfants terribles. Cocteau was comforted by the fact that Melville, despite his inexperience, was fully in charge of his art. He was not only a director but also a producer and ran his own small studio. This would be a film that could fully realize its vision.

But that “it” was precisely what became the ground of contestation. Whose vision would the film exude: Cocteau’s or Melville’s, the experienced artist who has been celebrated for decades or the neophyte but ambitious director eager to test his directorial mettle? Thus, a contested collaboration was born and admirers of the film continue to debate just whose film this ultimately is.

The source of the confusion is obvious. Anyone who has seen Cocteau’s own directorial debut, Blood of a Poet (1930), or his The Eternal Return (1943) —

a retelling of the Tristan and Iseult legend that reveals Cocteau’s Wagnerian debts — will undoubtedly remark upon a certain concinnity of style shared with Melville’s Les Enfants terribles. The acting style, particularly of Cocteau’s adopted son Edouard Dermit but also of Stéphane, exemplifies the restrained angst and ironic melodrama Cocteau cultivated. Certain tableaux, including the shot of Élizabeth’s new husband’s corpse laid out on the hood of his automobile, could be spliced into nearly any Cocteau film without dissonance. Intriguingly, the latter scene was actually directed by Cocteau himself when Melville was too ill to appear on set but as Melville would later insist, Cocteau followed Melville’s written instructions to the letter. Moreover, the entire film is narrated by Cocteau; his voice suffuses the soundtrack, we are immersed in this world through the gently nasal tones of his speech.

Both Melville and Cocteau insisted throughout the remainder of their lives that this was Melville’s film but Melville often displayed a marked resistance to discussing the work. Furthermore, there are numerous tales detailing Melville’s resentment of Cocteau’s constant presence on the set. Cocteau coached the actors in their delivery of his dialogue and the actors came increasingly to look to the author for approval and advice, much to Melville’s chagrin. Melville, in a fit of pique, asked Cocteau to leave the set and to allow him to do his work, then recanted and invited him to return. Accounts differ as to whether or not Cocteau was involved in the editing of the film. Whether he was or not, the resulting job is certainly consonant with Cocteau’s approach to editing.

One can certainly understand the tensions inherent in a collaboration of this sort. Now a sexagenarian, Cocteau had been on the periphery or at the center of nearly every major art movement of the first half of the 20th Century in France. Active as a novelist, a poet, a playwright, a visual artist, a filmmaker, an impresario, and a provocateur, Cocteau was a man of nearly mythical proportion in his own time. Melville, on the other hand, was still struggling for recognition. Upon his return from the war, he applied for an assistant director’s license, but was flatly rejected. Determined to forge his own career path, Melville founded his own studio, becoming an independent filmmaker, and blazing a trail that would eventually lead to the French Nouvelle Vague. A luminary and a neophyte, they were bound to clash, despite their mutual respect.

There’s a sense, perhaps, in which this antagonism serves the material well. If, as a director, Cocteau tended toward the fantastical, Melville emphasized gritty realism. Therefore, since, as I suggested above, Cocteau, the writer, at his best, navigates the Charybdis of illusion and the Scylla of realism, then the combination of Melville and Cocteau here give rise to what is perhaps the most perfect realization of Cocteau’s vision on celluloid.

The film opens with a scene in the past tense. It’s not, however, a flashback. We are introduced to Paul (Edouard Dermit) as a schoolboy in the midst of a snowball battle, searching for the boy he idolizes, Dargelos (Renée Cosima). The scene is presented as the beginning of the story and as though we are sharing the temporality of the figures portrayed. To say it is in the “past tense”, therefore, seems arbitrary and perverse. Yet, we cannot help but detect a pastness in this scene, an ambience of time lost and irrecoverable.

This is a tableau, characteristic of Cocteau’s oeuvre, that wistfully declares its ephemerality and its importance as a marker of the irretrievable loss of meaning bound up in youth. Cocteau treats youth as the plenipotentiary of authenticity, the guarantor of meaning. To age, for Cocteau, is to be deprived of vitality, of the fullness of being. To grow old is to succumb to the meaningless remainder of existence. When Dargelos strikes Paul with the snowball in which he has hidden a rock and collapses Paul’s chest, causing the school authorities to send Paul home and excuse him from his scholarly responsibilities, we witness Paul’s expulsion from the plenitude of adolescence. Paul enters adulthood with an infirmity because adulthood is the condition of the infirm.

Melville shoots the outside scene, the snowball fight, with the lambent light of nostalgia. He registers this moment as occupying Cocteau’s prelapsarian domain. But in the very next scene, when Dargelos is interrogated by the schoolteachers and proves himself to be a contumacious brat, the light inside the room is harsh, garish. Its analytic precision replaces the gleaming phosphorescence of the snowy exterior shot. This scene, through its continuity with the previous one, perhaps continues in the past tense, so to speak, and yet it portrays a harsher reality. It leads us toward the present insofar as the underlying enigma at the center of the charm of nostalgia is revealed to be the cruel indifference of an adolescent bully.

The alternation of scenes captures rather well what worked so beautifully in this contentious collaboration between Melville and Cocteau. The point of the film is not to find some meeting place between the dream and reality, nor is it able to truly depict an interstitial realm that is somehow both and neither at the same time. That realm, whatever its level of existence, is simply not representable. What the film manages to do is to intimate this realm through a process of self-cancelling of both the dreamscape and the quotidian. Moments of poetic splendor are succeeded by flashes of bitter verism. Fantasy gives way to verisimilitude.

However, the magic of this film transcends mere alternation between the gauzy vision of the idealist poet and the incisive glare of the realist director. Take the final scene as our example. Paul has taken poison in his despair at not being able to attain his true love Agathe (also played by Renée Cosima). The source of Paul’s desperation is his sister Élisabeth, who deliberately misled Agathe to marry another and intercepted Paul’s confession of love. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Élisabeth will take her life as well and the siblings will leave this world together — a tragic ending poetic enough to point toward the universal and banal enough to comport with the real.

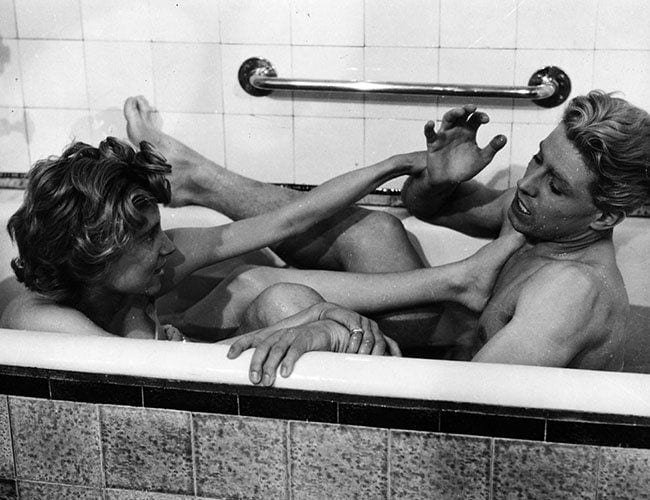

Cocteau wanted the final tableau to resemble one of his drawings: Paul and Élisabeth would lie side by side, their heads inclined toward each other, in the manner of an idealized Tristan and Iseult, united in death as the lovers they in many ways were but could never admit to being in life. Melville had a different idea in mind and ultimately, he prevailed. Élisabeth, seeing Paul breathe is last, hearing the death rattle, recoils from the scene and grabs a pistol. The camera jumps to the exterior of the screens that surround Paul’s bed. For a moment, all we see is the blank white of the screens and the silhouette of Élisabeth, gun to her head. Then the shot and she falls. She topples the screen and falls abjectly to the hard, cold floor. The camera looms above the scene: poetry and documentation at once.

Melville’s ending is superior not simply because it follows the poetically rendered scene of Paul’s demise, and not because it transcends the duality of poetry and realism. Rather, this final scene enacts the trajectory of descent that Cocteau’s finest work always traces. It’s not transcendence, but degradation. The ideal is lost, or rather it’s given up. Élisabeth’s death does not transcend reality but rather brings the ideal crashing down to earth where it sputters, writhes, and breathes its last.

Film Forum in New York City presents a Jean-Pierre Melville retrospective from Friday, 28 April to Thursday, 11 May. The festival features such celebrated films as Un Cercle Rouge, Army of Shadows, and Un Flic. Any of Melville’s films are well worth seeing and savoring but (obviously) there’s a special place in my estimation for Les Enfants terribles. If you can get to the Film Forum, I highly recommend you take the time to immerse yourself in this beguiling film.