Ten years ago, we began presenting the beloved Counterbalance series that ran through 2016. Jason Mendelsohn and Eric Klinger debate the merits of some of the most critically-acclaimed albums of all time. We are re-running the entire series with a new entry each Monday. Enjoy.

Mendelsohn: I have nothing bad to say about this album. Nothing. But I will suck it up and do my job as a critic and start critiquing. I have two words for you, Klinger: “Yellow Submarine”. Without Ringo’s dystopian little gem about a magical place where we all live in submarines and no one ever lapses into a claustrophobic rage, Revolver may very well be the perfect album. Prove me wrong.

Klinger: A bold statement, Mendelsohn, and one that’s awfully hard to dispute. But let’s take a Slate.com-like contrarian view here, if for no other reason than to generate some false controversy. After all, who doesn’t find the devil’s advocate delightful?

Even putting Ringo’s kiddie number aside, the individual songs on Revolver are actually kind of slight. McCartney offers up a soap opera melodrama, a pleasant little love song, a highly controversial ode to sunshine and a tune about weed. George bitches about having to pay taxes and messes around on a sitar. Lennon is the record’s MVP with two absolutely brilliant songs that would set the tone for the rest of the decade (“She Said, She Said” and “Tomorrow Never Knows”), but even he ends up writing a love song to his dealer.

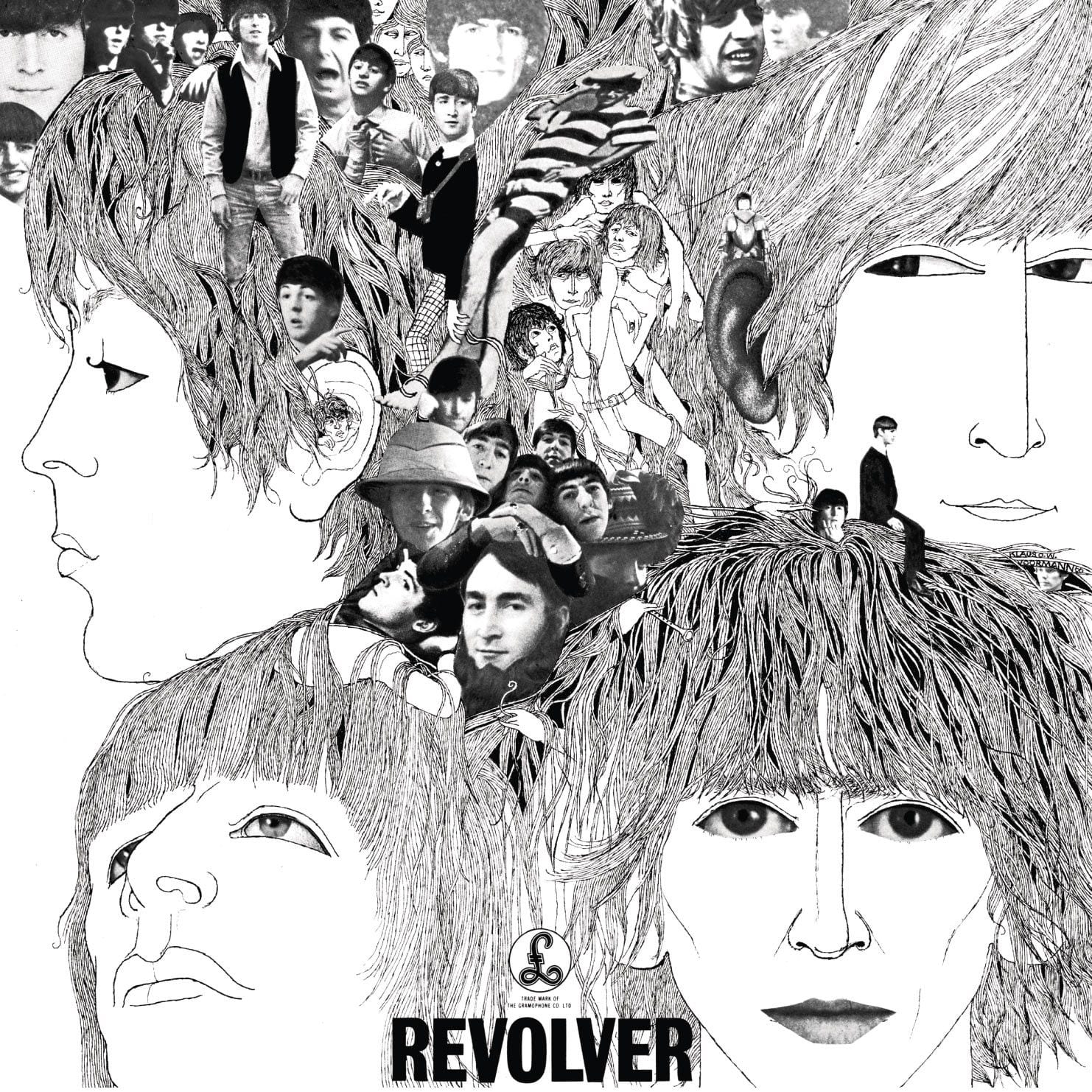

And I’ve never liked the cover, either. There, I said it.

Mendelsohn: Seriously? You’re going to attack the cover? C’mon, man. The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds features a photo of the band feeding goats (a serious WTF moment). Graphic design didn’t come into its own until sometime around 1976. And as much as I hate to say this, it was probably Boston’s self-titled debut that helped turn the tide. Not the album itself, just the cover.

Klinger: Those goats are highly symbolic, man.

Mendelsohn: Sure. But as for Revolver, who cares what the songs were about? This record changed the way albums would be made going forward. Multiple tracks, chorus effects, tape loops. The technical innovation alone is amazing. Of course, it was 1966, and the world had only just stopped being black and white ten years before. So make of it what you will.

Klinger: Well, furthermore… Aargh! I can’t keep this up! I don’t know how those contrarian guys at Slate.com do it!

Yes, Revolver is very nearly a perfect album. The Beatles, as innovative as they were, really excelled at synthesizing the various influences that were all around them, so they could incorporate Stax-ish horns, Byrds-like guitars, and baroque sunshine pop, and in the end it all sounds like the Beatles.

I first bought Revolver when I was 12 (I bought it at K-Mart!). It’s become so internalized in me that it’s hard to listen to it with new ears. But as I’ve revisited it in preparation for this piece, I’m really struck by just how much it rocks. The guitars have more bite to them than on previous Beatles albums, and the rhythm section is punchier as well. A lot of the credit goes to engineer Geoff Emerick, who may well be the unsung hero of the Beatles’ sonic evolution.

Mendelsohn: Sonically, this album is unmatched and a credit to the Beatles as true rock gods—not just mop-topped teeny bops. Thematically, this album is all over the map and while that could hurt a lesser band, I think the Beatles were finally realizing what sort of rock-body they possessed. If Rubber Soul was puberty, Revolver was young adulthood. Unfocused, energetic and brilliant, laying the groundwork for not only their future masterworks but for countless other artists and even whole genres.

Klinger: Agreed—despite my earlier attempt at satanic advocacy. The Beatles were coming into their own as songwriters, with Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison all digging in deeper and by extension pushing pop music forward. They did so not just sonically, but also lyrically. “For No One” is a keenly observed portrait of a relationship in its endgame, and the very idea of name-checking a sitting Prime Minister and opposition party leader (not to mention your dealer) pushes the boundaries of cheekiness in pop music. This was uncharted territory across the board.

I have to say, too, Mendelsohn, that this is a level of effusiveness I so seldom hear from you. It’s quite refreshing. What was your relationship with this album before this Counterbalance project?

Mendelsohn: Honestly, I don’t have much of a backstory with this album. Revolver came to me in a group package, along with Sgt. Pepper, Rubber Soul, the “White Album”, and Abbey Road, with little more instruction than, “The Beatles rock, man! Listen to these albums!” That’s a lot to get through. It’s taken me 15 years to come to the conclusion that Revolver, though a bit scattered, ranks highest for me in the Beatles pantheon. It seems that every musical road I’ve ever traveled down in my life has not only led back to the Beatles, but specifically to Revolver.

Pop and rock are the easiest lines to draw but Revolver also gave birth to psychedelia, thanks to “George messing around on the sitar”, and—more importantly for me anyway—the seed of electronic music, in both form and function, was planted with “Tomorrow Never Knows”. The 130 BPM, the obtuse lyrics, the tape loops—it’s house music for hippies.

I fell hard for electronic music when I was younger. We’ve since gone our separate ways—let’s call it a scheduling conflict—and while I’ve returned to my pop and rock roots, I will never forget those fleeting years of my youth spent behind the fader. It’s no coincidence that my two favorite songs on Revolver are “Taxman” and “Tomorrow Never Knows”, both rock out at the speed of house (the music, not the Hugh Laurie). I owe a lot to this album.

Klinger: I’d heard a bit about electronic music being shaped in part by “Tomorrow Never Knows”, and that’s a very interesting point. I think it’s also worth noting that as experimental the Beatles were getting by 1966, they were still first and foremost pop guys. Look over the songs again; the longest song is 3:02! “Tomorrow Never Knows,” with all its loops and noises and craziness, is in and out before three minutes are up. They knew the line between experimentation and self-indulgence—we’ll see if they’re still acknowledging that line when we get to Counterbalance No. 14.

I should also point out that the version I bought at K-Mart was the American LP, which cut three tracks to pad out Yesterday and Today. So it wasn’t until later that I finally heard “I’m Only Sleeping”, “And Your Bird Can Sing”, and “Doctor Robert”, and then not in the context of the album. Needless to say I had a somewhat skewed version of the Beatles’ development.

Mendelsohn: Speaking of skewed and “Doctor Robert”—is that song about acid?

Klinger: Perish the thought! The song is clearly about noted televangelist Dr. Robert Schuller, whose weekly Hour of Power broadcast was a huge influence on the Beatles. In fact, in 1968 the Beatles were on their way to a pilgrimage to Schuller’s Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California, when they got on the wrong plane and ended up in India. The Maharishi met them at the airport and never once corrected them when they called him “Bob”.

The ’60s were a strange time.

* * *

This article originally published on 16 September 2010.

- The Glorious, Quixotic Mess That Is the Beatles' 'White Album ...

- Re-Meet the Beatles: PopMatters Salutes the Still Fab Four ...

- The Magical Mystery Four: The Beatles As a Successful System of ...

- The Beatles 'Abbey Road' -- But Oh, That Magic Feeling, Nowhere to ...

- 'Revolver': An Admirable Look at Beatles' Evolution - PopMatters

- Counterbalance No. 1: The Beach Boys' 'Pet Sounds' - PopMatters

- Riotous and Hushed: The Beatles' 'The White Album' - PopMatters