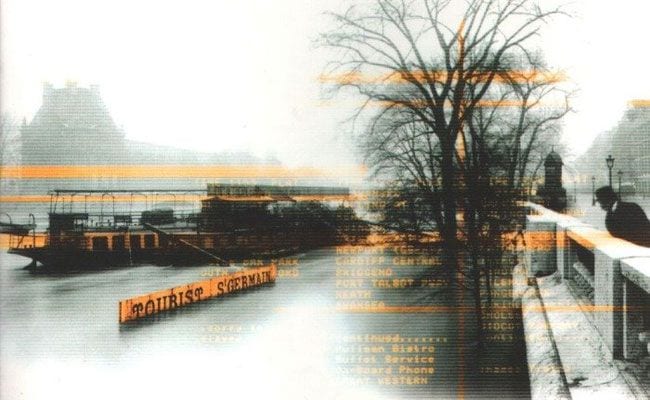

Mendelsohn: This week, I offer up yet another electronic album. This one is a little different, though, Klinger. It might be a little more to your liking. Or it might not. I don’t know. I’m not a mind reader. Although, I imagine you are going to tell me what you think because that’s how this works. So, I present to you St. Germain’s Tourist, a record from the venerated jazz label Blue Note, a record full of jazz soloing and blues noodling that just so happens to travel the speed of house.

St. Germain is the brainchild of French DJ and producer Ludovic Navarre. Navarre spent most of the 1990s releasing electronic music under various aliases until the mid-’90s, when he used the St. Germain moniker to start dabbling in laid-back groove-centric electronica, ultimately merging his electronic sensibilities with those of jazz musicians. The result was 2000’s Tourist, a record that sold over three million copies, garnered some critical acclaim (No. 41 for the year and No. 2971 all time) and helped sell out a bunch of concerts. But since then, Navarre’s output has dropped off completely. All we are left with is this record, a record that I think makes a real effort to merge two genres that are so similar yet decades apart. Does it work, Klinger? More importantly, does it work for you?

Klinger: You know something, Mendelsohn, I’m going to have to hold off on making a statement just yet. I need to know more. Because right now I’m hearing something that might be a cut above your standard electronic album, but it still gives me the same feeling as I get from most other things I hear from the genre. Yes, the jazz soloing takes Tourist in another direction, but no matter what I find myself checking the little clock on the player to see how much longer this track is going to go on. It’s that rhythm track, Mendelsohn—nothing happens.

In actual jazz, the rhythm section propels the song along, often in completely unexpected ways. The drummer probably doesn’t maintain a backbeat, instead allowing the bass to hold down the beat that centers the song. Here it’s a sample done up in standard 4/4 and a beat that seldom if ever changes. (That especially jarring to me when he samples Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five,” by the way, since that’s a song that’s pretty famous for being in 5/4 time.) Anyway, about three and a half minutes into each track, you’ll hear me say, “OK, I think I’ve got the gist of this,” and I skip ahead. But (and I feel like I say this a lot with these discs) talk me through it, Mendelsohn. Why did you pick this record? What is it you’re hearing that I should be taking note of?

Mendelsohn: I picked it because Tourist is one of those albums I pull off the shelf whenever I want some electronic music that moves, but isn’t simply limited to one guy pushing buttons and twisting knobs. Also, I’m trying to find to a way to slip you an electronic record that meets you half way. I have to tell you though, I’m not surprised by your reaction. In fact, as I was listening to this record, I thought to myself, “Oh man, I bet Klinger is going to find this record really boring.”

The Tourist doesn’t really stand up to the scrutiny of active listening for all of the reasons you listed above, especially if you are used to the free flow, improvisational spirit of jazz. I not sure if anyone, other than Navarre, thought it was necessary to connect cool jazz with Detroit techno but here it is. Maybe a little context might help as well. This record was released in 2000, a transitional zone for electronic music. Moby had spent the last part of the 1990s turning all of his music into car commercials and between the big beat of Fatboy Slim and the overproduced dance pop coming out of a myriad of boy bands and the like, there wasn’t much else to choose from. Enter St. Germain’s Tourist. This record isn’t a true gamer changer but it offers a different way to view electronic music and connect it to a genre that had fallen out of popular favor decades ago. As wins go for Blue Note go, this one was pretty big and fairly unexpected.

Just don’t listen to it as a jazz record.

Klinger: Well, that’s helpful, although the jazz soloing throughout is really what’s holding the record together for me. I think what keeps me from understanding electronic music is that I’m never entirely sure what I’m supposed to be doing while I’m listening to it. I’d rather dance to the more organic grooves of soul (it actually suits my, shall we say, unorthodox approach to dance). And what I’ve heard doesn’t seem to have the ebb and flow to hold my interest when I just sit and listen to it. With Tourist, I find it helpful to drive around and pretend I’m starring in a ’90s reboot of a ’70s cop show. That helps a bit.

And I keep coming back to a study I heard about where a scientician remixed a complicated piece of 20th classical music so that it more repetition in it and everyone, from average joes to serious music experts, rated their enjoyment of the music considerably higher. There’s apparently something in people’s brains that seeks out familiar sounds, so when we hear them our brain gives us a reward. There’s something in there that applies to both my situation and critics in general. Am I not accessing the part of my brain that seeks out these rewards? Is there something broken in my brain? Does my natural depressive state prevent me from receiving these rewards? Much to consider. Also does a person need to listen to something repeatedly to trigger that reward, which is why critics are so often wrong in their initial assessment of an album? Please answer these questions, or refer me to a qualified neurologist who can.

Mendelsohn: I listen to a fair amount of electronic music. None of it makes me want to dance. I’m not saying you can’t dance to some of it. I probably could but it would be a lot of flailing about and no one needs to see that. Let go of that stigma, Klinger. Just because the music is electronic doesn’t mean you have to be in the club to enjoy it. Yes, it is repetitive, more so than most music. But I don’t think it is any more repetitive than some forms of the blues. Blues out of the North Mississippi hill country by the likes of Junior Kimbrough and RL Burnside is borderline trance (and trance is just a faster version of house). Don’t dwell on the fact that some of St. Germain’s songs go on for nearly ten minutes, look instead at the how and why. Look for the subtle variations within the repetition as the flute gives way to the piano and back again.

Klinger: That’s certainly a different way of thinking about it, and it’s pretty much the same advice as you’d give to people who can’t wrap their heads around jazz or classical music. I think it’s the case with any unfamiliar genre that outsiders have a hard time distinguishing thought-out intelligent stuff from hacky crap, and it may be even more challenging when you’re talking about music that can sound flat-out boring if you aren’t keyed in. In the case of electronica, part of the problem may be that we keep hearing the word “dance” when people talk it, and that sets people up for unrealistic expectations — much like when Taco Bell uses the word “food” in its marketing.

St. Germain is clearly, even with my tin ear for this stuff, a good example of thoughtful electronica, and at some point here I’m going to get around to listening more closely for the nuances that make the difference.

Mendelsohn: There is an ebb and flow to this record, but it is on a much larger scale. When you are on the beach, the waves are varied and come quickly, breaking fast upon the shore. When you are out at sea, the waves are large and low, not nearly as pronounced as the boat rolls gently over each crest. Listening to Tourist is a lot like being out on the open ocean. It may all look the same, but that’s just because you’ve been staring at the sun and drinking salt water.

Maybe your brain just isn’t compatible with any electronic music. But as you noted, critics often respond in the negative to music they find unfamiliar before doing an about face once it has set in. Let this record set in, Klinger. It can be a rewarding experience.