Grounded in the rhetoric of purity and authenticity, country music in the USA is and always has been a strange and alluring mélange of myriad influences ranging from the Tin Pan Alley songs that enthralled the urban centers of the early 20thcentury to the African American ballads and blues that suffused the South to the Irish and British folk songs and reels that invigorated the musical life of Appalachia—not to mention the ever-burgeoning catalogue of newly written songs that bolster and transform the tradition. Indeed, despite the ideology of folk origin with which this music has so often been freighted, country music as a commercial enterprise (stemming from the first tentative phonograph recordings in the early 1920s) has always involved a precarious and at times discomfiting balance between tradition and innovation, folkways and technology, the conservative and the progressive.

Naysayers, of course, parody the genre as the province of white male hegemony, exuding a simpleminded patriotism and a wrong-headed (often racist) nostalgia for the clear-cut hierarchies masked as traditional values embodied by the antebellum South. This caricature (as is the case with most caricatures) is not entirely without a purchase upon some of what its object of scorn entails. As can be seen in the segregationist campaign of country artist turned Louisiana governor Jimmie Davis (equally renowned for his racist policies and his rendition of “You Are My Sunshine“) or the furor that arose over some rather mild criticism of G.W. Bush on the part of the Dixie Chicks, proponents of country music often marshal it forth as the reservoir of American values under threat by the ever-changing modern landscape. But to dwell on this (mis)use of the genre is to overlook its complex and rich history—a history involving a vexed set of relationships among various factions of musicians and fans, producers and marketers, the proponents of mass media and professional music critics.

Country music—despite the paucity of black and Latino faces among the ranks of its celebrated promulgators and despite the rather limited roles (until relatively recently) assigned to women—has, from its inaugural moments, been deeply impacted by the influence of black and Latin sounds and defined by its relationship to both its image of women and the ever-increasing reality of their direct participation within the development of this music. Much like the history of the US as a whole, country music’s story involves the uneasy narrative of exclusion and desire (and conversely, inclusion and disdain) mapped on to a developing set of sonic signifiers that continually run up against an identity crisis. Perhaps more than any other genre (and again we see a parallel with the political history of the US), country music over and again finds itself asking after the qualities that make it what it is.

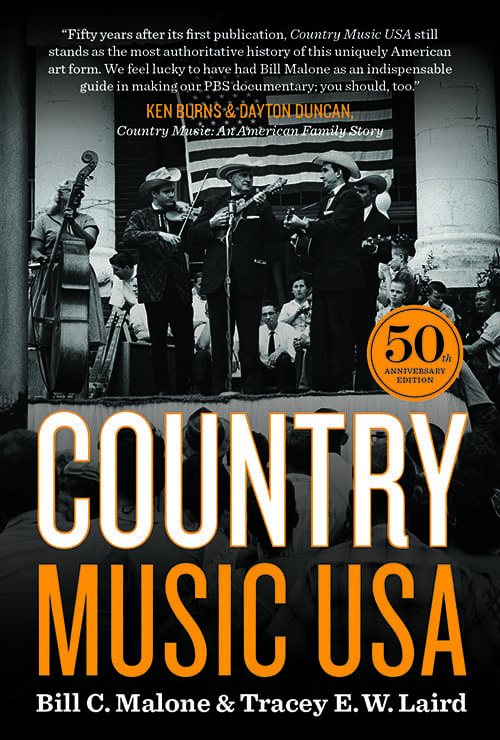

A long-standing guide to the twisting yet compelling tale of this music is now celebrating its 50th anniversary with a newly augmented edition. Bill C. Malone‘s Country Music USA has informed avid readers of the legacy of country music and launched the research interests of innumerable scholars. Malone tracks the narrative of country music from the scant information that survives from its pre-recorded era and the earliest recordings through the 20th century and the “new grass” revival of the ’90s. A new chapter by Tracey E.W. Laird closes the book by examining the perennial question “What is country music?” as it manifests in the first decades of the 21st century—exploring in particular the increasing dominance of hot country (Carrie Underwood, Brad Paisley), the alt.country-influenced acts on the fringes of the mainstream (Sturgill Simpson and Wheeler Walker Jr.), and the problematic nature of genre definition in an era of streaming and the decentralization of the dissemination of music as exemplified by Beyoncé’s country song “Daddy Lessons” and her performance alongside the Dixie Chicks at the 2016 Country Music Association Awards.

Laird’s contribution is a welcome addition to Malone’s celebrated tome but it also draws out the character of what Malone offers his readers. Whereas Laird concerns herself primarily with social trends and cultural issues (matters of definition and identity, the increasing if still marginalized presence of women, the problems with authenticity), these are largely peripheral concerns for Malone. Laird explicitly forgoes any attempt to provide a road map to country music in the 21st century but that is precisely what Malone so admirably assays for the 20th. In this sense, as fascinating and salubrious as it may be, Laird’s chapter feels as though it belongs in another book altogether—its delights are of a different nature than those on offer within the body of Malone’s volume.

While Malone hardly eschews the cultural and the social, he relegates these concerns to the sidelines. For example, it is only at the conclusion of Chapter 4, “Country Music during the Depression”, that Malone, almost apologizing for what he sets up as a digression, states: “Before ending this discussion of the 1930s and the transformations affecting the traditional music of the Southeast during that period, it is appropriate to explore further the economic context in which those changes occurred: the Great Depression” (151). Thus, in a chapter devoted to music during the Depression, the cultural, social, and economic context of that era plays a tertiary role, appearing almost as an afterthought, and largely to shift the focus to a discussion of Woody Guthrie, whose career was so thoroughly imbricated with that context. Malone resists offering a synoptic view of any of the various eras and trends he examines—indeed his only real attempt at providing such a view, in the largely unsatisfying opening chapter (“The Folk Background”), collapses under the weight of its generalizations, occasional contradictions, and lack of concrete data.

And yet, aside from that disappointing opening chapter, Malone’s book provides a veritable treasure trove of information regarding the musicians, musical styles, and distribution networks (primarily the radio and phonograph recordings) of country music. Indeed, the lack of the kind of historical contextualization one might expect from a book of this nature turns out to serve as a potential asset. Instead of historical categories and homogenizing accounts of musical trends, Malone presents his readers with discrete insights into the particular musical acts that gave rise to and perpetuated the country music tradition in all of its internal contradictions, negotiations, and accommodations.

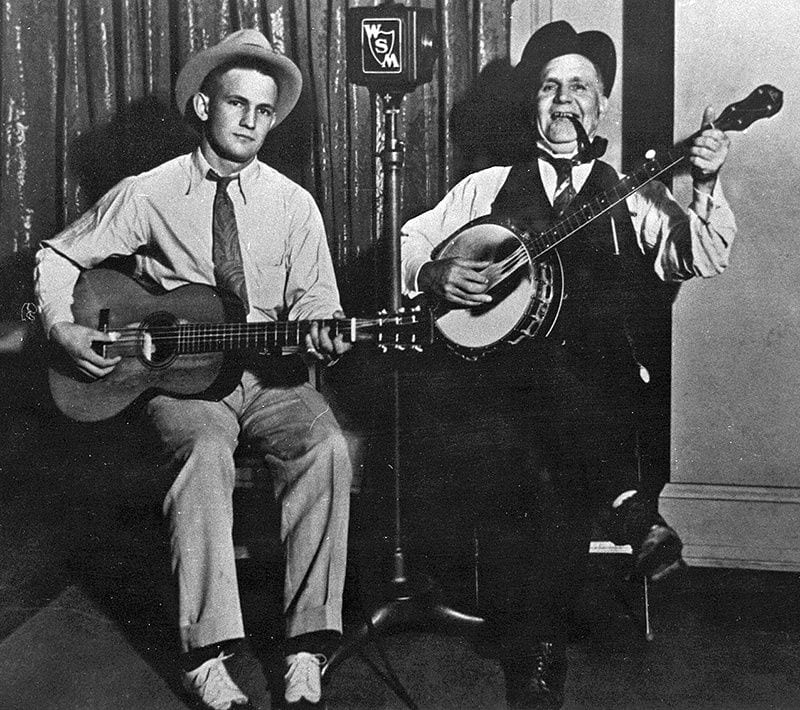

Of course, the narrative one expects to find is here. Ralph Peer (a recording engineer at OKeh Records who would soon become a producer, publisher, and talent scout) is surprised by the success of recordings of black blues and looks for other untapped markets to exploit; he is led by Polk Brockman (a phonograph store proprietor and talent agent) to Fiddlin’ John Carson. Peer is so turned off by Carson’s recording debut, which he memorably dubbed “pluperfect awful”, that he neglects to even provide it with a catalogue number. However, it sells remarkably well and Peer finds a world of relatively cheap recording artists opening up to him—culminating in the Bristol 1927 recording sessions (Peer is now working on behalf of Victor Records) that bring to prominence the two most important acts of the early phase of country music history: the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers.

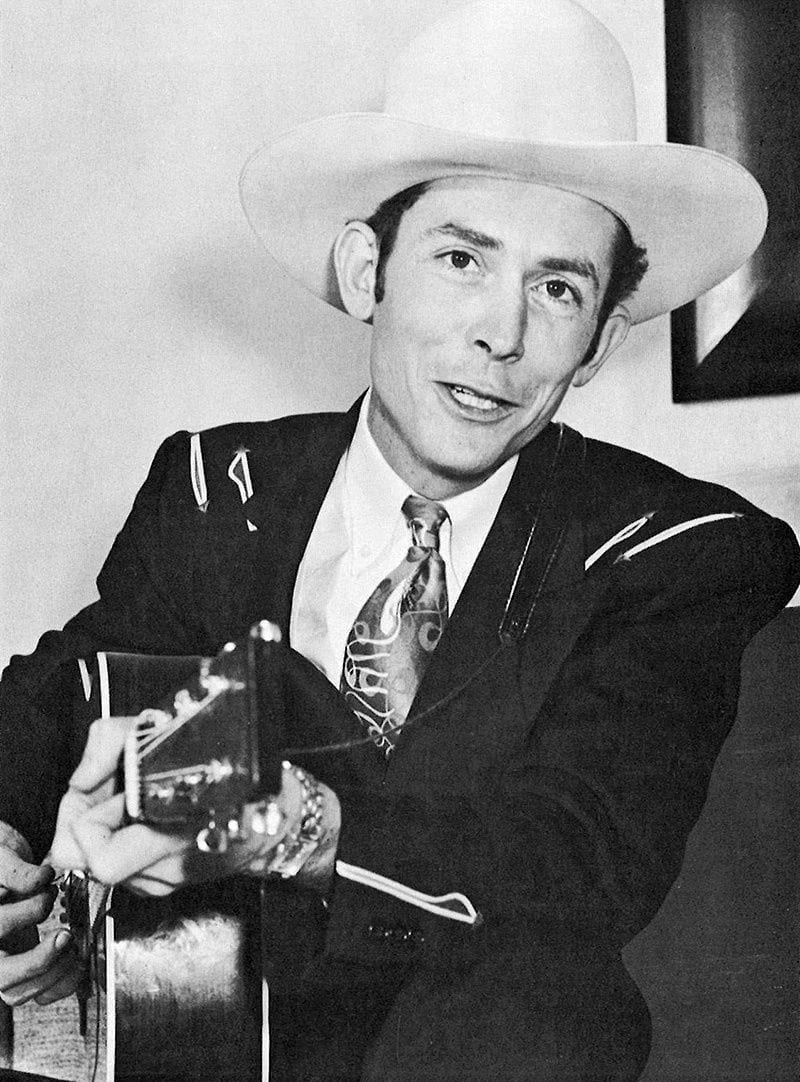

These acts establish the two main prototypes for the development of the genre. On the one hand is the Carter Family, featuring close harmony singing, presenting a wholesome and upright image, and highlighting Maybelle Carter’s innovative approach to the guitar (dubbed the “Carter Scratch” in which a melody played on the bass strings of the instrument is interspersed with chords). On the other hand is Jimmie Rodgers, the solo singer largely accompanied by his own guitar strumming (rather less sophisticated than Maybelle Carter’s), embodying the image of the rambling alcoholic—charismatic but unreliable—and standing out from other singers through his remarkable yodel. These two paradigms would shift and mutate over the course of the music’s history but the dialectic of the individual and the group, the sophisticated and the raw, the wholesome and the dangerous would come to inform the ethos of country music throughout the remainder of the century.

What is remarkable about Country Music USA, however, is not its telling of this rather familiar narrative—a narrative, of course, that this book did so much to establish and promulgate—but rather the sheer profusion of detail that emerges about the plethora of “lesser” acts that suffuse the music’s history. “Lesser” here does not indicate a measure of artistic merit, only a recognition that some of these acts are less recognizable today than many of the figures that serve as the main protagonists of the country music tradition.

With its concern for detail and its compendious knowledge of the overwhelming variety of performers, Country Music USA can be intimidating and, if improperly approached, may even strike readers as rather boring. After all, paragraph after paragraph roaming from one act to another can easily become ponderous. This book is best read slowly and with a streaming service at the ready. To merely read that the Dixon Brothers sported a “rough and sometimes-strident harmony” makes little immediate impact. But to hear the brothers sing together in their trenchant critique of the textile factories (in which they often worked), “Weaver’s Life” (1937), to experience the tremulous beating in one’s ears created by their gloriously stridulant vocal timbre and the affecting grind of their harmonizing, is to attain an insight into one region of a style of country music that had many variants in the Depression era.

This style is what Malone terms the “brother duet”. It often, but not always, featured actual brothers, singing in close (and often rather daring) harmony, and accompanying themselves on two slightly contrasting instruments. The Delmore Brothers featured a guitar and a tenor guitar; the Dixons employed a guitar and a steel guitar; the Callahans a guitar and mandolin. These groups drew on a wide swath of music for their material: blues, ballads, sentimental parlor songs. Certain duets incorporated some elements of jazz influence while others more closely approximated the rustic and the archaic. Most of these acts are forgotten today although certain of their songs went on to become established warhorses—Doc Watson performs an amusing version of the Dixon Brothers’ “Intoxicated Rat” and the Callahans were the first to record a version of “Rounder’s Luck”, better known as “House of the Rising Sun”. And, of course, the Delmore Brothers, with their smooth vocal delivery, sophisticated sense of harmony, and flawless performances had a notable impact on many subsequent acts even if the brothers themselves are not always brought immediately to mind when hearing those acts. To hear these brother acts directly is to open up a new vista of discovery and insight, to recognize a wellspring of creativity that transcends mere historic interest and taps into some hidden and forgotten mystery that still pervades the musical landscape of the US.

Malone’s book is replete with these opportunities for discovery. The narrative is shot through with remarkable artists like the white blues country singer Dick Justice (listen to his “Cocaine” of 1926), Clayton McMichen’s eclectic and daring Georgia Wildcats (check out the precise verve demonstrated in their 1937 recording of “Farewell Blues,” a tune cribbed from Benny Goodman), and Clarence White’s astonishing virtuosity. This is a book that one doesn’t read so much as consults, asks for recommendations for listening, peruses for insights into a music that sometimes seems so far away only to reveal itself to be right next door.