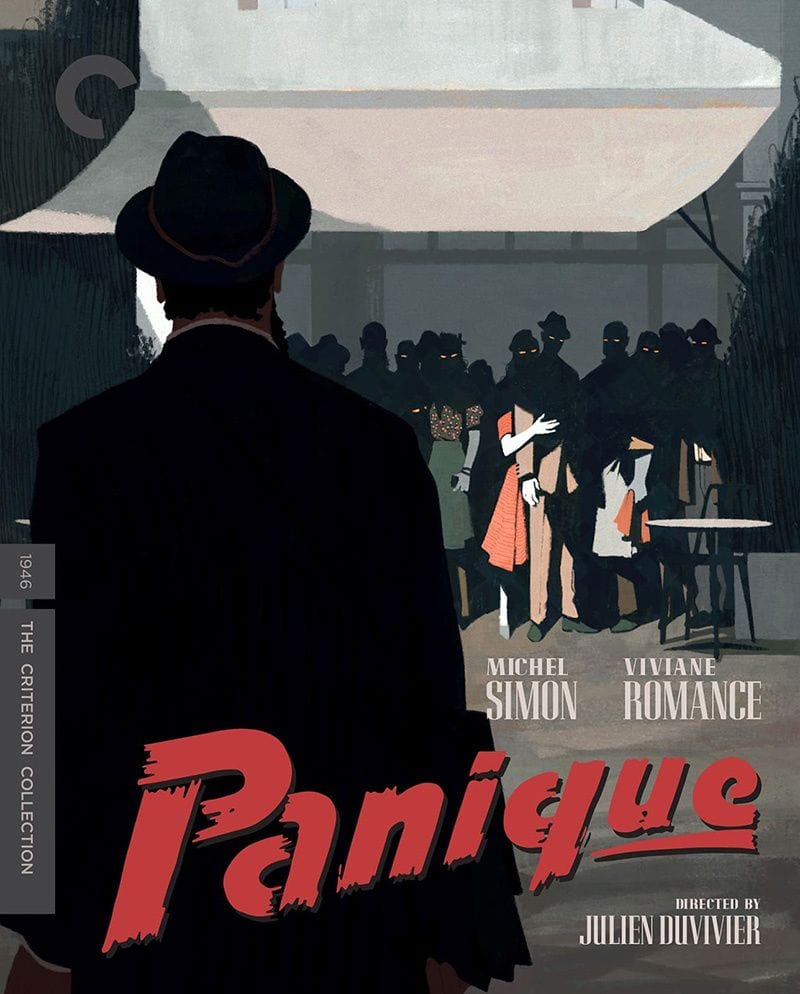

Panique (dir. Julien Duvivier, 1946)

The aloof and misanthropic Monsieur Hire (Michel Simon) appears to be a Jewish man who survived the German Occupation of France, perhaps because he masqueraded under multiple names in different locations. He falls into love or obsession with Alice (Viviane Romance), who has just been released from prison and rejoined her criminal lover (Paul Bernard). When Hire implies that the lover is responsible for the murder of a neighborhood woman, Alice must decide what to do. The rest of the film involves a plot to turn the whole neighborhood against Hire by playing on people’s suspicions, and the film becomes a bleak indictment of French communal mentality.

Director Julien Duvivier and his co-writer Charles Spaak adapted a Georges Simenon novel, later filmed more faithfully by Patrice Leconte as Monsieur Hire (1989). They changed and added many elements in order to provide a grim postwar commentary, shot in 1946, on scapegoating and hypocrisy. It wasn’t well received at the time, partly because nobody wanted to hear such things and partly because Duvivier had spent the war in Hollywood, so they thought he had little authority. As time has passed, the tour-de-force nature of the film’s many set pieces, including the frenetic bumper-car scene, the stairway expressionism, and the majestic crowd scenes, has only commanded more attention, and the technical brilliance is on full display in this 2K digital restoration.

One potential problem lies in the early sequence of the body’s discovery. Everyone appears to have poor eyesight at discerning what the viewer sees plainly: a pair of shoes still on the victim’s feet. One man uses a lamp to approach the corpse and decide it’s a woman, finally announcing her identity to the crowd. All this in what seems to be broad daylight. Then when the police arrive, it’s suddenly night. Have they taken all day to arrive while the crowd stood there, or have the previous scenes been printed without the proper night grading? That would explain a lot.

In an extra, two French critics point out provocative visual similarities to Alfred Hitchcock’s later films Strangers on a Train (1951), Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958). There’s an interview with Simenon’s son Pierre, discussing his father’s wartime experiences. A tangential bonus discusses the history of how foreign films have been subtitled in the U.S. James Quandt’s liner notes mark this film’s crucial connection between France’s 1930s poetic realism, especially Marcel Carné’s Port of Shadows (1938), and postwar French noir.

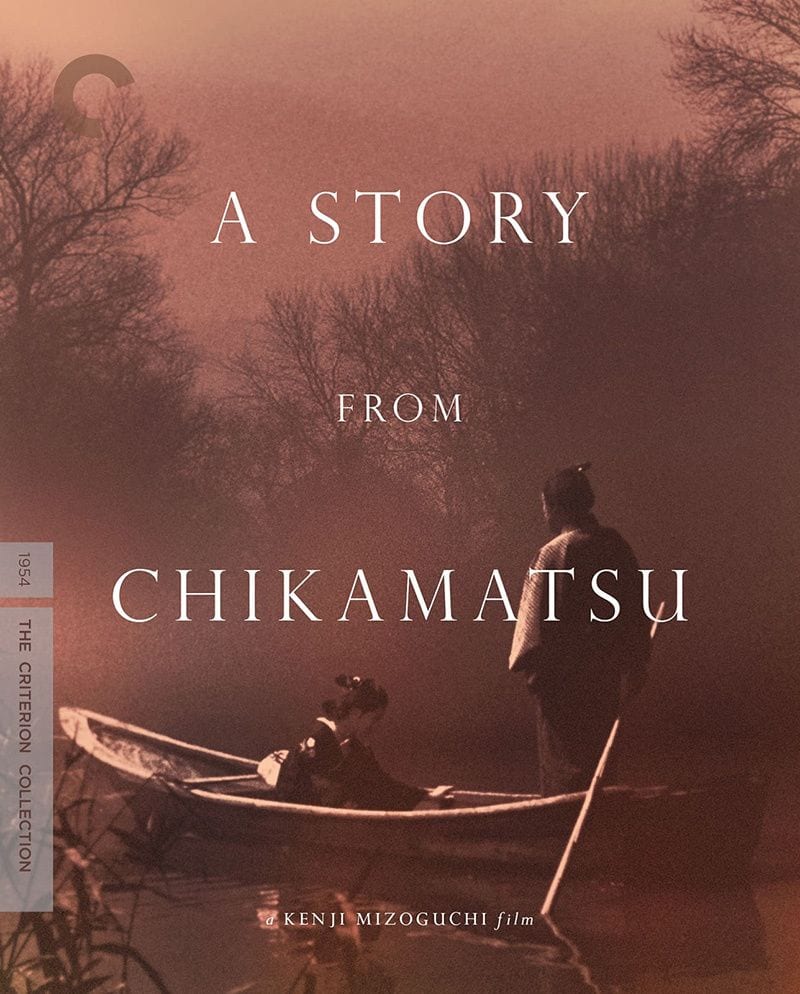

A Story from Chikamatsu (dir. Kenji Mizoguchi, 1954)

Chikamatsu isn’t a town but a man. Chikamatsu Monzaemon, who died in 1725, is Japan’s most famous playwright. He specialized in puppet plays (bunraku), many of which are about lovers who commit suicide or get crucified for adultery. This film, also known in the West as The Crucified Lovers, transfers one of those puppet plays to live actors. Everyone suffers because of a scroll-maker disliked by everyone.

His trophy wife (Kyoko Kagawa) gets caught in a compromising situation with an apprentice (Kazuo Hasegawa) and, instead of committing suicide for their honor, they fall in love and commit to staying together no matter what. This becomes a personal act of defiance within a culture of power and hypocrisy aligned against them.

Of all major Japanese filmmakers, Mizoguchi is the “Japanesiest”, if you will. Embedded in his nation’s literary, theatrical and artistic culture, his films find characters who glory in suffering and sacrifice, especially tragic women, in ways that ironically expose the problems in cultural traditions. When polished to crystal clarity, as in this 4K restoration, the films show his geometric medium-distance style of staging and cutting, with many examples of long-held takes amid atmospheric settings.

This movie has famous sequences of the lovers on a small boat (on a soundstage) and a majestic crane shot that cuts from a real hilltop locale to a studio forest. When the lovers escape from the confined elegant houses into nature, Kazuo Miyagawa’s photography becomes gorgeous, even when they’re just bedding down in a chiaroscuro shed. The music employs traditional bunraku style of shamisen, flute and percussion sticks.

Dudley Andrew’s audio essay does a good job of explaining the filmmaker’s style and influences in this film. Actress Kagawa (also a major star for Yasujiro Ozu and Akira Kurosawa) discusses how he tended not to direct actors, which often required many rehearsals until he was satisfied. She recalls that when rehearsing the scene at the bottom of the hill, she fell accidentally and he told her to use that in the take.

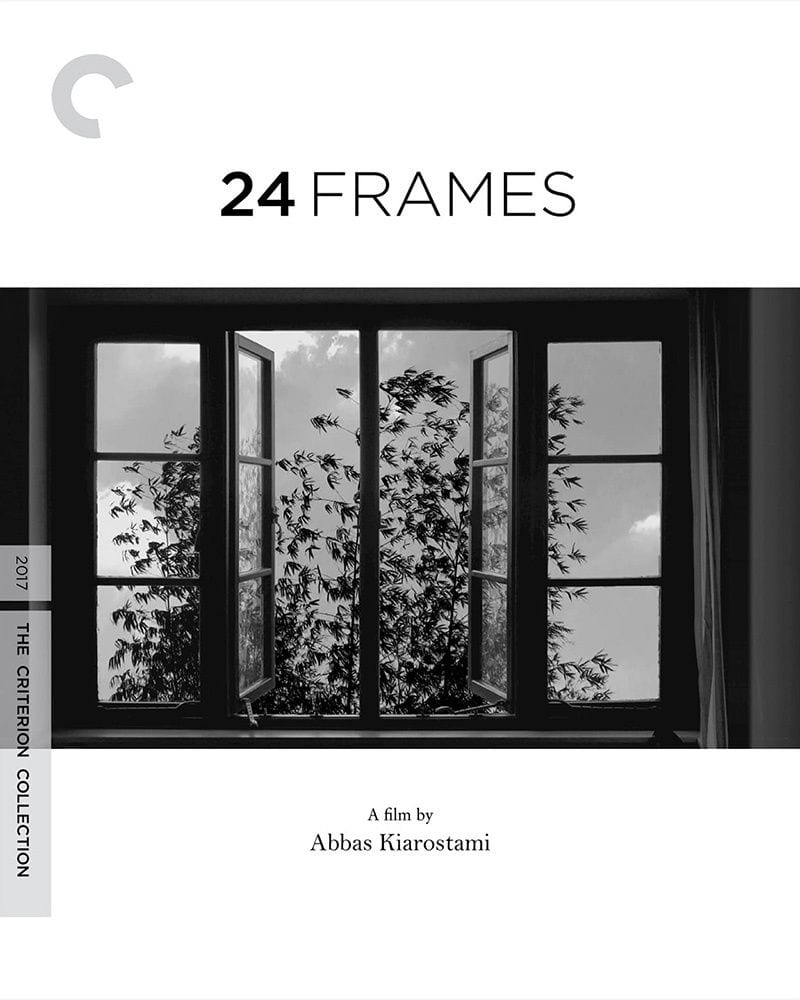

24 Frames (dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 2017)

What happens in this lovely film? Nothing. Originally conceived by Abbas Kiarostami as a multi-screen museum installation, this is a formal experiment based on the notion that you might stare at a painting or a photograph for five minutes, imagining the world inside it. That’s what Kiarostami does in these 24 short pieces, which are like photos that happen to be moving. The first piece is a painting: Pieter Bruegel’s The Hunters in the Snow, which becomes animated by certain moving elements: smoke, birds, dogs.

The other pieces are photography, many in black and white, that feature nature and animals. It’s often snowing or raining, and there are many birds and cows. We may intuit tiny dramas if so inclined. Sometimes a watcher is implied. Many pieces feature “frames” as in windows, gates and other shapes that divide the image. Frame 15, one of the few with people in it, combines a still image of people’s backs as they stare from a bridge at the Eiffel Tower and pedestrians pass between them and the camera.

Most pieces are marked by meticulous natural sound design, though a few feature songs like Maria Callas’ rendition of “Un bel di vedremo” and Janet Baker singing Gounod’s “Ave Maria”. The most complex piece is the final one. As we hear Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “Love Never Dies”, we see misty winter trees outside a window while, in the bottom foreground, a boy or girl sleeps at a desk and a laptop shows a slow-motion kiss from William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Many meanings can be read into this rich arrangement.

There’s a good reason this film hasn’t been on disc before: it’s new, the final film of the late Kiarostami. As the making-of clarifies, these pieces are highly constructed digital fabrications, full of cuts and pastes and tweaks, and not mere examples of planting a camera in front of a real scene for five minutes. Despite their concentration on the natural world and the seeming withdrawal of the director, his fingerprints are all over these meticulously elaborated tableau-poems.

In an interview, Kiarostami’s son Ahmad explains that he selected the 24 pieces out of some 30 prepared by his father, leaving out all but one of the paintings. He mentions a Picasso and Van Gogh, and the making-of shows us delightful glimpses of Millet’s The Gleaners, Rockwell’s Christina’s World and what appears to be a Vermeer.

He also says his father expressed the opinion that it was okay for viewers to nap during this contemplative visual album, as long as something of the film remained with them afterwards. Thus, as Erik Satie composed “furniture music” and Brian Eno created soundscapes that one could hear without paying attention, Kiarostami advanced into cinema that one might absorb in one’s sleep. Ahmad echoes what many reviewers have said, that this isn’t the ideal introduction to his father’s films, but for those already immersed in his work, it makes sense as a culmination of his artistic interests.

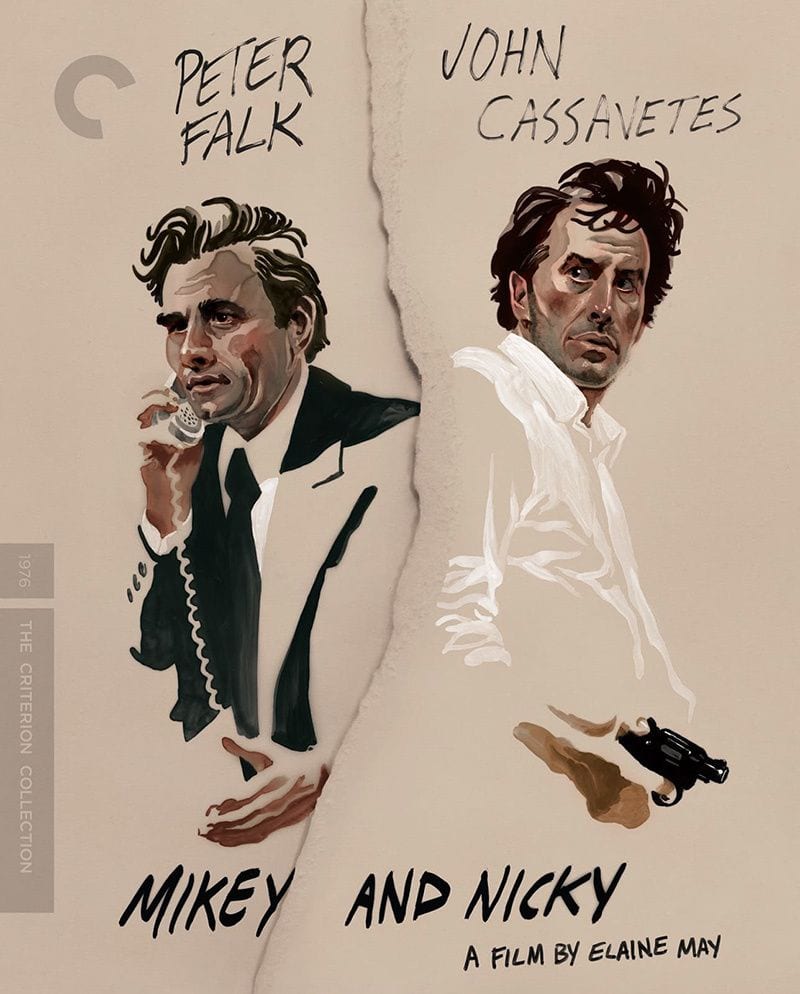

Mikey and Nicky (dir. Elaine May, 1976)

Desperate and afraid that a contract has been put out on him, small-time hood Nicky (John Cassavetes) calls his best pal Mikey (Peter Falk) for help, launching them on an all-night odyssey of encounters, confrontations and a tilt-a-whirl of emotions, recriminations and memories. These are unpleasant people in an unpleasant world, and it’s revealed in the first reel that Mikey is betraying Nicky and that Nicky suspects as much. This creates a harrowing sense of suspense and fatality as they spend the night wandering the circles of their private hells.

A nebbishy Ned Beatty plays the hapless hitman hired by Sanford Meisner and William Hickey as the gangster bosses, while painful women’s roles are etched by Joyce Van Patten, Rose Arrick and Carol Grace (wife of Walter Matthau, who starred in May’s 1971 romantic murder comedy A New Leaf). M. Emmet Walsh plays a pugnacious bus driver.

Although it feels like one of Cassavetes’ semi-improvised films, this grim anti-buddy movie of volatility and tenderness was a decades-long personal project of writer-director Elaine May, who was famous for comedy. She first discussed it with Falk when they met in 1967, before Falk met Cassavetes, and it was Falk who brought the latter in after Cassavetes used him in two of his own films. Shooting finished in 1974. After an antagonistic lawsuit-ridden relationship with Paramount, replicating her earlier experience with A New Leaf, May achieved final cut but the picture was barely released.

When I saw the VHS in the ’80s, it struck me as among the greatest, most vital and devastating films of the ’70s. Rewatching 30 years later, I wonder if I underestimated it. Darkly funny and discomfiting, with every scene adopting a disorienting tone that leaves you wondering what could happen next, the movie now feels like one of the best American films of the 20th Century’s last quarter.

At May’s request, this 4K restoration doesn’t remove any grain, and the opening shots especially look grainy as hell, as though we’re sharing Nicky’s petrified hangover. Victor J. Kemper shot the night with maximum grit and spontaneity, while Lucien Ballard shot the palpably different “dawn” ending. Extras are a brief making-of that largely avoids the troubled post-production, a discussion from two critics, and a 1976 radio interview with Falk.

The Criterion Collection, the busiest and most prestigious of companies devoted to classic films, provides a rare delight in this collection of films now available on Blu-ray. These are movies that have never before been on DVD or Blu-ray (at least not in Region 1), and in some cases weren’t even on VHS. These tantalizing titles, long heard of but vexingly unavailable until now, are a particular pleasure to for film lovers to enjoy, at last.