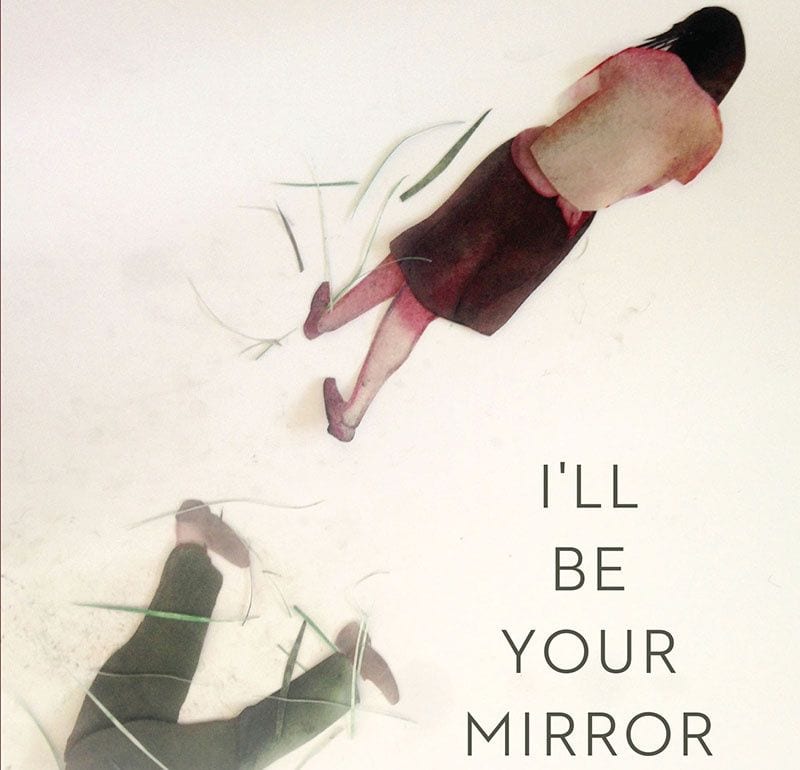

Sometimes intentional juxtapositions are a fantastic, powerful way to present a collection of linked literary ideas. Other times, they’re a miserable failure, a painful attempt to find a spot in the often slippery world of creative nonfiction. David Lazar’s I’ll Be Your Mirror: Essays and Aphorisms falls solidly in the former. The essays are presented in three parts: “Brigadoon Bowling”, “To the Reader, Sincerely”, and “Hydra: I’ll Be Your Mirror”. The Aphorisms, in a section called “Rock, Paper, Scissors, God: Aphorismics” (one heading takes the section’s title, and the other is called “Mothers, Etc.”) are a series of hit and miss one-liners that comprise the final third of this book. These aphorisms are accompanied by silky, disturbing, comforting drawings from Heather Frise. This mixture of prose, visual beauty, ,strangeness, and serious academic discussions of the narrative form clashing with touching personal recollections and just simple humor (especially in the Aphorisms) makes for a distinct reading experience.

Discussing form and intention is essential when considering the past, present, and future in the field of creative nonfiction. What was it? Where has it been? What is it doing now? Where should it go tomorrow? If the opening section (“Brigadoon Bowling”) works best, it’s probably because we’re more comfortable with the confessional format, more familiar with a writer trying to make sense of something profound, such as a loved one’s suicide, as in “Ann: Death and the Maiden”. Lazar begins this essay in June 1994. He’s watching the infamous OJ Simpson slow-speed White Bronco car chase as he recalls the death of his lover. The affair had taken place many years earlier (between Lazar, a 37-year-old professor, and Ann, a 34-year-old Doctoral student.) For Lazar, remembering her death was (and perhaps remains) a question of purpose:

“Why am I writing about Ann? Why am I thinking about Ann? Guilt is a privilege of the living.”

In the end, he discloses feeling responsible for her death; he’s still riddled with questions about what could have been done. “Who can rewind and untangle the currents of necessity and self-determination?”

In “Pandora and the Naked Dead Woma”, an essay that ends the first section, Lazar returns to the subject of collections and collecting. He refers to the collection of letters that he has stored in boxes over these many years, letters he’d written and received. This compulsion to collect material is a common affliction for those who observe, write, and ponder, and Lazar ponders it in remarkable ways:

“Sometimes I shed a tear, and a tiny little box falls out of my eye with paper clips and ephemera spilling out of the top. I never manage to get it back in.”

There are more questions, more considerations, and Lazar wisely allows them to dominate this consideration of why we save, what we save, and the role of tangible things in our lives:

“If memory serves me. Does memory serve me? How does memory serve me? When does memory serve me? When does memory fail me?”

The blessings of music hover over two major essays in this first section. As hard as it is to write about art or photography, it can be even more difficult to write about music. “When I’m awfully low: On Singing” and “Lollipop is Mine” are the jewels here. In the former, Lazar writes about earworms, those melodies that squat in major spaces of our brains and refuse to leave. For Lazar, the masters of the American songbook (Gershwin, Sondheim, Rodgers and Hart, and others) hold equal space with writers like M.F.K. Fisher and Charles Lamb. It’s “the tenacity of musical memory,” as Oliver Sacks put it in his book Musicophilia and the musical force is strong with Lazar.

“I liked to sing the song “Where is Love?” [from the musical Oliver] in my wan boy soprano, and my parents trotted me out at some parties to sing it, my mother beckoning me to sing the song of a boy singing for his lost mother…”

In “Lollipop is Mine”, Lazar takes us to his life in Syracuse, as a grad student over 30 years ago, studying with Raymond Carver and Hayden Carruth. Lazar takes us from his preoccupation with the doomed idealism of folk star Phil Ochs (who hanged himself in 1976 at the age of 36) through the power of doo-wop. “I mean, Dion was practically a saint in my neighborhood in Brooklyn…” That the combination of African-American and Italian heritage build two very distinct styles of doo-wop is nicely detailed here. The epiphany he notes at the beginning comes to fruition at the end of this beautiful essay, when as an adult he breaks down in tears hearing the Chordette’s “Lollipop”, a classic bubble-gum song with deceptively resonant meaning:

“…the sound felt new, and the effect was transporting. That’s what mattered most…popular music was sacred music… ‘Lollipop’ was just ‘Ave Maria’ with a bandwith.”

“Brushes with the Great and Not So Great” takes us through childhood encounters with singer Perry Como, actor Zero Mostel, and Dick Van Dyke. Lazar’s father was a travel agent and one of his clients was the notorious lawyer Roy Cohn, who was Lazar’s ticket into the legendary Studio 54 in the ’70s. “I loved sitting next to Valerie Perrine,” Lazar writes. “She was really friendly and would sort of rub up against you.” Film director Michael Powell, British music legend Richard Thompson, and American folk legend Pete Seeger all make appearances by the end, and the effect is strong. Rather than dropping names, Lazar equalizes them. He brings these stars into his radar screen and makes us imagine what would happen if we stumbled into greatness (however that’s measured these days.)

“Brigadoon Bowling” elevates the usually staid sport to mystical levels. “Bowling and writing are connected to me most viscerally, and if bowling was the release for my anxiety throughout my childhood… it was also the occasion for a crisis in which I first took writing seriously.” He had lost weight, found a purpose in this sport, and in the very title of this essay we get the sense of an ideal land. Brigadoon was the Broadway musical featuring a land where everything was perfect and everything stayed the same. “If anyone knows of a pretty little alley close to the city… I’ll go there alone, go through my paces, knowing I still know the steps.”

The title essay of the “To the Reader, Sincerely” section, and “Meet Montaigne (With Patrick Madden)” both deal with the role of the essay and how Michel de Montaigne has loomed over the form for many centuries. “At the end of his invocation ‘To The Reader, ‘…Montaigne bids farewell…he has urged the reader to not read his vain book of the self, his new form: the essay. He is also bidding adieu to the pre-essayed Montaigne.” “Meet Montaigne! (With Patrick Madden)” is a more concise, capsulized look at the writer. It’s written in the form of an interview. Why do we know him? What do we not know about him? It was written for a volume in which contemporary essayists covered the Master, and it keeps with the idea of dialogue, communication between the ages that is meant to never stop. Add “A Conversation with Robert Burton, Author of Anatomy of Melancholy (1621)” to the essays about essays and essayists, and the effect is enriching and academic without being ponderous.

“Being a Boy-Man” is a humorous interlude in this section that opens with a great line: “An ex-girlfriend used to call me her lesbian boyfriend, and this used to please me, flatter me.” If gender is fluid and subjective, Lazar seems to be at peace with that. “I’d like to define my gender as Fred Astaire, actually,” he writes, and the description is apt. Gender dances, evades, lives within what he calls “feminine outlines”.

The other essays about teaching and producing non-fiction writing, about essayists, “Hydra: I’ll Be Your Mirror”, “The Typologies of John Earle”, and especially “Voluptuously, Expansively, Historically, Contradictorily, Essaying the Interview with David Lazar and Mary Cappello”, run the risk of weighing down the tone of this book. They’re strong, compelling, and incisive in their observations, but perhaps most suitable for a student of the form, not a casual reader. Their greatest strength is demonstrating the scope of Lazar’s talents, interests, and commitment to the form. Especially in “The Typologies of John Earle”, the reader (experienced or not) is enriched by this discussion of our tendency to always use a basis of similarity to place things in categories, types, classifications and divisions:

“And I think in the essay much of what we do is both create and resist typologies, perform an inner and outer dialectic between our desire to narrow the possibilities and understand things better and the desire to not narrow them too much, to keep them open…”

The “Aphorisms” section of this book range from humorous one-liners (“The newest research suggests we should start licking our wounds like cats”) to profound (“Some blood is thicker than water”). Of course, Lazar’s master plan in presenting this collection of Stephen Wright-style aphorisms might have been to compel his readers into creating a master typology. The “Mothers, Etc.” section of “Aphorisms” is perhaps more dramatic and purposeful than the others, and Heather Frise’s illustrations (especially for the line “She had heard that blood was so good for the skin, that Mother”) are beautifully brutal.

The reader may leave Lazar’s I’ll Be Your Mirror: Essays and Aphorisms enlightened, thrilled, frustrated, and bewildered. If the heavily academic essays seem to carry more of the weight than those in the other sections, let them settle for a while. Lazar manages to entertain, draw the reader to hear his perfectly constructed pop song, and always remind us that there are others out there, other forms and perspectives, different ways to sing the harmony. As is, this book is a remarkable look at the transformative and thrilling “sounds” the essay can make when given the chance to play as many different instruments as possible.