There has never been anything calm and particularly concrete about images produced by film director and disturbing visionary David Lynch. From his 1977 feature film debut Eraserhead through to the 2017 Showtime TV revival of his classic TV series Twin Peaks it’s all been about darkness and visions seen through the haze of smoke, the gaze of obsessions, and the slow burning potential of destruction beneath both bright landscapes (Blue Velvet) and the kabuki horror whiteface of actor Robert Blake (Lost Highway).

Lynch takes his time, builds scenes through the flimsy patina of complacent conformity, and the fear of what isn’t seen becomes that much stronger when it is. Indeed, Lynch’s focus seems to have always been about forms and figures either from a distance through the mist or uncomfortably close. Plots are illogical and non-linear as they take a back seat to mood, atmosphere, and objectification.

Nothing within the definitive frames of Lynch’s lens can really exist autonomously, especially his women characters. From the disturbing scene in 1986’s Blue Velvet of a fully nude Isabella Rosellini walking down the street, arms stretched out as if she’s being crucified, to the graphic sexual trysts between two disturbed characters (Naomi Watts and Laura Harring) in 1999’s Mulholland Drive, the women in a Lynch film are dark creatures that use or get used. Even when they’re apparently free agents, their existence seems to be dependent on meeting the needs of the mood.

A viewer who buys a ticket on a David Lynch mystery train understands that women are always going to be his disturbing muses. Their beauty is prominently displayed through smeared thick lip gloss and what seems to be deeply medicated gazes into our eyes. We view with the understanding that we are voyeurs, intruding on their privacy, imposing our demands on a privacy they knew would never really be theirs. A David Lynch woman is never naked, never stripped of modesty and involuntarily forced into the spotlight. She embraces her nudity because she knows that in David Lynch’s world she will never have distinct individuality.

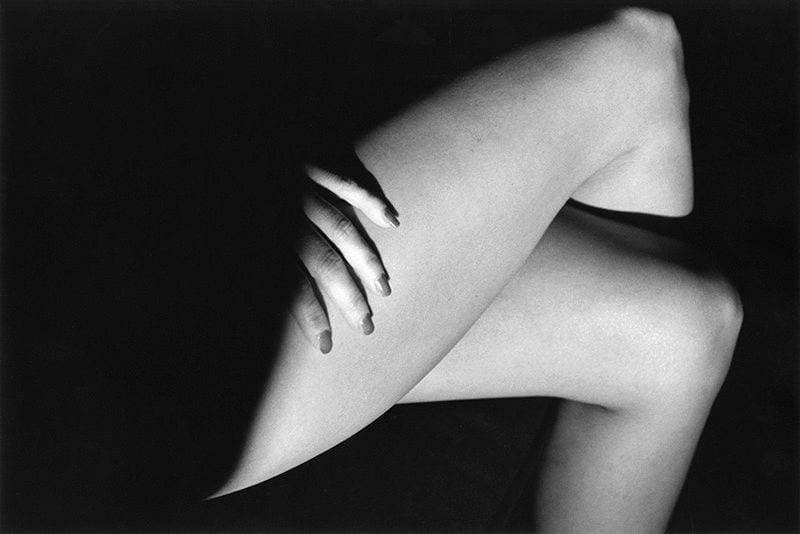

In David Lynch Nudes, the viewer needs to understand that images are the text. Lynch has not offered any background to guide us through the 240 pages, 125 black and white and color images. He offers three sections here, the color pictures sandwiched by the more complex and striking black and white. In color, the nude portraits of women’s faces are adorned by glossy lipstick that almost seem as if the color will smear on your hands if contact is made. In black and white, some of the women look like Theda Bara, or a Stieglitz portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe. They are lounging on couches, staring at the camera — at us — through clouds of cigarette smoke, burdened by the power of the multiple shades of grey. Most of these pictures are either close-ups of faces so distinct that their pores seem to be pulsating, or they are abstract and indistinguishable as anything easily identifiable. The few full-bodied nudes, like the black and white of a woman on a couch, are only discernible from a distance, hidden in the safety zone where the smoke fumes won’t invade.

Who are these women? Why are there so many pictures that exist only as pieces of a puzzle? Lynch seems determined here to photograph nudes as an examination of sections rather than a tribute to the form. They are not necessarily erotic or sexualized as they are unsettling. The effect of these nudes will come as no surprise to those who have seen Lynch’s The Factory Photographs (Prestel, 2014). The forms and curves blend into each other, protrude from the distance, and impose on the viewer.

In the black and white photographs, darkness transforms the shapes. They move, slither away, pulsate with a smooth certainty that holds more power than we may ever be able to understand. In the press release that accompanied the book, Lynch states the obvious, which really doesn’t add to what the book really means:

“I like to photograph naked women. The infinite variety of the human body is fascinating: it is amazing and magic to see how different women are.”

Certainly this is obvious and might entice a reader into thinking these photographs are erotic, sexually charged, and enticing, but that’s not the longest-lasting effect of this work. The most frustrating part of this book might be that there is no individuality. These women are equally all one character and they are nothing, nobody, ornaments and tools. One of the more interesting color photographs here is of smoke fumes wafting from a couch. The viewer knows a woman so disturbingly hot once occupied this space. In effect, it’s the most successful photograph here in that the nudity it suggests is strong because the woman is gone.

There are obvious references here, like Francis Bacon (cited by Lynch as an influence), and the attention paid to order and composition can be seen in Edward Weston‘s attention to geometric consistency. We are all voyeurs here, all peeping Toms, unapologetic in our willingness to wait out the long moments until something happens. The long-lashes of a woman’s eyes complements her glossy lips as she stares at us through her carefully manicured fingers. Again, Lynch sees these women as varied and different, but the viewer will struggle to see things the same way.

In 2007, Lynch exhibited an interactive soundscape experience, This Air Is on Fire, at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain. It drew from experiences in childhood, adolescence, adult life — all themes similar to his films. Ten years later, David Lynch Nudes draws from what the publicity material described as being “close to abstraction [and] offering kaleidoscopic visions of the woman.” Note that the publisher this description points out the singular woman. These women are in distress, speaking on the phone, staring at us as if we have no right to be there. Nothing is as it seems.

This hardback book, 25 X 34 cm in size, is a treasure for noir fans, consistent with the themes so strong in Lynch’s films, and it is careful to cultivate more mystery than most viewers might be willing or able to understand. Lynch’s 2017 Showtime revival ofTwin Peaks is an at times incomprehensible, beautiful, horrifying majestic messy masterpiece that indulges his most onanistic tendencies while maintaining themes he has cultivated for 40 years. He directed (and co-wrote) all 18 episodes. His most recent feature before that was 2006’s Inland Empire.

Embrace the strangeness and beauty in David Lynch Nudes. His nightmare visions and obsessive adherence to a dark world of erotic fatalism where nobody who enters ever leaves is always a sight to behold.