Dead of Night is the best horror anthology film ever made. Sometimes called the “portmanteau” film, the subgenre has a long tradition beginning in Germany with the silent films Unheimliche Geschichten (Oswald,1919) and Waxworks (Leni, 1924). But Ealing Studios’ Dead of Night (Dearden, Calvacanti, Hamer, Crichton, 1945) was definitely the blueprint for all of the horror anthologies that would follow. However, most of these films fell short because the filmmakers failed to grasp the secret that made Dead of Night so effective. More on that later.

Dead of Night begins with architect Walter Craig (Melvyn Johns) driving up to a house in the countryside of Kent and being greeted by Eliot Foley (Roland Culver). Foley has asked Craig to come up for the weekend to discuss renovations to his home. But the moment Craig enters the house he is overcome with a feeling of Déjà vu. He seems to know the entire layout of the house immediately and recognizes the people who are there. It seems that he’s been dreaming about them all for a long time and can predict events before they occur. Craig is very distressed because the dreams always end in some kind of ambiguous doom for everyone.

Surprisingly, Foley’s guests find this all very exciting. In particular, Dr. Van Straaten (Frederick Valk) is skeptical about Craig’s claims and tries to psychoanalyze him instead. The other guests are much less skeptical and one by one they take turns telling Craig and Van Straaten tales of their encounters with the inexplicable.

The tales are a combination of literary adaptations as well as original stories by the Ealing Studios staff. The first tale is “The Hearse Driver”, which is based on “The Bus Conductor” by E.F. Benson. It’s a story you probably already know. “The Bus-Conductor” has been published many times and variations on it have appeared in other films and TV shows such as The Twilight Zone episode “Number 22”. I even have some vague memory of a comic book version set in an elevator.

In this adaptation, injured race car driver Hugh Grainger (Anthony Baird) tells the story of his strange encounter while convalescing at a hospital. He sees a horse-drawn hearse parked outside his window. The driver (Miles Malleson) looks directly at him and says, “room for one more inside, sir!”

Death/Nosferatu from OpenClipArt (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

Malleson is such a great choice for the role. He reminds me of Alfred Hitchcock when he would appear in costume during some of the more elaborate introductions for his 1960s TV show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The Hearse Driver is like some kind of ghoulish TV horror host, warning you of dangers from beyond, but with a wink and a smile. This one was directed by Basil Dearden.

In “The Christmas Party”, teenager Sally ( Sally Ann Howes) tells everyone about the time she went to a holiday party and played hide and seek. Running around the labyrinthine family estate, Sally ends up hiding in a distant room far from the others. This room belongs to a lonely little boy who tells her a disturbing story about his murderous sister. As Film historian Tim Lucas discusses on his audio commentary, this story was inspired by the infamous Constance Kent murder case. It’s an original by frequent Alfred Hitchcock collaborator and inventor of the term “MacGuffin”, Angus Mcphail.

I’ve always liked this one, although it’s been criticized for being underdeveloped and predictable. It does feel a bit rushed, but the predictability is part of its charm. Very few English ghost stories are surprising today. I doubt they were surprising at the time. The mysterious character you suspect might be a ghost will always turn out to be one.

The important thing is mood, and Director Alberto Cavalcanti gets the melancholic atmosphere right. The party starts playfully with costumed guests warming themselves by the fire. But as Sally gets lost in the older part of the house the mood shifts. Of all the stories in Dead of Night, “The Christmas Party” comes closest to capturing the specific sad/scary chill of a proper English ghost story.

Next up is another original by John Baines called “The Haunted Mirror”. It’s about a… haunted mirror. Peter Cortland (Ralph Michael) is given an antique mirror as a gift by his wife Joan (Googie Withers). But this mirror reflects something very unusual and Peter is slowly drawn through the looking glass.

“The Hearse Driver” (IMDB)

This subtly suspenseful segment is one of the best in the film and is especially well scored by composer Georges Auric. Director Robert Hamer effectively uses subjective point of view shots to build tension. Throughout we see the image in the mirror the way Peter sees it. But in the end, Hamer shocks us by showing that Joan finally sees it too.

H.G. Wells’ “The Story of the Inexperienced Ghost” is the source for “The Golfer’s Story”, which is an abrupt shift in tone for the anthology. This is the comical tale of a pair of golfers (Ealing comic team Radford and Wayne) competing for the same woman (Peggy Bryan). They attempt to resolve their conflict through a round of golf but following a betrayal and death, one of them begins to haunt the other from the grave.

Radford and Wayne play “Parrat and Potter”, who are just new names for their usual sports-obsessed characters, “Charters and Caldicott”. Those characters originated in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1938) and by the time Dead of Night was made, the two actors had already played the characters in several films and radio programs.

Their appeal was to the local audience, which is why this sequence was cut from the US release. Director Charles Chricton (A Fish Called Wanda) does his best with this story but the palette-cleansing shift in tone was a mistake. It was a mistake that many later horror anthologies would, unfortunately, imitate.

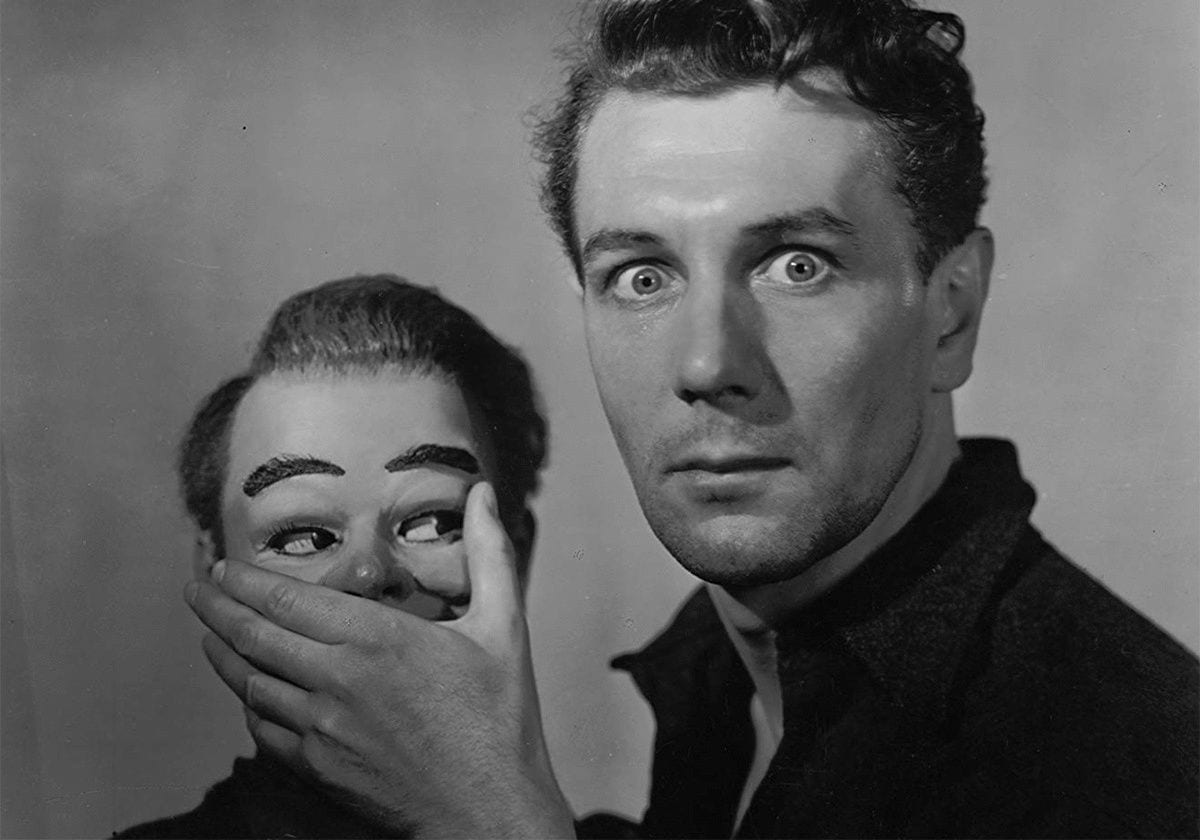

The final story, “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy”, is by screenwriter John Baines again and it’s the one everyone talks about. Directed by Alberto Cavalcanti, it’s the best segment in the anthology and probably the best film ever made on the theme of the ventriloquist and his dummy. It’s not hyperbole to say that Michael Redgrave gives one of the greatest performances in film history here.

Michael Redgrave as Maxwell Frere in “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy” (IMDB)

Redgrave plays Maxwell Frere who has, let’s say, a dysfunctional relationship with his wooden partner Hugo. It’s hard to tell which one is running the act. Frere seems to be jealous of Hugo and suspicious of his loyalty to him. Is Frere insane or is there something going on with the dummy?

Redgrave goes all out with this performance, which is so incredibly intense that the short running time is a relief. His Maxwell Frere is really hard to watch because he is so emotionally unbalanced, desperate and frightening. The final shot of the segment is chilling and a clear inspiration for the ending of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960).

“The Ventriloquist’s Dummy” is the final story, but it’s not the end of the film. What follows is the climax to the “hidden” sixth story, which is the secret to why Dead of Night works as a film. The sixth story is the film’s framing story with Walter Craig and Eliot Foley’s guests trying to convince Dr. Van Straaten that some things just cannot be explained.

Many horror anthology films attempt to hold the concoction together with a similar framing story but most fail miserably. Mostly because they use the framing story as merely a formality; A container to hold all the stories. What the makers of Dead of Night figured out back in 1945 was that the framing story had to be an interesting, suspenseful story in itself. Perhaps even the most intriguing of all the stories it carries.

Every time Dead of Night returns to the framing story the stakes get higher. Craig starts a narrative clock ticking when he remembers that in his dream someone will break their eyeglasses and this will compel him to commit a murder.

Anthony Baird as Hugh Grainger in “The Hearse Driver”(IMDB)

Director Basil Dearden evokes something truly uncanny with this framing narrative. What begins in a very cozy, familiar country house setting slowly begins to feel unfamiliar. Even the droll humor becomes quite dark. At one point, Sally has to leave and expresses disappointment that she can’t stay because she’s going to miss the part in Mr. Craig’s dream when he beats her “savagely”. She sounds like a child disappointed that she cannot stay up late to see a movie.

The exteriors seen through the back doors get darker and darker, mirroring Craig’s mood as he grows more disturbed. It’s this sequence that separates Dead of Night from all of its descendants. This framing narrative makes all of the random parts feel like they are part of a whole, not just a collection of short films held together by a title and running time.

The way “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy” descends into a maelstrom of surreality has never been matched. Dr. Van Straaten’s glasses break and Walter Craig suddenly remembers how his dream ends. Expressing the terrifying passive aspect of dreaming, he says he is unable to stop it now. He strangles Van Straaten and does get to beat Sally savagely.

You may remember that Sally had to leave earlier. Well, all logic goes out the window as Craig finds himself lost in a dream labyrinth featuring scenes and characters from all of the stories we just watched. He ends up trapped in a jail cell with Hugo the dummy.

This scene may just be the most frightening thing I’ve ever seen. Dearden simply cuts from a closeup of the inanimate dummy seated across from Craig to a wide-angle where the dummy appears to be somewhat larger. Well, that’s because Hugo is being played by a child or little person now. This person stands up, walks over to Craig and strangles him. It’s such a simple idea but the uncanny valley effect is immense.

Naunton Wayne as Larry Potter in “The Golfer’s Story” (IMDB)

The film ends with Craig waking up and driving to Foley’s house in Kent. Save for a single detail, we start the story again. The film’s circular structure has created much debate over the years and even inspired the now-debunked “Steady State” theory of the universe. It has been ripped off in numerous films and TV programs, but most filmmakers fail to understand how Dead of Night used this device. They just repeat the device of the infinite loop.

But Dead of Night is more clever. After Craig wakes up, he receives a phone call from Eliot Foley inviting him to his home for the weekend. But there is an objective cut to Foley on the other end of the call. We see him existing outside of Craig’s dream. So is this reality? We are left to wonder this as the credits roll over the same shots from the beginning of the film. Craig’s car driving down the long road….Foley greeting him outside…

Dead of Night has had a terrible history on home video in the USA. I can’t remember seeing any version before that did not look and sound awful. But thanks to Kino-Lorber we finally have a respectful 4K restoration on Blu-ray. This is the best I’ve ever seen the film. It’s not a pristine image, but I wonder if one even exists anymore. This is the original UK cut of the film including both “The Christmas Party” and “The Golfer’s Story”, which were cut for US release.

The extras include trailers for several other Kino-Lorber releases, a fantastic feature-length documentary called “Remembering Dead of Night” (75:35), and another hugely informative commentary by film historian Tim Lucas. As usual, Lucas goes into tremendous detail about everyone involved in the production as well as the context in which it was made.

Dead of Night did not emerge out of nowhere. Ealing Studios’ head Michael Balcon had been producing similar films for several years during the war and after. The Halfway House (Dearden, 1944) in particular was influential on Dead of Night and even used many of the same cast and crew. But Dead of Night’s influence went far beyond what its creators must have imagined.