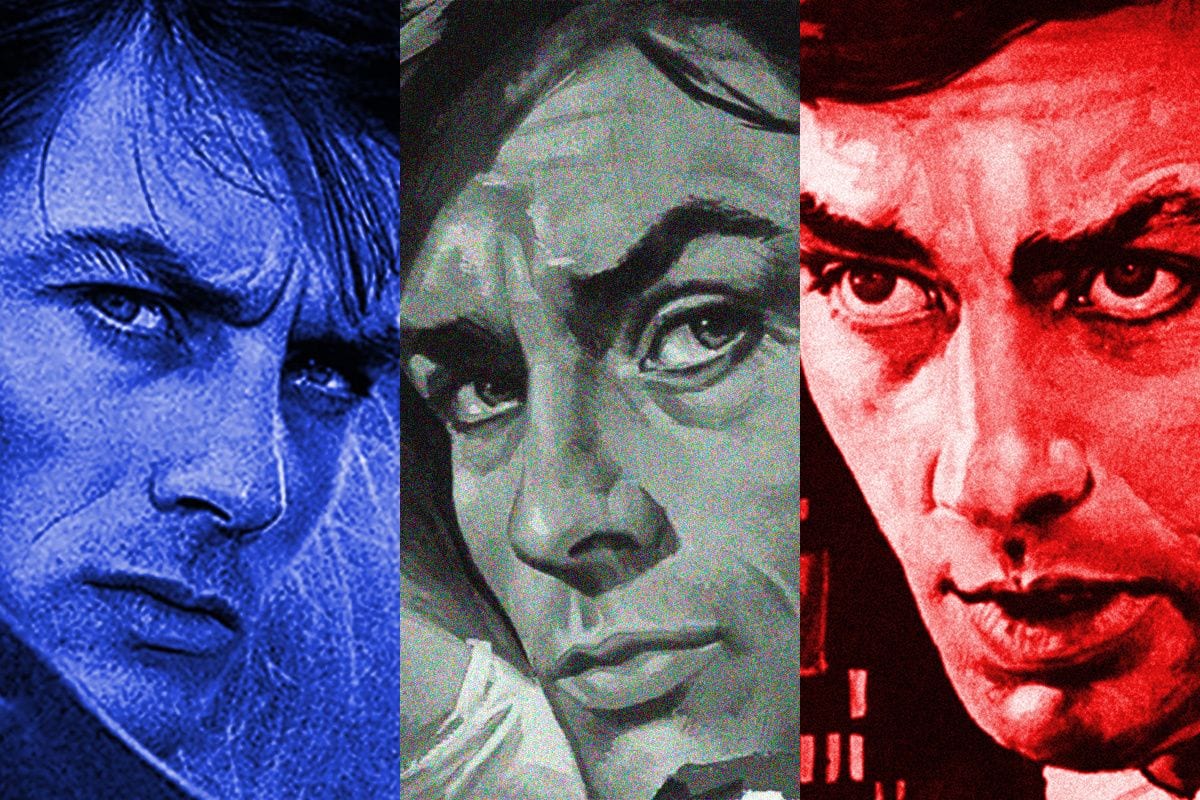

Three French thrillers starring Alain Delon, a handsome and controversial star whose on- and off-screen tough-guy personas are about equally fused, are now available on Blu-ray from Kino Lorber. In other words, unlike the examples of Humphrey Bogart or Edward G. Robinson, nobody says that this guy who plays hard bastards and gangsters is a sweetie in real life.

The more the audience is aware of this, the more his performances carry a voyeuristic weight that permits us to dislike his characters and dislike him. He crafted a hard-bitten persona used by filmmakers repeatedly until it’s impossible to separate whether fiction reinforces reality or vice versa, or both at once. Let’s take these three films in chronological order.

Diabolically Yours (1967)

Director: Julien Duvivier

We never see the car. We’re plunged into frantic forward momentum in the opening shots, scored by furious jazz rhythms. We only understand that these are subjective shots from a car because we see the road speeding toward us, but there’s no windshield or front of a vehicle in the foreground. Oddly, this breathless motion, over which the credits appear, keeps dissolving into even more disorienting subjective shots in a hospital setting. Are we experiencing this speed “now”? or are we reliving a memory or dream? And whose memory or dream or reality is it?

The opening scene of 1967’s Diabolically Yours finally establishes that our point of view belongs to Georges Campo (Alain Delon), who’s survived a car accident and had plastic surgery from apparently the most brilliant surgeon in the world. He remembers nothing, not even the fabulous woman who breezes in wearing one of her many stunningly colored dresses and identifies herself as his wife, Christiane (Senta Berger).

He eyes her appraisingly as a stranger and finds her good, so he’s happy to be taken home to his fancy mansion, where he’s attended by a mysterious pseudo-Chinese, possibly Eurasian servant (Peter Mosbacher), whom he keeps calling Mao, and by a very chummy doctor buddy (Sergio Fantoni) who keeps telling him he’ll regain his memory in time.

The narrative is defined and suffused by Campo’s frustrations — sexual in the case of his wife, who says they won’t make love until he’s regained his memory because she doesn’t want to cheat on him with a man who doesn’t remember her (!). He’s also frustrated by suspicions of being manipulated and imprisoned, and although the viewers share these frustrations and suspicions, our response adds a layer of amusement at our protagonist’s frustrations. It doesn’t bother us to watch him spinning in circles and trying to figure things out. Everything is so sleek and attractive, so cozy, that we soak in it like the doctor taking his bath or Christiane getting her massage.

Look, this is an amnesia thriller, and you can probably guess where much of this slow-burning hothouse is going. Diabolically Yours gives you all kinds of clues that fall outside of Campo’s knowledge, especially shots of the odd rapport between Christiane and her servant.

What matters is that this picture, shot gorgeously by Henri Decaë, complete with surreal dreams and possible flashbacks, casts a lovely spell of ambiguity and uncertainty as all the players cat-and-mouse each other. We need only wait and see who will polish off whom. Campo is being a good boy and taking his nightly pills, and we too gladly absorb the movie’s drug. The fact that everyone is performing or spectating is underlined in a climax that uses an impassive proscenium staging for its final gestures.

Delon and Berger make two beautiful animals, and all contributors deserve praise for constructing their glittering cage. Production designer Léon Barsacq’s outstanding career includes a famous title that this film’s title evokes: Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Diabolique (1955). He litters Diabolically Yours with mirrors, masks (even a Japanese demon mask lying unobtrusively on a low table), and textures. Georgette Fillon’s costumes for Berger and Delon are a-dazzle with color. Editor Paul Cayatte, a long-standing associate of director Julien Duvivier, provides a languid rhythm punctured with disturbing injections. François de Roubaix’s score is unobtrusive yet lively.

The script is credited to Duvivier, Roland Girard, and Jean Bolvary, from a novel by French mystery writer Louis C. Thomas. The book’s title translates as “Persecution Mania” (Manie de la persécution, 1962). IMDB adds Paul Gégauff, who worked on a lot of Claude Chabrol films, for uncredited dialogue. In their commentary, Nathaniel Thompson and Howard S. Berger express the opinion that Diabolically Yours belongs to a class of thrillers that don’t make sense when you think about them. Lord knows there are plenty such, but I politely disagree, as I’ve always thought this plot held together, even when watching the English-dubbed VHS back in the mesozoic era.

PopMatters reviewed this film in a previous DVD release, and this Blu-ray probably gives us the same StudioCanal print remastered. This time, the English subtitles are removable while the film remains in French; there’s still no option for that English dub from the old VHS.

The only extra is the commentary in which the speakers spend the whole time lamenting that Duvivier has been underrated. This was his final film in a very long and prolific career. He died as a result of a car accident, which is unfortunately ironic, before Diabolically Yours‘s release. He was 71, and this stylish sizzler doesn’t feel like an old man’s movie. A handful of his films are available in Region 1, and more deserve to be, for his output was versatile and excellent.

Farewell Friend (aka Honor Among Thieves, 1968)

Director: Jean Herman

Farewell Friend pairs the odd couple of Alain Delon with Charles Bronson, who made all kinds of interesting European pictures before breaking out as a Hollywood action star. For example, check PopMatters‘ reviews of Bronson’s work in Rider on the Rain (René Clément, 1970) and Someone Behind the Door (Nicolas Gessner, 1971). The Clément film is especially relevant because, like Farewell Friend, it was produced by Serge Silberman and boasts a similar melancholy elegance that marked many of the era’s Euro-thrillers.

Farewell Friend is a thriller and gets described as a heist film, but let’s call it what it is: an almost brazenly romantic buddy picture. As in many a screwball romance, the leads meet cute and instantly annoy each other, one pursuing the other until all resistance is broken down. Instead of stealing kisses and getting slaps, they say hello and goodbye with punches in a virtual parody of masculinity until they have to admit they’ve become important to each other. Did we mention they spend a weekend together shirtless and sweaty?

Farewell Friend‘s opening scene presents them crossing paths as demobilized soldiers arriving from stints in Algeria. Delon’s character in Diabolically Yours had also returned from Algeria, so both films carry at least a subtext of trauma and national humiliation in the structural integrity of the characters, and Farewell Friend goes farther when revealing the character’s emotional wounds over the death of a buddy who was “closer than a brother” as they “did everything together”. We won’t mention how the buddy died, but it’s highly suggestive.

Alain Delon plays medic Dino Barron, while Bronson is American grunt Franz Propp, the aggressive one who starts dogging Barron after overhearing him cold-shoulder a pretty woman. One second after telling Propp to leave him alone, Barron turns around and invites him to help spend his money, so Propp takes him to a sauna where guys in towels take his cash in a card game. This scene foreshadows the shirtless weekend.

Out of a sense of obligation to his late buddy (as we learn much later), Barron takes a job as a medic in a skyscraper of some huge company with mod flashy ads all over the walls, usually women’s faces. The damsel in mild distress (Olga Georges-Picot) prevails upon him to conduct an unlikely scheme of securing the combination of the vault next door in order to return some bonds that nobody knows are missing.

Meanwhile, Propp reveals himself as a pimp who hires a classy prostitute to put on a show for a rich bearded kinkster, his lacquered lynx-eyed wife with a long cigarette holder, and their leering entourage. While the prostitute keeps them distracted so they won’t realize they’re the ones being exploited, Propp robs them before he and the gal split the cash. If some films use heterosexual gestures as a sleight of hand to throw viewers off the scent of what’s going on, this sequence illustrates that theme by putting the woman on display in disguise as a wind-up doll. The sequence is vividly strange, arty, and unpredictable.

It’s almost a coincidence (and yet not) that, on the eve of the long Christmas holiday, Propp is drawn to the building where he knows he’ll find Barron, whom he can’t keep away from. He insists on muscling into the apparent heist for his share of the swag. This launches the long middle act in which they go from expelling their energy in rugged fisticuffs to the uneasy alliance to a long shirtless night of the soul, from which they emerge as changed men. Oh yes, there’s also lots of business involving the transfer of Barron’s gun back and forth between them.

There’s still much plot to get through, as we haven’t even mentioned major supporting characters played by Brigitte Fossey and Bernard Fresson. Quite a bit happens in this script by the elegant and original scriptwriter and novelist Sébastien Japrisot, master of the surprise twist and the disorienting narrative. A box set of the films he inspired would keep many of us awake at night.

The director, Jean Herman, is better known as novelist Jean Vautrin. In an interview, he recalls how Silberman hired Bronson after several other choices fell through, and he recalls filming as an unhappy experience full of tension between egotistical stars. The resulting film was a smash in Europe and led to Herman working with Delon again.

Herman points out Farewell Friend‘s socio-political background, with its discontented flotsam-like characters washing up from the Algerian fiasco into a greedy, impersonal, post-industrial world of glass skyscrapers and rich perverts where everyone is being exploited and looking out for number one. It’s very much a noir vision, and he identifies it as such. At this time, European writers and filmmakers – and Herman and Japrisot were both – had absorbed the Hollywood noir cycle of 20 years earlier and were re-purposing its tropes and atmospheres into contemporary veins, which is why French thrillers of the late ’60s and ’70s are “cool”, deliberate and full of weary romantic pain.

His direction is elegant and vigorous, especially in the high-class, moneyed settings where Jean-Jacques Tarbės’ cinematography pans seductively and sometimes subjectively across color-coded walls and costumes. Jacques Dugied’s chic design goes admirably overboard; Farewell Friend is dense with eye candy. Hélène Plemiannikov’s editing provides pleasure, from the disorienting opening jump-cuts to the telegraphic montage of irrelevant French leisure time (complete with an eyeblink shot of a carriage race) to the nervous transitions of the languid mid-section. As on Diabolically Yours, François de Roubaix provides the score.

This film is in English, with Alain Delon speaking in his own accent. The English credits call the film Farewell Friend without a comma, although a comma shows up on the packaging. The main theme is the ways in which men can be friends and how alcohol and the lighting of cigarettes provide moments for gazing into each other’s eyes. A French-language version was made, but unlike Kino Lorber’s Rider on the Rain, it’s not offered as an option. Were it here, we’d have what Bronson sounds like when dubbed in French by expatriate American director and blacklistee John Berry.

Commentary by Nathaniel Thompson, Howard S. Berger, and Steve Mitchell focuses on the stars, Herman’s under-viewed career, the homo-erotic arc, and whether Farewell Friend is misogynist. Some viewers might be displeased with the largely sidelined women in this high-testosterone fantasy; we’ll say only that they’re consistently smarter than the men, and things are going on with them that can’t be discussed without spoilers.

Un Flic (aka Dirty Money, 1972)

Director: Jean-Pierre Melville

Jean-Pierre Melville, one of the great independent-minded directors of French cinema, created a sleek and taciturn masterpiece with Alain Delon known as Le Samourai (1967). Their third and last pairing, Un Flic, which means “A Cop”, feels like the flipside of that film, this time with Delon’s anti-hero working on the other side of the legal fence.

Perhaps that’s why it opens with a quote from Eugène François Vidocq, the 19th Century figure who flipped from being a criminal to chief of police on the “it takes a thief to catch a thief” theory. The idea that the French cop may just as well be a criminal is reinforced by mirroring the male leads as friends who are involved with the same woman and feel no jealousy over it, perhaps because the stronger relationship is between the men anyway. If the woman symbolizes France or justice, she may just as well be with one as the other. In fact, Melville withholds narrative details so effectively that viewers spend at least half the movie wondering if the two men could possibly be partners in crime. The fact that they aren’t is almost arbitrary.

Detective Coleman (Alain Delon) introduces himself in a terse voiceover, a device that will never be used again because the film concentrates as much on his anti-hero double, Simon (Richard Crenna). We first see Simon in a lengthy set piece that opens the film, shot by Walter Wottitz as a rainy, windy, gloomy blue-tinged day in images worthy of an Impressionist painting, perhaps one crossed with Edward Hopper as we see figures cloaked in stillness and solitude, whether waiting in the getaway car or standing like statues in the bank they’re about to rob.

Melville tends to eschew dialogue when he can get away with it, and he gets away with it a lot. What dialogue exists is often inconsequential, such as Coleman’s repeated identical phrases on his car phone, the mindlessly repeated passwords of his workaday existence. Melville’s sense of narrative and momentum is so elliptical that it takes forever to hint that Coleman and Simon know each other when they meet at a nightclub full of dancing girls, and it takes even longer to establish that Simon’s wife or girlfriend, Cathy (Catherine Deneuve), is having an affair with Coleman.

When she says that she’s afraid Simon may suspect, Coleman calmly informs her that Simon knows, that he’s known from the beginning. It’s as though Cathy is another password between them. This scene finds Cathy and Coleman play-acting at cops and robbers in a way that initially confuses the viewer. As our expectations are up-ended, the camera reflects the encounter in a ceiling mirror. In a way, the scene is telling us that clichés of standard policiers don’t apply to this movie, even if it refers to them because it must.

The represssed or tightly-lidded sexuality of Melville’s heroes — one of his great films is Leon Morin, Priest (1961) — here almost breaks out in a festival of ambiguity. Coleman’s daily rounds include the body of a blonde-wigged prostitute who strangely resembles Cathy, a visit with a dignified older homosexual (Jean Desailly) who laments that his kind are traditionally victimized (and whom Coleman treats with scrupulous respect), and most oddly, a transvestite prostitute (Valérie Wilson) in another blonde wig who acts as an informant to keep the heat off.

In her commentary, which places this title in the context of Melville’s other films, Samm Deighan remarks on the surprising elements of sexuality and ambiguity that come to the surface in what turned out to be Melville’s last film. She also quotes Alain Delon’s defense of his own sexual ambiguity and rumors of his varied tastes, which sound entirely modern and play into aspects of his persona in several of his roles — see Farewell Friend above.

The major lengthy dialogue-free set piece involves a heist from a helicopter upon a train. Since Jules Dassin’s Rififi (1955), detailed dialogue-free heists had been usual in the genre, but it’s also the case that Melville always loved scenes without dialogue and various moments of “pure cinema” based on observation or the play of glances. In this case, the budget extended to hiring a copter but only using it for one shot of landing in a field, while the actual heist uses sets and model toys. The models are jarring, yet it’s a tribute to Melville’s conviction that we follow the sequence breathlessly.

The police work of connecting the dots to wrap up the plot happens off-handedly and mostly offscreen. What’s more important in Coleman’s confrontation with one of the gang (Michael Conrad, later an Emmy-winning regular on Hill Street Blues) isn’t the dialogue but the highly edited trading of stares and glances. What’s going to happen next in the police plot is so well-established that Melville dispenses with showing it.

He doesn’t need to waste our time with “what’s happening” or “what happens next” like so many pointless movies about the flurry of activity. These filmattempt to convey “action” while truly nothing is happening beyond crashes and noises. Melville belongs to a rare class of filmmakers whose “nothing happening” is a rich world. This film is about character and mood, as conveyed by imagery and largely silent ambiance, or rather musique concrète, like the opening scene of wind, bird calls, and the robbery alarm that pierces the action without causing anyone to flinch. It’s a miracle of confidence that many filmmakers have tried to emulate.

If Melville’s films can be divided into the major and minor masterpieces, and they can, this is a minor one, which means it’s more than worth seeing. It’s another film, like Farewell Friend, made in both French and English, and only the French is on the Blu-ray.

Extras include interviews with Alain Delon’s brother and the daughter of French actor Jean Gabin, who were both employed on the crew along with two children of Jacques Tati. Apparently, Melville liked to surround himself with relatives of French film history, and they recall anecdotes of the filming. A one-hour documentary draws connections between Melville’s work and modern Asian cinema, which he influenced through figures like John Woo.

- The Crossroads of Reality and Melodrama in 'Rocco and His ...

- Fate Wears a Fedora - PopMatters

- Le Cercle Rouge (1970) - PopMatters

- Past Perfect: Criterion Classics - Le Cercle Rouge (1970) - PopMatters

- 'L'eclisse' Is Beautifully Made, but Boring as Hell - PopMatters

- Sunlight As Shadow in 'Purple Noon' - PopMatters

- The Actorly Camera in Jean-Pierre Melville's 'Un flic' - PopMatters

- Honor Among Thieves, Jean Herman (film review) - PopMatters

- Dirty Money (Un Flic) - PopMatters