Diana Ross began 1979 in Oz, or at least the New York version of it. Over the past two years, the city had catapulted the singer to new heights, from winning a Tony Award for An Evening with Diana Ross (1976) at the Palace Theatre to starring in Sidney Lumet’s Gotham-based film adaptation of The Wiz (1978). The singer’s next album, The Boss (1979), would pulse with the sophisticated and eminently stylish sounds of Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson, New York’s quintessential songwriting/production team. In becoming The Boss, Ross left Oz and entered a lush musical Eden.

The Boss bookended a decade of change for the singer. Only six years after Ross ventured solo from the Supremes in 1970, Billboard named her “Female Entertainer of the Century” (1976). She’d already scored several number one hits, hosted her own television special, Diana! (1971), earned an Academy Award nomination for her riveting portrayal of Billie Holiday in Lady Sings the Blues (1972), and recorded the Oscar-nominated “Theme from Mahogany (Do You Know Where You’re Going to)” (1975) for her second motion picture. Beyond the Broadway stage, NBC’s broadcast of An Evening with Diana Ross garnered four Emmy nominations while Motown’s accompanying LP offered a bracing overview of the singer’s career.

On stage and on record, Diana Ross was in peak form by the late 1970s, unveiling a dazzling vocal maturity on Baby It’s Me (1977) and mastering first-rate material like “Home” and “Be a Lion” in The Wiz. “Miss Ross is one of the most distinctive and versatile popular singers of our time,” The New York Times declared in a review of the singer’s November 1979 appearance at Radio City Music Hall. Perhaps more than any other Ross album, The Boss channeled the power and dynamism of the singer’s live performances into an eight-song tour de force.

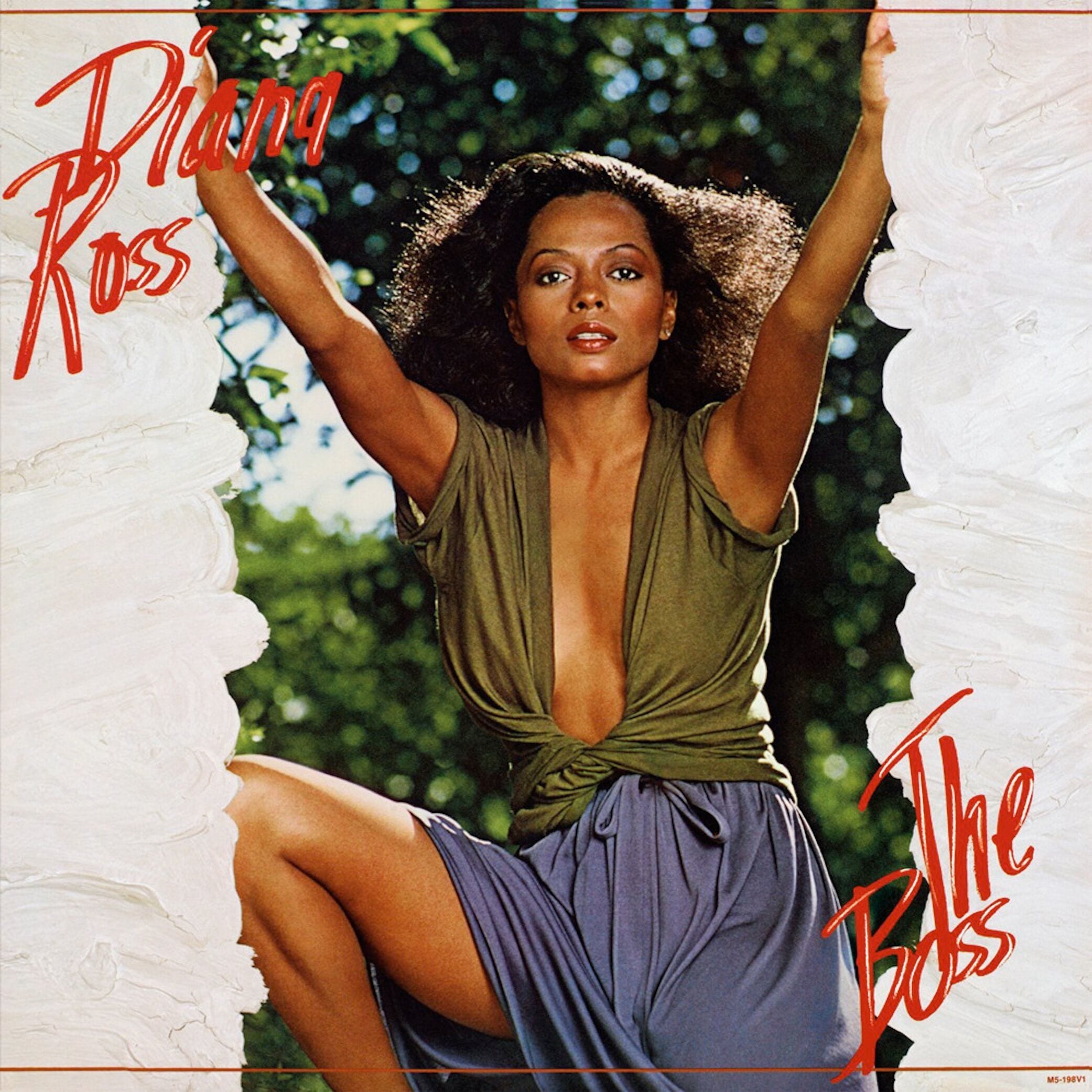

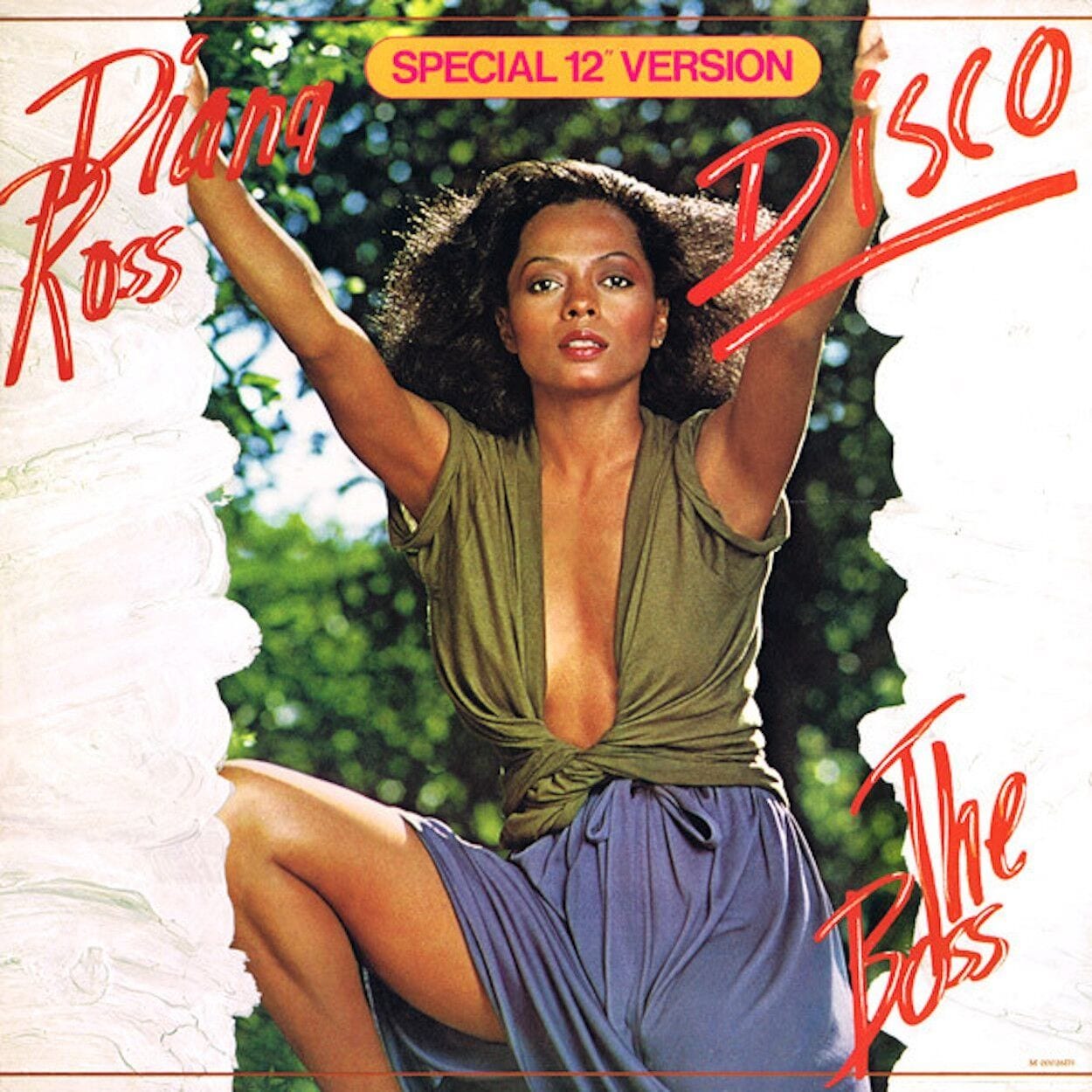

The Boss is really an album of declarations. Half the song titles double as boldface personal statements, whether “It’s My House” or “I Ain’t Been Licked”. Ross contours the words and melodies with confidence, from her opening cry on “No One Gets the Prize” to the way she asserts “I’m here and I won’t apologize” on “I’m in the World”. Even the cover photo depicts Ross as a living, breathing exclamation point. A woman basking in her strength and sexuality, beckoning the listener to move their body on the dance floor (or in the bedroom).

“Vocally, we wanted Diana to show off a little more and take more risks,” says Valerie Simpson about producing Ross’ very first gold-certified album. “We put her in keys that would stretch her, so she’s at the top of her range. She really stepped into her own to sing full-out, full voice. She never failed us.” In this PopMatters exclusive, Simpson shares how Ross soared on The Boss while three of the album’s arrangers, Paul Riser, Ray Chew, and Rob Mounsey, plus bassist Francisco Centeno, recall Ashford & Simpson’s brilliance behind the beat.

Supremes to Solo Stardom

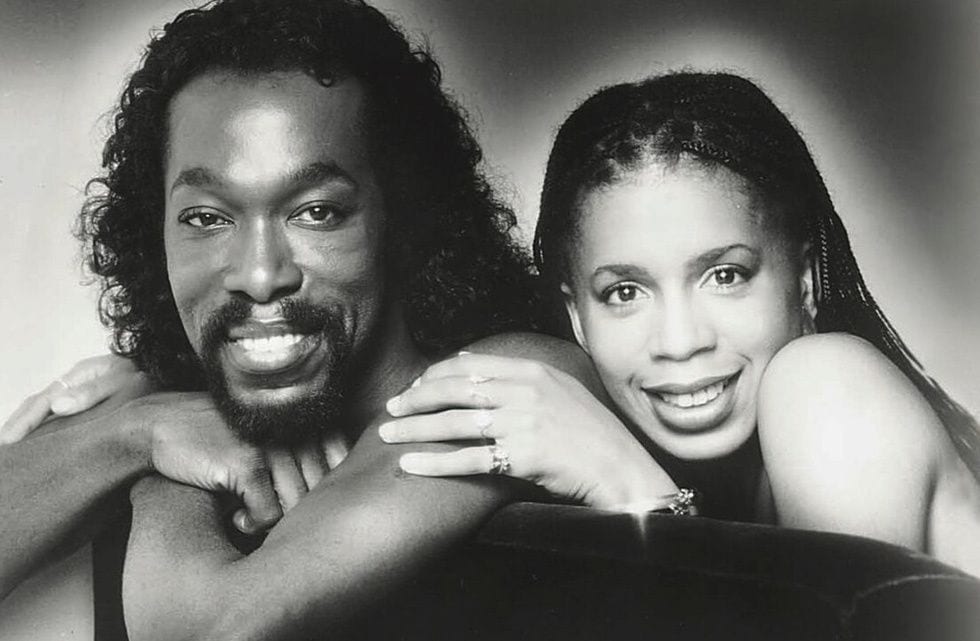

Diana Ross with Ashford & Simpson — it was an inspired pairing that first crystallized a full decade before The Boss. Following their prolific writing partnership with Joshie “Jo” Armstead on hits like “Let’s Go Get Stoned” and “I Don’t Need No Doctor”, Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson brought their singularly soulful aesthetic to Motown in 1966. “The way Nick and Valerie voiced their chords for their songs was different,” says legendary Motown arranger Paul Riser, whose intricate orchestrations embellished the duo’s musical language. “Their writing style was different from Stevie Wonder’s. It was different from everybody’s style at Motown.

“When Nick and Valerie arrived, someone in the A&R department at Motown assigned them to me. They thought that it was that unique of a combination. The three of us were like a trinity. They felt confident with me. It made a difference. They always gave me great demos, always. The best demos.”

After writing several hits for Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, including “Your Precious Love” and “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing”, Ashford & Simpson helmed “Some Things You Never Get Used To” and “Keep an Eye” on Diana Ross & the Supremes’ Love Child (1968), an album that signaled a stylistic departure from the trio’s work with Brian Holland, Lamont Dozier, and Eddie Holland. “The songs had changed from ‘Baby Love’ and ‘Where Did Our Love Go’,” says Simpson. “Nick called her voice — in those songs — a voice that conformed to infancy. It was child-like. It was the right sound on those songs. That’s what made them hits. Holland-Dozier-Holland really captured that. I understood what they were doing getting the hits in the early days.”

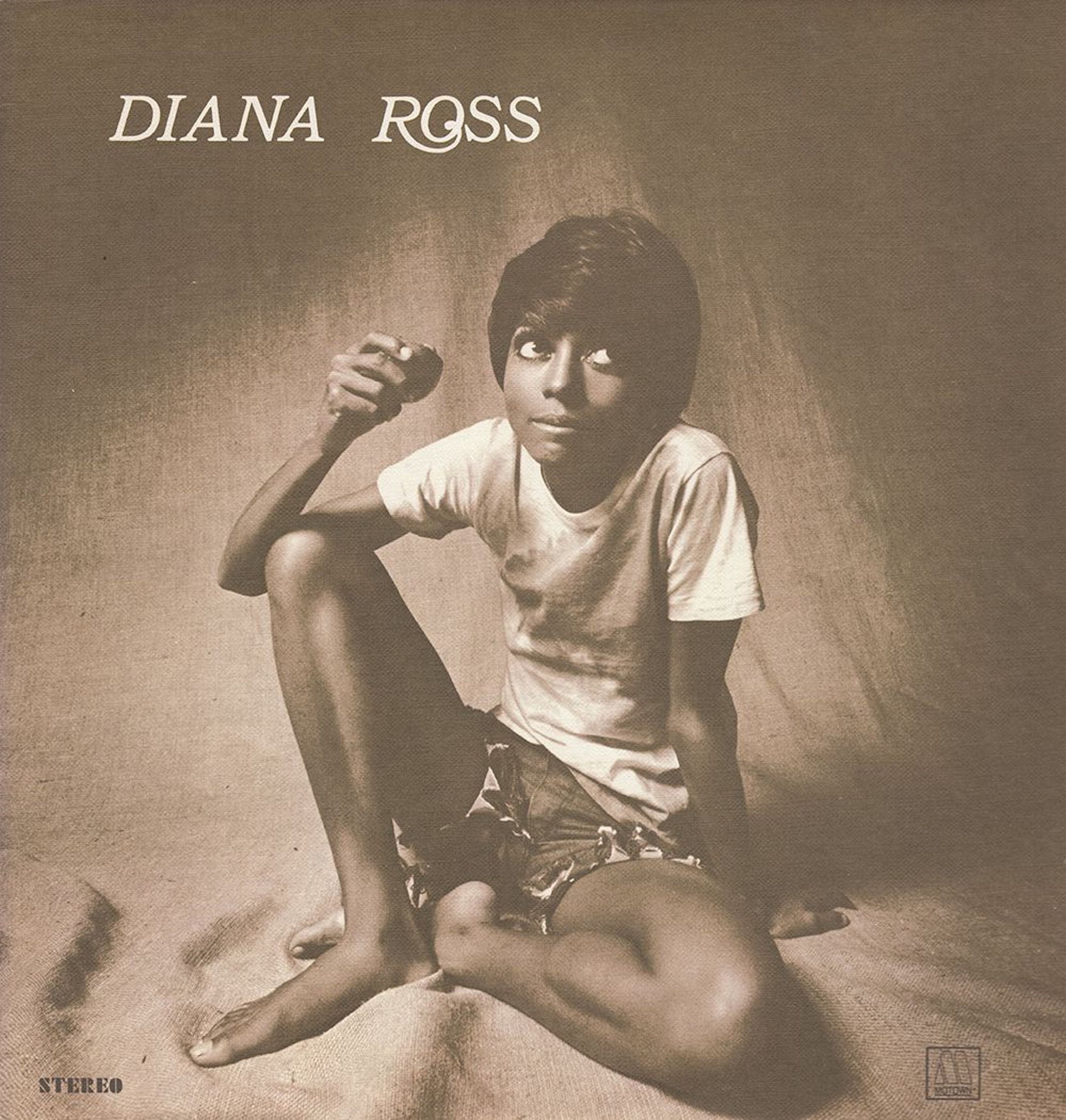

Just two years later, Ross bid farewell to the Supremes on 14 January 1970 at the Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas. With 12 number one singles to the trio’s credit, what kind of statement would Ross make after fronting the most successful female group of all time? Johnny Bristol, who’d produced “Someday We’ll Be Together” (Ross’ final chart-topper with the Supremes), had already cut “These Things Will Keep Me Loving You” with the singer. Fifth Dimension producer Bones Howe even recorded a few sides with Ross, including Laura Nyro’s “Time and Love” and “Stoney End”. Ultimately, Ashford & Simpson were selected to fashion the singer’s highly anticipated solo debut.

Ashford & Simpson’s writing, producing, singing, and playing on Diana Ross (1970) constituted a creative leap for the duo. “When we got to Diana, I think she was interested in a more mature thing,” says Simpson. “She was stepping out from a group. Your voice goes through things. You personally go through things. I think all of that really decided the kinds of songs we wanted to write for her. We got a chance to see a different Diana.”

Opening track “Reach Out and Touch (Somebody’s Hand)” was an instant pop anthem, a song that accentuated the singer’s innate ability to connect with listeners. Though Simpson would also record “Now That There’s You” and “Can’t It Wait Until Tomorrow” on her solo album Exposed (1971), Ross shaded both songs with her inimitable delivery, furnishing the album with two of its strongest cuts. She also revisited “Keep an Eye”, turned Gaye and Terrell’s “You’re All I Need to Get By” into an appealing solo number, and dusted off “Something On My Mind”, an older tune that Ashford & Simpson had produced for Syreeta.

The last track on Side One towered above everything else on the album, “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”. Ashford & Simpson brilliantly reimagined their own song, a perfect marriage of soul and pop that Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell first immortalized in 1967 and Ross had sung with Dennis Edwards on Diana Ross & the Supremes Join the Temptations (1968). The duo revamped the tune as an epic, six-minute solo masterpiece for Ross, replete with a heavenly choir, spoken-word interludes, and Paul Riser’s majestic orchestration.

“That particular version of ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’ had a classical feel to it,” says Riser. “Motown had never done anything of that nature. Never. It was like an experiment of sorts to see what we would come up with. It had symphonic qualities to it. You could hear the different movements. It was refreshing to me.”Released in July 1970, an edited version of “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” far surpassed the Top 20 success of “Reach Out and Touch”, Ross’ debut single. It crowned the Hot 100 for three weeks, coupled with a one-week stint atop the R&B singles chart in October 1970, and would earn the singer a Grammy nomination for “Best Contemporary Vocal Performance, Female”. In the meantime, Ross released her second album, Everything Is Everything (1970), produced by Deke Richards and Hal Davis. With “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” boldly ushering Motown into the 1970s, however, Ashford & Simpson were enlisted to produce another set for Ross, Surrender (1971).

At a time when Motown label mates Marvin Gaye explored What’s Going On (1971) and Stevie Wonder proclaimed Where I’m Coming From (1971), Diana Ross recorded an album of such command that it set a new benchmark in her career. Few moments on her debut prepared listeners for the driving thrust of “Surrender”. It set the tone for an album where, track for track, Ashford & Simpson showcased the singer’s vocals to mesmerizing effect. “Diana always nailed it and gave you more than you had asked for,” says Simpson. “She’s a hard worker. She always was.”

Surrender also underscored Ashford & Simpson’s peerless musicality in crafting mini playlets like “Did You Read the Morning Paper” and “I Can’t Give Back the Love I Feel For You” (previously recorded by Syreeta and Kiki Dee). Simpson herself anchored the album with her distinctive piano style. “Valerie’s just a great keyboardist,” says Riser, who developed many of his arrangement ideas from Simpson’s playing. “I’d always focus on the piano. It’s churchy. It’s got a classical approach to it. There’s nothing ambiguous about Valerie’s playing — her movements and her transitions from one chord to another chord, or the transition from one section to another section.”

Ashford & Simpson’s second outing with Ross gave Motown a wealth of potential singles. “Remember Me” emerged as the album’s biggest hit, reaching the Top 20 five months before the album’s July ’71 release, while “Surrender” and a slow-burn reworking of Holland-Dozier-Holland’s “Reach Out, I”ll Be There” both made the Top 40. Elsewhere on the album, Ashford & Simpson deftly recast songs they’d produced for other Motown acts, including “I’m a Winner” (Martha Reeves & the Vandellas) and “Didn’t You Know (You’d Have to Cry Sometime)” (Gladys Knight & the Pips).

Two years passed before Ashford & Simpson re-teamed with Ross on “Just Say, Just Say”, their sole contribution to the singer’s duet album with Marvin Gaye, Diana & Marvin (1973). In between, Simpson released her second solo set Valerie Simpson (1972) on Motown’s Tamla imprint, scoring a Top 40 R&B hit with “Silly Wasn’t I”. When Ellis Haizlip featured Ashford & Simpson on his New York-based television show Soul! in October 1972, the duo’s onstage chemistry was undeniable. Within a year, Warner Bros. signed Ashford & Simpson as a recording act in their own right.

The Warner Bros. Years

Beginning with their Warner debut, Gimme Something Real (1973), Ashford & Simpson’s albums distinguished the duo from their contemporaries. “Their stuff was always very passionate and dramatic, almost theatrical,” says bassist Francisco Centeno, a mainstay of the duo’s band since Simpson’s second solo album. “It wasn’t just that they were churning out songs. Every song was like an experience. Nick’s lyrics were always so grand. You can almost hear a baroque influence in the way Valerie moves with the chords. They’re sophisticated for pop songs. It’s not just simple I-IV-V stuff. There’s a classical training there.”

Paul Riser resumed his role as the duo’s arranger, shrouding their first Top 40 R&B hit “(I’d Know You) Anywhere” with shimmering elegance. “There’s a goodness there that didn’t go away just because we left Motown,” says Simpson. “Paul was a natural go-to. It’s a relationship — somebody that you know you can depend on, because there are times when you give a song to somebody and they don’t take it anywhere so you’re still stuck where you are. Paul was always dependable.”

In a sense, Riser set a standard of excellence for the arrangers who followed after Ashford & Simpson’s second Warner album I Wanna Be Selfish (1974). Leon Pendarvis, William Eaton, and Al Gorgoni were among the masters who arranged Come As You Are (1976), So So Satisfied (1977), and a pair of albums the duo produced for Motown group, the Dynamic Superiors. Despite the albums’ limited commercial appeal, each LP contained thoroughly exquisite work, including “Somebody Told a Lie” and “Believe in Me”, as well as club staples like “One More Try”, “Over and Over”, and the Top 40 dance hit “Tried, Tested and Found True”.

Send It (1977) amplified all the strengths of Ashford & Simpson’s style and rewarded the duo with their first Top Ten R&B album. Featuring Riser’s string and horn arrangements, “Let Love Use Me”, “Send It”, and the sweeping instrumental “Bourgié Bourgié” seemed beamed from the heavens while Francisco Centeno ignited “Don’t Cost You Nothing” with an irresistible groove. Send It also introduced a new addition to Ashford & Simpson’s band, Ray Chew. In fact, Chew and Centeno had both attended High School of Music and Art together. He replaced former classmate Nat Adderley, Jr. as the duo’s Musical Director and became an integral part of arranging rhythm tracks for their songs, in addition to laying down keyboard parts on clavinet and Fender Rhodes.

“We worked together more in the fundamental beginnings of the tracks,” Simpson notes about Chew. “It’s like a third arm, somebody who knows you and knows what you need. I like everybody to have a say and Ray was open to that. Now, people don’t even record together. You miss so much when you don’t allow the energy to flow. He was really good with that. It made it easy. The musicians trusted him, and they knew us, so everybody got a chance to shine. There was no ego involved.”

Chew explains the process of how Ashford & Simpson’s songs would typically develop from demos to fully orchestrated tracks. “I would get a cassette of Nick and Val singing with a piano,” he says. “I would hear some specific stuff that Val’s playing, so I’m interpreting in my mind what I think is right. I would write out all of the rhythm parts.

“We would cut the rhythm all during the week. While we were cutting the rhythm, Nick would sing the song so we’d know how to interact with the vocals. Eric Gale (guitar) and Francisco Centeno (bass) were always there, and then there’d be different drummers. I’d play Rhodes or I would conduct the rhythm section. Valerie would play piano and everybody knew that we could bounce off of that. Nick and Val were savvy enough producers to know how to activate the wonderful genius in all of these great players. We’re not going to stifle somebody and say what you can and cannot play, however, there’d be some things where we’d say ‘We need this over here in this spot’, so I’d write it in.

“After everybody left, Eric would stay and get a lot of his guitar stuff done. Once we got the rhythm done, Nick and Val would give a copy of that recording session to the ‘sweeteners’ — John Davis, Paul Riser, Rob Mounsey, Leon Pendarvis — who would write strings and horns on that. That’s how we did a lot of those records after Send It.”

1978 marked a particularly fertile time for Ashford & Simpson. They wrote “I’m Every Woman” for Chaka Khan’s solo debut, contributed “Ride-O-Rocket” to Blam!! (1978) by the Brothers Johnson, and co-wrote Quincy Jones’ chart-topping “Stuff Like That”. Their own album Is It Still Good to Ya (1978) crowned the R&B albums chart and landed in the Top 20 on the Billboard 200, standing as their biggest album of the decade. The scintillating, club-driven “It Seems to Hang On” soared to number two on the R&B singles chart, with “Is It Still Good to Ya” following at number twelve. Even album tracks like “Ain’t It a Shame” found Ashford & Simpson at the top of their game.

Diana Ross was about to benefit from the duo’s winning streak. Since last working with Ashford & Simpson in the early-’70s, Ross had produced her own version of their song “Ain’t Nothin’ But a Maybe” on Diana Ross (1976), brought the duo’s “What You Gave Me” into the disco era on her most recent album Ross (1978), and recorded a pair of tunes they’d written with Quincy Jones for The Wiz. Ashford & Simpson had conceived “Can I Go On?” and “Is This What Feeling Gets” for Ross’ sensitive portrayal of Dorothy. In writing and producing songs for The Boss, they’d derive inspiration from the best source of all: the singer’s own life.

“All the Diana’s She Wanted to Be”

In a January 1979 cover story for People Magazine, Diana Ross discussed her recent move to the east coast, nearly 3,000 miles away from the careful protection of Motown and label founder Berry Gordy. “I’ve wanted this freedom of space for so long,” Ross told the magazine. “I feel like Dorothy. Suddenly, BOOM, I’m in a whole new world.” The singer’s initial discussions with Ashford & Simpson about her next album echoed those same sentiments.

“When we did The Boss, Diana was stepping away from Berry,” says Simpson. “She said, ‘I really want to be more in charge of this. I want songs that reflect what I’m going through.’ It made it very easy to do a song like ‘The Boss’ because that’s what she had become in her own life. She’s her own person now.”

The New York branch of Sigma Sound served as home base for the sessions. Ashford & Simpson had begun using the studio just a couple of years earlier on Send It. “It was a really good studio,” Simpson continues. “Fortunately, we had a big enough budget so we could pay those heavy duty prices. A lot of people would book a studio and lock it down for days, but we didn’t do that. We didn’t have an endless budget. We had to come in prepared and come in knowing what we wanted, and get it. I think we got that from our early days at Motown. We had good training about not wasting time.”

Ashford & Simpson immediately commanded listeners’ attention on The Boss. The background vocalists announce “No One Gets the Prize” with a hushed sense of anticipation before Ross sounds a full-bodied wail. Never before had she made such a grand entrance on an album. “Isn’t that a great opening?” exclaims Simpson. “We just wanted it to be dramatic. We were always about drama. [laughs] We love drama.” The introduction merely hinted at how high the sparks would fly once the beat kicked in.

Renowned bassist Anthony Jackson propelled the story with a popping bass line. Ray Chew recalls, “Whatever happened that day, Francisco couldn’t make it, so they called Anthony. That was his style that helped give ‘No One Gets the Prize’ a particular pulse. He brought his flavor to that song. He gave it that little bounce.”

Arranger Rob Mounsey, who’d only recently begun working with Ashford & Simpson at the time, masterfully pit strings and horns against each other, simulating the song’s tale of dueling girlfriends. “They kind of trade focus with each other,” he says. “The strings make sort of a sweeter section. Sometimes the French horns are like an orchestral thing and then, at other times, the trumpets, trombones, and saxophones play that funk-staccato style that comes from Jerry Hey out in LA. There’s also a thing I like to do that’s a little bit stolen from Stevie Wonder, the way he could have little horn sections that were about trumpet and alto sax, but the trumpets are playing low on the instrument. It’s almost a pumping, snarling kind of feeling.”

Ross and the musicians were fully committed to telling the story. “We sang the background with intention, the rhythm track is with intention, so when Diana hits the track, she’s got to have the intention,” says Simpson. “You can’t lay back and coast. There’s no coasting allowed.” Not missing a beat, Ross effortlessly recounts a litany of transgressions between two friends-turned-rivals.

The song’s breakdown featured some memorable exchanges between Ross and Eric Gale. “Back off!” the singer warns as Gale punctuates the drama with some well-deployed “pow’s” on his guitar. “That was an effect,” notes Chew, whose work on the rhythm arrangement drove the action forward. “‘Back off’ was scripted,” adds Simpson. “Most of that was scripted. Diana probably added in a thing or two.”

To this day, “No One Gets the Prize” stands among Simpson’s favorites on the album. “I love that song,” she says. “Musically, it builds. It’s exciting. When you’re doing something that’s exciting, you can go full gusto. I like that everybody feels that. They feel that momentum and respond. It never was a big hit, but the clubs liked it.”

In a way, “I Ain’t Been Licked” continues the story of “No One Gets the Prize” with Ross emerging as the unscathed survivor. The opening fanfare conveys victory as Ross struts with the bearing of a champion ready for another round in the ring. “Got my second wind,” she sings, bringing a bit of spunk to the lyrics.

“Licked” also raised an eyebrow or two in the studio. Chew recalls the band’s initial reaction to the song title. “We’re sitting there at the rhythm session and everybody made a quick little joke about that — ‘Oh, I ain’t been licked!” he laughs. “We always liked little double entendres,” adds Simpson. Think what you want to think … It don’t scare me none! [laughs] It gave ‘the children’ something to talk about. I think the lyric speaks for itself. All those other things going on? Hey, if it works for you, it works for me!”

Ashford & Simpson gave Rob Mounsey ample space to animate the song’s triumphant spirit. “Rob is particularly good in coming up with horn lines that I hadn’t heard before,” says Simpson. “Some of it was just reinforcing what Valerie played on piano or what the band played,” Mounsey adds about his arrangement. “You try to keep a variety circling around, but without ever getting in the way of the song or getting in the way of the lyrics. You support the curve and the arc of the song — the highs and lows.”

Just like they’d done on “No One Gets the Prize”, Raymond Simpson and Ullanda McCullough blended seamlessly with Ashford & Simpson on the tune’s background vocals. “We always knew what we wanted in the background,” says Simpson. “It has to be somebody who really recognizes harmonies and understands that we like overlaying and overlapping parts. Ullanda had a nice clear soprano voice. Ray’s a really good singer. Once you teach them the song, the background part is already laid out, so they know exactly what’s expected.” Adding extra punch to the chorus, all four vocalists helped power Ross’ proclamation to the stratosphere.

“All for One” brought a moment of tranquility to the album. It proceeds like a conversation between Ross and the listener, not unlike her vocals on “Reach Out and Touch” years earlier. “It’s a quiet song but one that I like a lot,” says Simpson. “It’s a coming-together. You want to give people songs that will mean something to them as they go along. We were speaking truth to her musical journey. Years later, ‘All for One’ can still resonate with her and with audiences. Diana could pull that out and use it.”

Once again, Rob Mounsey crafted a stellar arrangement for Ashford & Simpson. “Creating these orchestra arrangements for their songs is a special kind of musical challenge,” he explains. “It’s not a challenge in the sense that it’s difficult, but it’s a challenge to do exactly the right thing and not too much of it. Know when to really get out of the way and know when to contribute something. Know when to step to the front of the stage and when to back up.”

Ross takes center stage on “All for One”, caressing the notes with tenderness and a nuanced interpretation of the lyrics. “I love the bridge on that song,” says Simpson — “‘We’re all down here under the sky.'” Ross’ voice shines like a radiant light as she implores “Won’t you try, won’t you try”. It’s a customarily strong performance.

The album’s original Side One closed with a career-defining anthem for Diana Ross. “The Boss” seemingly made Douglas Kirkland’s cover photo come to life. It captured Ross, vital and energetic, frolicking freely amid Ashford & Simpson’s impeccable production. “Now, surprisingly, ‘The Boss’ was a ballad,” Simpson shares. “We wrote it as a ballad, but we realized that the ballad didn’t do it justice. It didn’t have any fire. I decided to invigorate the song by giving it a tempo. It became bossier! [laughs] The beat just made it a more interesting and more fun song.”

Ashford & Simpson invited Philadelphia-based producer John Davis to outfit “The Boss” with strings and horns. “I always like trying people and seeing what they bring to whatever it is you have in your mind,” says Simpson. “In some kind of way, we got hooked up with John.” As the leader of John Davis & the Monster Orchestra, he’d become one of the most creative figures in disco, climbing the charts with tracks like “Ain’t That Enough for You”. In fact, Ashford & Simpson would later contribute vocals to Davis’ own version of “Bourgié Bourgié” on The Monster Strikes Again (1979).

“The Boss” galvanized the band’s playing. “I played ‘The Boss’ real solid,” says Francisco Centeno. “If you listen to the verse, there’s a lot more space in the bass. I’m not plowing eighth notes through it. I broke it up a little bit. What you end up getting is something that’s a little more elegant. That was a conscious effort. I remember saying, ‘I’m not going to make this my basic disco record like the last three I did this morning.’ I’m playing with a little more slide instead of just pumping it through. It’s a little sexier.”

Drummer John Susswell helped give the song its rhythmic foundation. “We all loved John’s playing,” says Ray Chew. “He had a rock-solid feel. Then he would add some really nice wonderful creative stuff. His playing allowed Francisco and guys like Anthony Jackson to do their thing. You can’t bounce around as a bass player unless you have a solid beat. The interaction between bass and drums is fundamental. Certainly, that allows the rest of us to play on top of that and do our thing.”

The centerpiece of “The Boss”, however, was Ross herself. Her visceral connection to the song generated some of the most exhilarating vocals of her career. “When it gets to that breakdown and she starts whooping, many people thought that was me and it wasn’t,” Simpson recalls. “We caught Diana in a glorious free moment. It was totally spontaneous. It was nothing I could have told her to do. I didn’t feel that. She felt that.” From the breakdown to the closing vamp, Ross delivered a peerless performance.

Side Two took a more sensuous turn, both musically and lyrically. “Once in the Morning” kicked off the proceedings with another nod to the clubs. This time, Paul Riser was summoned to write a string arrangement for the tune. It offered a whole other context for his creativity. “Disco allowed me to be more aggressive in string writing, give it more rhythmic feels and whatnot,” he says. “That’s why I enjoyed it.”

“Once in the Morning” worked just as well for the boudoir. “It’s a question of giving a person more colors,” says Simpson. “Diana’s always been a sexy lady so to actually speak on it, as long as it doesn’t go raunch, you can go there. Nick was very good at that — making things sexy but not dirty. Diana never had to say, ‘Oh no, I can’t say that.’ He would always clean it up in just enough of a way that it was palatable. You don’t want to sound like you ain’t doin it!” [laughs]

Three years earlier, the chart-topping “Love Hangover” had melded a more sensual side of Ross with a disco beat. Whereas her ad libs on “Love Hangover” had a relaxed, languid quality, her vocals on “Once in the Morning” were steeped in unbridled ecstasy. “Her riffs are wonderful,” says Simpson. As the song reaches a climax, so does Ross. Her desire is so intense that she turns the word “morning” into a passionate, ten-syllable explosion.

Featuring a lilting string and horn arrangement by John Davis, “It’s My House” spotlights a more coyly seductive performance from the singer. “If you come on in, you’re gonna get much more,” she teases, welcoming a suitor so long as he follows her rules. Ross might be in charge but whoever joins her is gonna have a good time.

“It’s like a double meaning,” Simpson notes about the song. “It’s an empowered thought, but you don’t want to seem overbearing with it. Adding the playfulness to it is probably how we were pulling it back just a little from her being too bossy! [laughs] Maybe at a different time we would have made it a more forceful thing. At the time, we were trying to strike a balance of light-hearted but [pauses] ‘it’s my house’.”

Ross’ fetching vocal on “It’s My House” stemmed from Ashford & Simpson’s specific approach to working with the singer. “I would do a demo and we’d keep it pretty simple,” says Simpson. “No ad libs or anything. You never want to instruct. You want her to learn the song, you want her to know the melody, and then make it her own. I was very careful about that.” Even when uttering a simple phrase like “anytime” during the fade, Ross imbued “It’s My House” with a unique flair.

In truth, by the time Ross cut her vocals on The Boss, the strings, horns, and rhythm parts had already been recorded, making her sense of spontaneity all the more remarkable. “It was an amazing process that Nick and Val had,” says Rob Mounsey. “It was like the house is decorated and Diana could just walk in and do her thing. A beautiful table was all set for her. ‘We made it especially for you. Walk in, be yourself, and go home.’ I don’t know who else has done it that way, but that was their way of doing it. People like Diana would just trust them to do it, mostly on the strength of the songs, above everything else.”

The world that Ashford & Simpson created on “Sparkle” offers untold pleasures. Within the first few seconds of the song, Ross lures listeners into a lush paradise where flutes, percussion, and Simpson’s translucent touch on piano weave in between Centeno and Susswell’s understated, almost gentle phrasing. It’s arguably the most alluring sequence on the album, even if the song traces a bittersweet storyline.

“There are quite a few songs that I’ve done with Nick and Val that go into a bossa nova kind of feel,” says Centeno. “I think ‘Sparkle’ has that thing. If you listen to ‘Send It’, it’s similar. I was in love with Brazilian music. I was bringing a lot of that into their records too. I used a combination of bossa nova bass lines, those long notes like on ‘The Girl from Ipanema’, and baião, which is a little more funky, rhythmic, and Latin-sounding.”

Paul Riser’s sumptuous orchestration only amplified the more exotic elements of the song. “Paul was particularly good with flutes and all of that lighter, lovely stuff,” notes Simpson. Riser himself knew how to refine all the ingredients. “I’ll tell arrangers, always stay within the context of that song,” he says. “Never get away from what the intent of the song is. If it’s a decent piece of product in the demo stage, don’t take it so far left or right. Keep it in that center zone and you can’t go wrong, simply put.

“Being a classically trained person, I’m constantly cognizant of the balance between strings and horns, the intertwining, the when-to and when-not-to in respect to the voice and the rhythm track. Each group of instruments has its place. Because of my training, it’s easier to provide those things. I stress that all the time with arrangers — learn theory and never quit listening to classical music.”

Ashford & Simpson brought Michael Brecker aboard to record a sax solo on “Sparkle”, stirring even more textures into the mix. “You try to give people things that you think they can get into and come out with something fresh,” notes Simpson, who’d worked with both Michael Brecker and Randy Brecker on countless jingles. “It’s a pleasure when you get a chance to sink your teeth into something. We may have done two takes of the solo, but you could have picked the first one if you wanted.” Ever the pro, Brecker complemented the spectral tone of Ross’ voice during the break, making “Sparkle” shine even brighter.

Ray Chew also witnessed Brecker’s genius at close range on several occasions. “Michael was just an excellent player,” he says. “Michael Brecker and Eric Gale were some of the go-to guys when you wanted a solo. I don’t think you can break down greatness other than it just stands above the crowd. Greatness knows how to be great in and of itself.”

Greatness could be found in every note of the album’s closing statement, “I’m in the World”. It’s both a powerful summation of the seven preceding songs and a glimpse of where Ross found herself at that moment in her life. “I’ll take my chances,” she sings and it’s easy to draw parallels between the lyrics and the actual risks she took in relocating to New York, not only as one of Motown’s biggest stars, but as a newly single mother raising three daughters.

Musically, “I’m in the World” stood apart from the rest of the album. “Nick and Valerie knew exactly how to write for Diana,” says Paul Riser, whose stunning orchestration on the song brought Ross full circle from the palatial arrangements of her solo debut. “It’s like a spotlight number where she’s got the dress on and the drink’s on the piano,” Simpson chuckles. “As she proved with Lady Day, Diana could do anything, so all you had to do was give her a chance to explore that avenue, that kind of a song. There’s a place where that kind of a song will work, but you need to have it in your repertoire and say, ‘This is mine. I put my stamp on it.’ She knew how to do that. She was colorful and she deserved to be all the Diana’s she wanted to be!”

‘The Boss’ Has Arrived

Beneath the midday LA sunshine, Diana Ross fixes her gaze towards a camera. She has one leg turned out as if she’s ready to sprint through the fame. Raising her arms, she touches the promise of victory. How could one photograph so definitively convey the essence of The Boss? That’s exactly what acclaimed photographer Douglas Kirkland achieved during a session with Ross at his home in the Hollywood Hills.

Shooting outside sparked a sprightly kind of energy in the singer. “I suggested it,” says Kirkland, who’d struck a rapport with Ross during her photo session for People Magazine‘s cover story. “It felt right for this particular mood. Diana had an acute sense of what she wanted to project. I wanted to capture her as herself.”

Attired in casual wear, Ross seemed to glow before Kirkland’s camera. “A photo session is like a dance between the photographer and the subject,” he continues. “I coax and direct but let my subject move while I encourage them. I always have music playing during photo sessions. In this case, Diana’s music. We let it flow and came up with this image.” The cover photo perfectly embodied the natural vitality of Ross’ work with Ashford & Simpson. 40 years later, Kirkland himself holds the shot in high esteem. “It is still one of my favorite photos of Diana,” he says.

Kirkland’s cover portrait defined the summer of 1979 as The Boss heralded Ross’ return to the charts. “It was a really exciting time,” says Rob Mounsey. “You saw the record in record shops. You heard it coming out of taxi cab windows. I was thrilled to be part of it!” The album bowed on the Billboard 200 the week ending 16 June 1979 where it would climb to #14. A week later, it debuted on the R&B albums chart, subsequently reaching the Top Ten. Most impressive of all, The Boss would earn Ross her very first gold album.

Critics were unanimous in praising the singer’s third outing with Ashford & Simpson. “Ross’ best album in years,” wrote Billboard. “The horn and string arrangements by John Davis, Paul Riser, and Robert Mounsey provide the right settings for Ross’ velvety vulnerable vocals” (9 June 1979). The Los Angeles Times agreed, calling the set “one of Ross’ best albums. While The Boss serves as a good framework for her ability to convey both sensitivity and bravado, it’s the indelible stamp of Ashford & Simpson that distinguishes it from the first track to the last” (2 September 1979).

Stephen Holden, one of the album’s biggest champions, penned two high profile critiques, calling The Boss “a beautifully proportioned pop-soul showcase” in his essay for The New York Times (21 October 1979). Writing for Rolling Stone, he stated “The excellent, custom-made tunes by songwriters/producers Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson underline the renewed joy and self-reliance that infuse Ross’ singing on The Boss” (9 August 1979).

While “The Boss” made the Top 20 on both the Hot 100 and R&B singles chart, the album itself topped Billboard‘s “Disco Top 80” for two weeks beginning 25 August 1979, with “No One Gets the Prize”, “I Ain’t Been Licked”, and “It’s My House” getting a fair amount of club play alongside the hit title track. Ashford & Simpson continued their reign on the disco chart when key cuts from their latest Warner album Stay Free (1979) supplanted The Boss from number one for two weeks in September 1979.

Songs like “Found a Cure”, “Nobody Knows”, and “Stay Free”, not to mention “The Boss”, exemplified Ashford & Simpson’s more thoughtful approach to disco. “We were trying to figure out how we can put ourselves into this new beat and not be mindless … and not disappear,” Simpson chuckles. “When the groove changes, sometimes people just move on. I think that was the challenge of what the disco era was to us, and even doing songs for Diana that were like that. You don’t want to give her something that’s going to [wipes hands] in no time.”

Ashford & Simpson’s keen instincts for themselves and for their work with Diana Ross produced songs that transcended the era. “People are always going to want to dance,” Simpson continues. “If they can get a melody and a thought and something that is uplifting while they’re moving, then it has a chance to last. I think we gave Diana that. She can continue to sing ‘The Boss’ and people still refer to her as ‘the Boss’. Those kinds of things add weight to your character.”

Forty years later, The Boss is essential to appreciating the full breadth of Diana Ross’ legacy. “There’s some good stuff on there,” says Francisco Centeno. “Ashford & Simpson could always churn out a good pop song, but still have that story there.” Those stories have been told on some of the biggest stages in the world as Ross continues to include songs from The Boss in her repertoire, whether using “All for One” to close her historic 1983 “For One and For All” concert in Central Park or delighting audiences with “It’s My House” at recent shows.

Artists as diverse as John Mayer (“It’s My House”) and Whitney Houston (“The Boss”) have performed songs from the album over the years while artists like the Braxtons and Kristine W have each recorded hit versions of the title track, not to mention Ashford & Simpson’s own rousing live rendition of the song. DJ’s still keep The Boss in heavy rotation. “One of my wife’s favorite records is ‘No One Gets the Prize’,” says Ray Chew. “One of her favorite things to do, as a release and an outlet, is go to a club when Louie Vega’s spinning and dance all night. ‘No One Gets the Prize’ is a big club record still. She said they’ll bang that thing all night. The crowd loves it.”

The album’s influence on DJ’s has also endured for the past four decades. Beyond Jimmy Simpson and engineer Mike Hutchinson’s original extended mix of the title track, “The Boss” has been remixed by notable club figures like David Morales for Ross’ Diana Extended (1994) project plus Dimitri from Paris on Defected’s Dimitri from Paris in the House of Disco (2014) collection. In April 2019, “The Boss” earned Ross the seventh number one club hit of her career when Eric Kupper’s “The Boss 2019” remix topped Billboard‘s Dance Club Songs chart.

“The Boss 2019” is just one of several reasons Ross is enjoying 2019. She kicked off her year-long “75th Diamond Diana Birthday Celebration” with a residency at Wynn Las Vegas and a performance at the 61st Annual Grammy Awards in February 2019. On 26 March 2019, the singer’s actual 75th birthday, movie theaters across the U.S. screened “Diana Ross: Her Life, Love and Legacy”, an exclusive theatrical presentation of Diana Ross: Live in Central Park produced by Ross and Meteor 17 in conjunction with Fathom Events.

Those who worked with Ross all throughout her career applaud the singer’s achievements as a groundbreaking artist. “She’s like the Queen of England,” says Paul Riser. “Oh, yes. She is truly a star. She has class. When she’s 90, she’ll still have that class.” Douglas Kirkland adds, “I have always loved Diana. She was a superstar but straightforward and unspoiled. She knew how to play to the camera. Working with Diana was always an uplifting experience. We created wonderful images together.”

Ashford & Simpson were pivotal forces in shaping Ross’ path as a solo artist, if only because they wrote and produced two of her earliest and most celebrated hits, “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” and “Reach Out and Touch (Somebody’s Hand)”. The fact that they also reenergized the singer with a fresh sound on The Boss, nine years after producing her debut, attests to the special dynamic Ross shared with the duo. Ashford could translate the singer’s hopes and desires to song lyrics. Simpson could find chord progressions that mirrored her emotions.

“On that album, it felt like she was released and really let herself go,” says Ray Chew, who also worked closely with Ross when she signed with RCA Records. “She was free to do a little bit more. It had a very long-lasting mark in her career as well as Nick and Val’s career, and in mine. They were all great songs. I’m really proud to be a part of that.”

“We caught Diana at different places where she needed to say something different each time,” Simpson concludes. “I think one of her greatest strengths is a quality in her voice that’s very recognizable. She has a range that people aren’t necessarily aware of all the time, so she can be a surprise. She lives to entertain. She’s a real trooper. She’s a real performer.” And she is, now and forever, the Boss.

- The Story of a Soul Survivor: 'Private Dancer' at 25 - PopMatters

- Have Fun: A Tribute to Diana Ross, Nile Rodgers, and the CHIC ...

- Diana Ross: blue - PopMatters

- Diana Ross: Supertonic: Instrumental Mixes | Music Review - PopMatters

- Making a Masterpiece: An Interview with Legendary Composer Valerie Simpson - PopMatters