While Christopher Smith’s thriller Detour (2016) falls under the heading of genre cinema, it walks a different path to the Insidious franchise. Yet as the interview with the aim of discussing his new thriller commenced, a momentary detour to address his qualms with an alternative kind of genre cinema was taken — one that would resurface in the course of our conversation. “I was just looking at this crazy picture on the wall that looks like something out of every one of those Insidious (2010 -) horror movies, where there’s just a little dolly,” said Smith. “I’m so done with horror movies that are just a doll, a record player. Oh geez!”

Detour is the story of law student Harper’s (Tye Sheridan) precarious agreement with con Johnny Lee (Emory Cohen), who offers to murder his stepfather. Contrasting with his horror films Creep (2004) Black Death (2010) and dark comedy-horrors Severance (2006) and Get Santa (2014), Smith’s latest is most associated with 2009’s Triangle — two films that are thematically structured around the beginnings and repetition of a cyclic narrative.

In conversation with PopMatters, Smith reflected on his aspirational origins and the inevitable permanence of being a student of film. He also discussed the need to stay within yourself, and to be selective in the voices or responses one listens to, and how the artist is forever in pursuit of one’s best work.

Why a career in filmmaking? Was there an inspirational or defining moment?

Genuinely my inspiration was simple, as for most people my age: I queued up for three hours to see Star Wars (1977). Then watching the making of and special effects I remember thinking it was probably the coolest job ever because you could just hang out with C-3PO every day. This was back in the day when the only people that made movies were people in Hollywood, and I think that’s what gave me the bug for films. I thought everybody collected the film magazines and watched every single film they could get their hands on until I realised that this wasn’t the case.

Yeah, that was the start of a passion that just eventually led to me saying: “You know what, the only thing I’d ever want to do if I could choose, would be to make films.”

From film to film, how has your perspective of the process changed? Filmmakers have remarked to me that it is a constant learning curve. Is it similar to putting together a jigsaw puzzle?

Not even a jigsaw puzzle. Scorsese has said the most eloquently that we are all film students, and it’s absolutely true. I’m doing a commercial next week, and the issues raised from simultaneously filming and writing a song with the musician, creates a whole other set of problems. So there are no two things the same. You are learning all the time. I think that what you learn for yourself is what works for you, and you also become very critical. I certainly become critical of seeing things that are very easy to achieve, that seem to get very good notices in reviews.

But all of those things that are very difficult to do and are even hard to approach, like the best art house cinema where very little is happening, and yet somehow you are just gripped in this weird trance that’s hard to pull off. It fails spectacularly when it’s not done well, and so I’m always impressed by people that do what’s trickier.

Filmmaker Alfonso Gomez-Rejon told me: “The medium and the mystery of the process is that I could wake up one day and not know where to put the camera. Not that I know where to put the camera now, but you walk in with a certain sense.” Could we describe the filmmaking or creative process as a void of apprehension and uncertainty?

Well I think that goes back to the question of a friend of mine, who I always thought would be a writer. He said: “I don’t want to be a writer, not while there’s Dostoevsky.” He mentioned all of these classic Russian writers. “I’ll never be that good!” “No, you’re going to be better than these guys,” and he said: “It doesn’t matter, some people are buckled by the weight of everything, and some it seems have had no thought on anything.”

I think the more you uncover and learn about a film, the more that void of apprehension exists. I usually find that by the time you get there on that first day, you have done so many things to gauge it, that unless you have a budget that allows you to continue to have voids of apprehension, you shoot. Then very quickly you realise if you’ve made a mistake there’s still a chance to change that.

I do feel, without being too pretentious, like the painter on the canvas, you can always paint over it if you need to. But the film you’ve made is already not good enough for what you have in your head next. Your best film is going to be your next one, like Prince being interviewed about his favourite song said, “The next one.” He was being vague, but he’s right because if you think you’ve done your best work…

God, I literally haven’t started making films yet. I feel like I haven’t scratched the surface of what I want to do in terms of liking what I’ve done. I really like this film and what I would now do differently with this one is very little, but that’s not to say that it’s right. It’s perfect only in as far as it is for me because you can only reach for what you’re reaching for, and that’s the key to it.

You remarked that you’re tired of horror…

No, sorry I misrepresented myself. I’m not tired of horror. I don’t think I’ve even started making horror movies yet. I feel the other way, I think horror has become utterly boring. That’s not to say that the horror genre is tiring to me, but everybody has got to pull their socks up a bit and start to dig a bit deeper. The stuff that is being churned out and that people are turning into blockbusters is mostly utter shit and it’s just about finding a way to move on from that.

I thought of this idea just after doing Triangle (2009). Bizarrely, this film was conceived before Black Death and Get Santa. It was in a period that I was thinking a lot more about structure and I think people like to be surprised when they go to the cinema — I certainly do. I look back now and if you had to think about genre movies of any kind, the last two great American films, and I’ll stand by this with any film that has come since, are Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Se7en (1995). Those are perfect movies and I don’t think there’s anything since that has even come close to them — the pleasure of watching those films and the craftsmanship of the people that made them.

So I’m excited to come up with something, and I’m actually writing a horror movie at the moment that’s hopefully going to be the best horror movie ever. We’ll see where it ends when I finish it, but anyway, that’s my ambition.

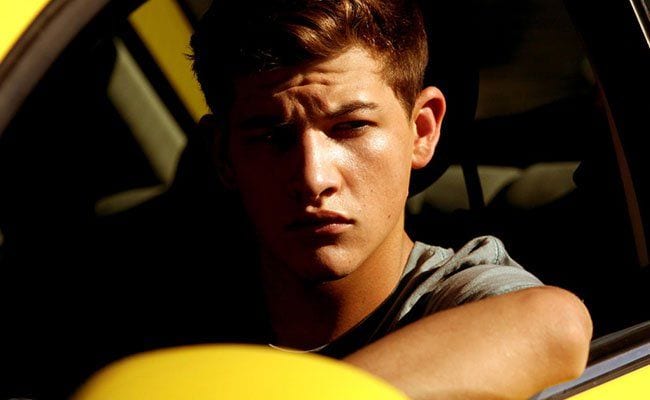

Christopher Smith on set with Tye Sheridan Emory Cohen (publicity photo courtesy of TeamPR)

Detour and Triangle are both centred around the Buddhist idea of the difficulty of escaping a cycle that permeates our existence. But whereas Detour is about choice, cause and effect, perhaps the creation of a cycle, Triangle is about the repetition of a pre-conceived cycle.

I’m really glad you say that because you’ve said it much better than I could. A friend of mine said: “It’s Triangle made easy” and I said: “No you fucker, it’s a lot more than that.” It’s actually that he’s now in that cycle — he’s basically now Jess (Melissa George) at the end of the movie. It’s a prequel dude [laughs]. I don’t say that glibly.

What you say about the Buddhist cycle, it frustrated me making Triangle — which was very much an experiment — and for me to even know how it would all sit together. We hardly deviated from the script on that film, but the central protagonist sucks up every bit of the camera because you’re always with her. I wanted there to be more opportunity to meet and to spend a little more time with the other characters. I have now achieved that, but I couldn’t achieve it to the same level back then. So I think part of the notion of Detour was to right that wrong. Not that it was wrong, but to show that I could make you interested in those other characters, even though you are viewing them in a structural way.

The verbal is a striking characteristic of the film, sharp dialogue that takes us into cinemas past, albeit it is not reflective of the way we talk in everyday life.

Absolutely, and I joked about this with the cast when we were making the film. When he’s in the lift and he says: “I’m going to get the car. I’m going to drive and keep on driving,” it’s utter nonsense. No one speaks like that in real life. In real life she’d go: “What? Where are you going?” It’s overwrought and looser movie dialogue from the old days, and I liked that.

Cinema needs to be a representation of reality and not its mirror image, or at least it’s important that there is a branch of cinema that allows us to reimagine reality.

I totally agree, and I’m really thrilled that you say that because I read a review in America that asked where we were coming from with this dialogue. Well we are coming from a place of absolute fantasy: we are coming from fiction. This is a guy or kid behaving in a way that they would in the ’40s. It goes back before this, but with the Brando model and Elia Kazan when you were starting to dig into the dock lands and the way people are really supposed to behave, and the old gnarly kind of Lee J. Cobb character, there are still traces of the old cinema in that.

So I agree with you, but I would go so far as to say there’s a new version of that, and some of the worst examples are not in the dialogue or even in the world that has been created. It’s in the overall way that many of the big films are directed, where you’re not feeling anything that is to do with the story, you’re just feeling: Why are we watching this 17-minute tracking shot? There’s no reason to understand why you’re seeing it and I think that’s partly the problem we have.

But going back to your point, I totally agree with you, but it still happens. I’m going to watch the new Twin Peaks season tonight, a world entirely created out of realism, and the Coen brothers are great at doing that as well.

Interviewing Agnieszka Holland I asked her: “Across the decades, the feel of film has changed. For example, the American gangster film of the ’40s has a different feel to the gangster film of the ’70s onwards. Do you believe this shift is caused by more than technological developments, and may reflect a changing aesthetic?” She offered: “I think it is something that is more mystical — a mystery that is included in the particular film, and which doesn’t age.” What are your thoughts on this change of a sense of feeling?

I think that’s true, and it’s as clear and present as looking at modern art, to see what’s happened over the last 100 years. It’s exactly the same. I do feel cinema is at quite a low point. I don’t think any of the films you watch now are Oscar films or are anywhere near as good as they were 15 years ago, with the exception of a few. So I don’t know whether that’s the cycle that we are in or whether it will change.

In terms of whether it spiritual, with Triangle I thought I was making a movie that no one else would be doing. You then find out that at the same time there were a number of films including Moon (2009) that were all dealing with the idea that you are the baddie. Everything comes from the news and we’re all watching the same things. So the spiritual quality is if you look at horror during the Vietnam war, we had Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and lots of very violent movies, and then during the second Gulf War we had ‘torture porn’.

Eventually, that gives way to who is responsible for that war. Are we the good guys or are we the bad guys? That ends up in lots of genre cinema, and so how it morphs is the key. Whether it’s spiritual, whether it moves viewers — but I think it’s more basic — it just moves with society.

German filmmaker Christoph Behl remarked to me, “You are evolving, and after the film, you are not the same person as you were before.” Do you perceive there to be a transformative aspect to the creative process?

A hundred per cent. People say: “Oh your films are changing” and blah blah blah. Are they getting better? I think there’s such a change, but weirdly there’s a visceral honesty to Creep that I will not do again because I’ve changed from film to film, and grown older. So you change because of the things you’ve seen that were an incredible strength in what you’ve just learned, whether it’s working with actors or the way you worked on a script. So you adjust to what you learn and what you perceive you want to do next.

But you shouldn’t second guess what you think people want, and you certainly shouldn’t respond to critical appraisal. You should only respond to what you think and then how much other people like that film. The reason I say this is because the films that have been the most critically well received, will be a film that no one knows. You say: “I also did Severance (2006) and Creep (2004)”. Creep! That’ll be the one they will remember. So to chase your tail following what you think you should do to be a filmmaker, which I did a little bit of when I was younger, has now changed to just wanting to make stuff that I think people like, and I like. So yeah, I’ve permanently changed.

Detour is available to own on DVD in the UK courtesy of Bulldog Films.