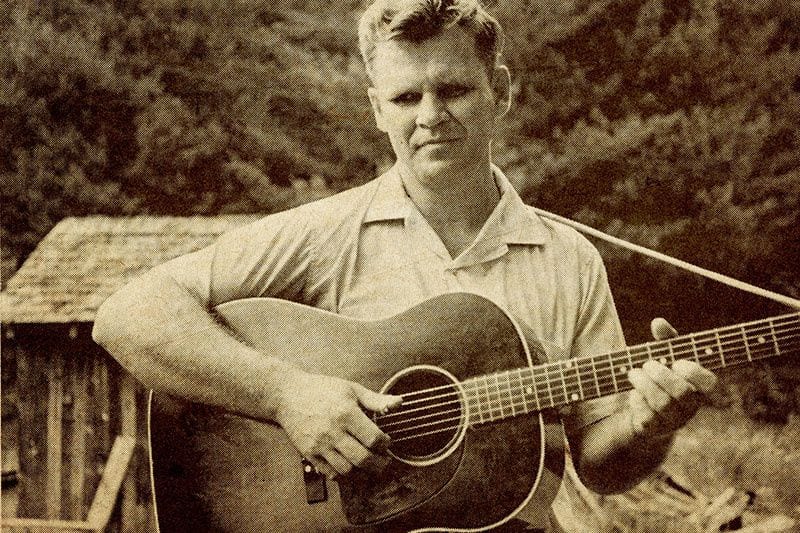

Everybody loved Doc Watson. The North Carolina musician had an engaging personality, played the guitar and other stringed instruments with felicity, knew a repertoire of songs and stories from the South learned from his family and old records by acts such as the Carter Family, and had a welcoming voice that bade one to set down a spell and listen. He was a huckster of a sort, pretending to be more of a hick than he actually was. He’d complain about “big time words” and use folksy language and tell quaint stories to bolster his old-timey credentials, but his self-deprecating behavior was meant to entertain more than fool anybody. The joke was always on him.

Watson died in 2012 at age 89. He released more than 50 studio and live albums by himself and paired with others, not to mention about two dozen compilation records. Yep Roc Records and the Southern Folklife Collection has jointly issued Live at Club 47, originally recorded in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1963 at the beginning of his career. The 9 February release date celebrates almost 55 years to the day of the original show.

This performance predates Watson’s breakthrough gig at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival and occurred before his debut solo album on Vanguard Records in 1964. Watson talks to the crowd and seems willing to change his set to please individual requests, but one suspects he’s a professional doing what he wants and just pretends to be amenable to get the audience’s applause. He has a lively conversational style that charms. His between-song patter and introductions to the material reveal he’s not above telling tall tales mixed with the truth to keep listeners attentive.

However, it’s Watson’s playing that stands out here. His finger-picking on story songs such as “The Worried Blues” and “Little Margaret” overshadows the narratives because of his dexterous style. “I believe that guitar can sing it better than I can,” he remarks during “Sitting on Top of the World”, and the audience laughs in agreement. He clearly loves to pick, as he mentions to the crowd, and lets his fingers fly even when he appears to forget the words. His instrumental performances on Merle Travis’ tricky “Blue Smoke” and the traditional “Deep River Blues” show his mastery of the guitar.

While the Club 47 gig was early in his professional career as a solo act, he was already 30 years old and a veteran musician who had already performed for live audiences for a decade. He took advantage of what Pete Seeger called “the great folk scare” of the early ’60s by focusing on old-time music more than the dance music that he played during the previous decade. There is no doubt Watson had rural roots, but as his spiels on this performance reveals, he milked it for all it was worth. He was much more sophisticated than his persona suggests.

Live at Club 47 documents a time when musicians such as Watson would claim authenticity through playing acoustic instruments and singing story songs about a simpler time. This music found an audience who rejected modern living and yearned for an earlier period in the nation’s past. The conservative nature of this desire belies its radical stance. This was not a cry to make America great again, but an acknowledgement that the present was problematic. Hearing it again today recalls a more innocent time when audiences craved a more innocent time. The music still serves that purpose. Despite all the Doc Watson material available, this album is a welcome addition to the musician’s legacy.