For a place surrounded by rocks in the middle of nowhere, the Dragon Inn gets an awful lot of customers, and a lot of awful customers. A party arrives to commandeer the whole place, and when their hired porters ask to be paid, the poor fools are promptly slashed to death. Perhaps that’s a signal to the inn’s employees not to expect tips.

Such is the opening gambit of King Hu’s 1967 martial arts blockbuster Dragon Inn (Long men kezhan), also commonly called Dragon Gate Inn. The whole plot is a variant of “a guy walks into a bar”, or rather a swordsman walks into an inn, a trope Hu had exploited so admirably in his previous film, Come Drink with Me (1966). After that popular hit, Hu left the Shaw Brother’s Hong Kong studio in favor of Taiwan, where he felt he had a freer hand in making the kind of meticulously detailed historical action film he envisioned. The results paid off handsomely, as Dragon Inn proceeded to slice a phenomenal swath through the box office.

Now it’s finally here in a restored version from Criterion, not long after the recent releases of A Touch of Zen (1971) and Legend of the Mountain (1979), two extraordinary and extravagant movies that move into the realm of personal poetry, although they were much less successful at the box office. Dragon Inn, therefore, represents King Hu’s commercial apotheosis, the bridge between his popular hits and the more individualized path he’d continue to blaze with diminishing commercial results.

Virtually the entire action takes place in that large, specially constructed, two-story wooden inn, with the rooms balconied around the giant public space. It’s like the set in Come Drink with Me, only larger and sturdier. This type of inn became common in martial arts films, in parallel to the barrooms in westerns. And like the westerns, a self-possessed stranger who knows how to take care of himself thinks nothing of sashaying into the middle of trouble.

The bad guys are all eunuchs of the Eastern Depot, a sort of sword-wielding secret police of the Ming Dynasty. Hu would use them often as his villains in order to protest against organized authority and despotism. In a bonus discussion by author Grady Hendrix, he links the film’s overwhelming success with this rebellious or anti-authoritarian element, especially in the ferment of Hong Kong’s 1967 riots against its British rulers.

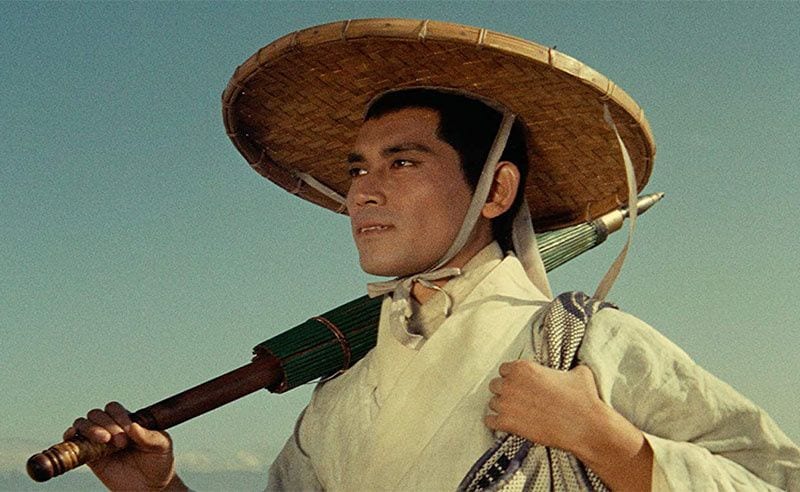

The self-possessed stranger isn’t exactly the man with no name, as in Sergio Leone’s Clint Eastwood westerns of the same era, but rather a wandering mercenary Xiao. All smiles and with infinite decorum, he deflects all attempts to kill him via poison, arrows, daggers and swords, and without breaking a sweat. He’s something of a superman played by Shih Chun, who would play much more confused and feckless scholars in Hu’s later films.

Fully his co-star is Shangkuan Ling-fung as the very petite and deadly Zhu, a woman whom most of the other characters mistake for a young man by the way she’s dressed. She’s traveling with her chubby, hot-headed brother (Hsieh Han) and is clearly both the brains and the better fighter of the two. Whereas Come Drink with Me had introduced a woman warrior played by Cheng Pei-pei, that heroine got sidelined for most of the picture while supporting the real hero. In Dragon Inn, the swordswoman is nobody’s second fiddle and pulls far above her weight. Hsu Feng, who would play fierce women in later Hu epics, can be glimpsed here in a minor role.

The story is truly unimportant as the plot unfolds its carefully calibrated series of battling setpieces presented by Hu with a combination of lightning cuts and gracefully tracking camera moves. Hendrix analyzes the techniques employed in the sequence where Miss Zhu takes on a dozen or so minions on her way to confronting a chief baddie (fight choreographer Han Ying-chieh). Hu uses everything from undercranking to trampoline leaps, with some techniques lifted from Japanese samurai films. Later, the even bigger baddie (Bai Ying) will arrive for the last showdown in the mountains.

Yes, it’s a fight movie and nothing more, which is like saying a ballet has a lot of dancing. There are people who go for that sort of thing and people who don’t, but nobody can say Hu isn’t presenting a master class in cinematic kinetics that alternates slowly simmering scenes with the promised leaping and slashing. Indeed, you might finish the film feeling as wound up as if you’d been making those leaps yourself.

Hu would make better movies than this, but perhaps none that so satisfied his action audience. This landmark of Chinese cinema was directly remade at least twice and functioned as the film-within-the-film of Tsai Ming-Liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003), where it serves as a valedictory symbol for Chinese cinema during the closing of a theatre.

Criterion’s Blu-ray supplements the 4K digital restoration with the aforementioned analysis by Hendrix and interviews from Shih Chun and Shangkuan Ling-fung. The latter explains how she went on to study many forms of martial arts and star in countless action movies. Unspoken is the implication that most of them don’t seem to have applied the same aesthetic and historical care that Hu lavished on his projects.

Hendrix notes that the film didn’t do well in Japan, by exception. Another place it couldn’t have been seen is mainland China, including Hu’s hometown of Beijing. At this time, China’s Cultural Revolution would prevent any films from being shown or made that weren’t related to Madame Mao’s Eight Model Dramas. Knowledge of this cultural convulsion must have contributed to Hong Kong’s colonial violence and Taiwan’s anxieties. It was a time crying out for maverick heroes. Like all times.