“National cinemas” is a central concept in film studies. At a broad level, it is a useful and effective device for discussing differences between groups of films made in particular times and places. Theoretically, it is given weight by the role that national states have played in developing cinematic traditions and movie industries in many parts of the world. However, like many frameworks for generalization, the idea of national cinemas starts to fray at the edges the closer one looks at individual films and filmmakers. The work of Japanese writer-director Akira Kurosawa is a strong case in point.

On the one hand, it is easy to code Kurosawa’s films as “Japanese”. His best known works are historical period pieces redolent with characters and landscapes that appear to be so very culturally and geographically specific: samurai, Buddhist temples, light dappled forests. So, too, with recurring themes: honor, duty, fealty.

On the other hand, beneath the surface, it is possible to see Kurosawa drawing from a cultural heritage that is more global than national. He adapted and borrowed from various “Western” literary and cinematic figures, including William Shakespeare, John Ford, and Dashiell Hammett. From the other side, his works have inspired and been adapted by “Western” filmmakers such as Sergio Leone, Sam Peckinpah, and George Lucas, as well as influencing Hong Kong action cinema. Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel, recently released in a new DVD version by the Criterion Collection, highlights the blurriness of the boundaries between national cinemas.

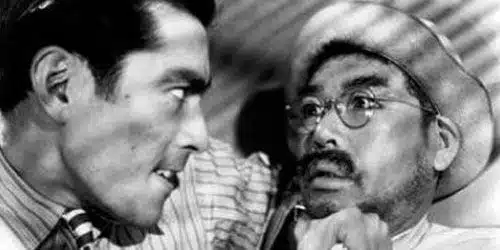

Initially released in 1948, Drunken Angel is set in a Tokyo neighborhood immediately after World War II. The central feature of this district is a sump or bog. Bubbly, murky, full of waste and bacteria, the sump is a powerful signifier for the neighborhood as a whole as its residents struggle to survive against the challenges of resource shortages, disease, and domination by organized crime. As the central character, Dr. Sanada (Takashi Shimura), tells his gangster patient, Matsunaga (Toshiro Mifune), the bog represents all of the “scum” surrounding the young, TB-ridden yakuza, holding him down and keeping him from healing. Sanada’s fight to get Matsunaga to adequately care for himself, both in terms of his illness and the way he lives, drives the film’s narrative.

The dramatic tension rises palpably with the arrival of Okada (Reizaburo Yamamoto), formerly in charge of the neighborhood now managed by Matsunaga. Okada’s return also poses a threat to the doctor’s female assistant, Miyo (Chieko Nakakita), who had some kind of unspecified, but clearly abusive, relationship with the older gangster before he was sent to prison. The movie culminates in a showdown between the two yakuza.

As noted by more than one of the contributors to the supplemental features included with the new disc, and notably by Kurosawa himself, Drunken Angel is often cited as the writer-director’s “first film”. This is not a literal statement, Kurosawa had already directed some seven features before Drunken Angel, but a figurative one, implying that it is the first film over which Kurosawa believed he had true authorship. And, indeed, the movie exhibits a number of qualities typical of his subsequent work.

There are, initially, the flawed protagonists of Drunken Angel. The title, in fact, refers to the doctor, who is an unapologetic alcoholic. His work in a down trodden part of the city is presented as the result of both an instinct towards serving the poor and the marginal and the good doctor’s alcoholism. Unsurprisingly, Matsunaga is a conflicted and conflicting character. Even his final decision to throw himself to the wolves can be read more than one way, as equally noble and ignoble.

Complicated heroes and deeply flawed central characters populate virtually all of Kurosawa’s later films, and particularly touchstone works like Rashomon (1950), The Seven Samurai (1954), Yojimbo (1961), and Ran (1985). Drunken Angel also shares with these films, Rashomon excepted, implacable, far less ambiguous villains for its flawed protagonists to face.

Throughout the film, Kurosawa, photographer Takeo Ito, and art director Takashi Matsuyama play with light and shadow. Characters continually move into one and out of the other, and, as in Sanada’s and Matsunaga’s first scene together, are sometimes bisected by light and dark. The careful use of light and shadow to signify qualities and complexities of character, and moral choices, is a persistent visual trope in Kurosawa’s work, one that also contributes to the distinctive look and feel of his films. Indeed, his movies often seem to be worlds unto themselves, and this is no less true of the gritty, contemporary Drunken Angel than it is of the fairy tale-like The Hidden Fortress (1958).

The Hollywood influence on Kurosawa is evident in Drunken Angel on a number of levels, including the costumes, especially the zoot-suited gangsters, the noirish urban setting, and the inclusion of musical production numbers. Indeed, like all Hollywood gangsters, the yakuza in Drunken Angel hang out in a dance hall-cum-night club, the perfect setting for breaking out into song and dance.

The carefully selected and produced extra features included with the new Criterion Collection DVD all intelligently locate the film within its time and place and in the context of Kurosawa’s filmography. The disc includes a booklet featuring an essay by Ian Buruma and excerpts from Kuroawa’s own Something Like an Autobiography (Vintage, 1983).

In addition to a commentary track from scholar Donald Richie, the DVD itself includes two supplemental pieces. One, “Akira Kurosawa: It is Wonderful to Create,” is part of a series on “Toho Masterworks,” and is originally from 1998. It focuses on discussions with and about Kurosawa and the long term collaborators with whom he worked for the first time on Drunken Angel, chiefly Mifune, art director Matsuyama, and composer Fumio Hayasaka. The other, “Kurosawa and the Censors,” is a talking head documentary short featuring film scholar Lars-Martin Sorensen. The subject of this piece is the role that American censors and the attempt to re-engineer Japanese society after the War played in the production of Drunken Angel.

Sorensen reviews censor notes on various versions of the story and scripts for the film and discusses how Kurosawa reacted to and dealt with these notes. This feature places the issue of national cinema, and Kurosawa’s “Japanese-ness” in a unique light, as it shows US government control over another country’s film industry occurring at a level far beyond that ever asserted at home.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of Criterion Collection DVDs is the treatment of film as a form of art worthy of serious criticism and contextual examination. Richie’s commentary track is richly interpretative, moving from discussions of post-War Japan to Kurosawa’s body of work, and back to Drunken Angel itself. As it happens, Richie is able to speak about the film both from a more detached academic perspective and from first hand observation of the film shoot.

Interestingly, Richie and Sorensen offer radically different interpretations of the movie’s ending, wherein a ray of hope is brought to the film in the form of a 17-year-old school girl (Yoshiko Kuga) Sanada had been treating for TB, but who appears to have fought off the illness. Richie sees this ending as being consistent with other choices made by Kurosawa over the course of his career, and notably in Rashomon, while Sorensen sees it as false, at least as much a product of the censorship regime as it is from Kurosawa’s artistic vision.

Presenting these kinds of discussions of their selections is one of the primary values of a Criterion DVD. Another is in the attention paid to the film-to-DVD transfer. While hardly pristine, the newly restored and digitized film is bright and clear, and the sound quality is excellent.

One need not know much about Japanese national cinema or Akira Kurosawa or post-War Japan to enjoy and appreciate a film like Drunken Angel. Knowledge of the film’s historical and artistic contexts will enhance one’s appreciation of the movie and open up new ways of seeing the film, but its basic artistry, dramatic power, and eminently translatable narrative are perfectly capable of standing virtually alone. Whatever one’s interest in seeing the movie, the new Criterion Collection edition allows viewers to experience Drunken Angel on multiple levels.