In Eating Animals, a new documentary based on the 2009 book by Jonathan Safran Foer, filmmaker Christopher Quinn explores the implications of our country’s unhealthy appetite for factory-farmed animals. The film takes an all-angles approach, featuring insights from vegans, vegetarians, foodies, and farmers, avoiding the preachy, righteous tone found in most food docs of its ilk.

Natalie Portman narrates as we’re given glimpses at some of the harrowing, inhumane practices that have tragically become commonplace at factory farms across the nation, as well as an in-depth look into the lives and minds of farmers who fight to preserve the farming philosophies that helped build this nation, raising animals humanely, sustainably, and most of all, lovingly.

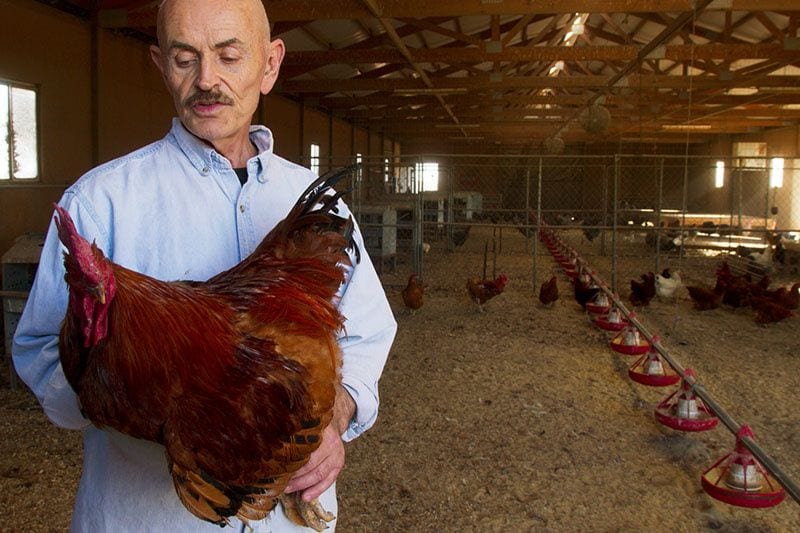

One of those farmers, Frank Reese, owner of Good Shepherd Poultry Ranch, speaks to PopMatters along with Quinn to discuss the movie’s unique brand of activism, the biggest misconceptions about farmers and their work, and the devastating impact of factory farms on animals, the people that eat them, and the crumbling environment around them.

Having screened the film at festivals over the past few months, have you had any conversations with audience-members who have had their eyes opened to the realities of factory farms or even considered changing their eating habits?

Reese: It’s a very personal thing. It isn’t like a regular movie. This is telling a story of something that everyone on earth has a relationship to, and that’s food. Everybody has an opinion, and they can be anywhere from “I don’t give a damn,” to “I’m just going to buy Doritos and Diet Coke, and who cares about the rest of this stuff.” And some people say, “How dare you kill an animal! Everybody on earth must be vegan!” You get this really intense reactions, and there’s no room in between.

We need to have these conversations. I’ve had conversations with Purdue [Farms], Tyson [Foods], with the individual farmers who are fighting this battle everyday. How we eat and how we approach agriculture is what this movie is about. What have we done to agriculture to feed ourselves?

Quinn: Post World War II, we had all of this new technology and hardware, and we applied it to the agricultural sector, which … diminished the independent, small American farms. There used to be a patch quilt of small farming communities all throughout the farming belt of America. Corporatized farming really changed all that. By the time the ’60s and ’70s came, it was all about cost and efficiency. We wanted cheap meat, we wanted it when we wanted it, and that was the fast food era that really changed everything. It changed the way the meat is grown, and it changed the animals themselves. All they wanted was for the animals to grow fast, and as cheaply as possible. So they manipulated the genetics of the animal through multiple mutations. So the bird that you eat from a fast food restaurant will have grown in 35 days and is ready to go to market by then.

Reese: That’s 300 times faster than normal. And that’s done not through antibiotics and growth hormones and all of the things that a lot of people think. It is what they’ve done through scientific, genetic selection. Through multiple known diseases, or rather what I call diseases, whether it be hyperthyroidism or dwarfism, mutating the obesity gene, changing the hormonal structure of the brain of the animal so that it never gets full.

Quinn: What I point out in the film through Natalie’s narration is that the accelerated growth of these commodity birds that we have all learned to love and eat is the equivalent of a two-month-old human weighing 600 pounds.

That blew me away.

Quinn: It blew me away too. After a while, I realized I’m eating a mutant bird that has dwarf genes and obese genes and hyperthyroid… all of these things that Frank just mentioned. Pretty soon, chickens start to look very different, with the exception of heritage breeds. Frank has the oldest living continuous stock of birds in the United States of America. That’s why Frank and his farm matter so much — once those genetics are gone, they’re gone.

Frank, what are some of the biggest misconceptions about farmers and the work you do?

Reese: Probably the biggest thing is that people don’t understand the difference between what I do and what people buy today [in the grocery store]. Some people think that we are still raising them in confinement or that I buy the chickens from a hatchery and raise them. That’s probably the biggest misconception. Because it’s so far removed from the norm that I actually have the [bird’s] parents and the grandparents on the farm. These animals are still produced one hundred percent naturally. No artificial insemination.

It’s hard for people to wrap their heads around because they’re so removed from where their food comes from and animal science. People don’t understand, and they don’t understand why it matters. I’m trying so hard to natural animals. Within the food industry, now they’re pushing things like fast growth, slow growth, antibiotic free, organic… none of that changes the problem. We need to go back to the normal animal.

Quinn: I’d like to think that in the film you can see how a chicken normally lives. By spending time on Frank’s farm you see a willful animal that hatches and is taken care of by the older birds, and after six weeks, you see it going out and finding food. This whole process is really important for the bird’s health and for our health.

Reese: The movie shows [how chickens looked] in 1930, 1940, 1950, and so on. You see this radical change of its shape, it’s conformation. By the time you get to 2016, it’s like looking at a balloon on these little sticks called legs.

Christopher, how did making this movie change your outlook on eating meat?

Quinn: I thought, what am I going to feed my children? I’d be happy to feed Frank’s birds to my children, but I would have a hard time feeding my family any other chicken. You’d have to eat six commodity birds to equal the nutritional value of one of Frank’s birds.

There is a lot of harrowing footage and information in the film, about practices in the factory farming industry that many of us are ignorant to or just choose to turn a blind eye to. Did you make this movie to combat the country’s general ignorance about the issue?

Quinn: I made the film so that there was a body of evidence that someone could see and draw their own conclusions from. The film isn’t wagging its finger and saying “don’t ever eat meat”. I wouldn’t want anybody to say that to me. But what I did learn is that 99 percent of that meat I wouldn’t feed to anybody. That’s a bit of a problem. So it starts a conversation of, if we’re going to move forward, how?

I like to look at the film as a road map moving forward. Even if people decide to opt out of eating meat once or twice a week, the significance on the environmental blueprint would be so significant. If that starts to happen, we’ll see a reversal of the degradation of the environment, and it’s also good for people’s health. And you wouldn’t be supporting a system that has animals suffering mightily.

Reese: The other thing is, this is not a problem or concern just for the wealthy. This affects everybody on the face of the earth. I don’t care if you’re extremely poor, rich, or any race, you should be able to have access, in some form, to the best nutrition. Everybody cares about what they feed their kids. We need to approach meat with far more concern and maybe eat it less.

I grew up very poor, and when you killed a chicken, you had to feed six, seven, eight people maybe two or three meals. How do you do that? Consider the meal as not being just the chicken. Add it to all of the other ingredients. We take great respect and reverence with our animals. When my mother would butcher chickens, she would ask for forgiveness.

But people don’t live in that world anymore. They just drive through the drive-thru at Colonel Sanders and get their bucket, or to McDonald’s to get their nuggets, or to Chick-fil-A to get their sandwich. There’s no connection to the living creature, hidden in a barn somewhere, that gets to live 36 days and is then shoved in a crate and killed.

What effect do these factory farms have on the economy?

Quinn: When you look at a cheeseburger or a fast food sandwich, they cost 99 cents, but when you externalize the cost of that actual sandwich through the subsidies, chicken is heavily subsidized by us, the taxpayer, through the government. And there’s also the factor of health care. And then you add all of the environmental damage that’s taking place, and all of a sudden, this 99 cent burger becomes quite costly.

There’s a gentleman who’s trying to figure out that price, and he’s arguing that it’s somewhere south of $100 when you add all of the external costs to it. These sandwiches are easy to get, they’re cheap, but we all pay for it in the end.

Reese: The trend started in the ’70s. The movie tracks the rise of Colonel Sanders and McDonalds and the “nugget”, and if you follow that curve and follow the curve of morbid obesity in our country, they’re exactly the same. When I was a kid going to school, we had maybe one heavy kid. Now it’s 50 percent. Our schools are overweight. I do anesthesia for a living, I’m a nurse anesthetist. I would say probably 60 to 70 percent of patients I see in surgery are morbidly obese. We’re eating more and more of these animals, but these calories have less and less value.

Frank, you’re an anesthetist?

Quinn: Frank’s a turkey farmer, but to underwrite his operation, he’s got a second job. [laughs] That’s something that I’ve learned. None of the one percent of truly independent farmers are making much money. What is that? How did we develop a system where farmers are taking all of the risk and taking the hit and corporations are profiting from it? There are a number of reasons for me to opt out [of eating factory meat], but that’s a big one. I really can’t support a system that degrades our communities in such a way.

Watching the movie made me seriously reconsider my eating habits, and I’m sure you’ve heard from people with similar reactions. A lot of people lack context when it comes to eating meat, and Christopher, I imagine with this movie one of your goals is to provide that context. The better you tell your story, the better the information is received. What was your storytelling approach?

Quinn: The first thing was that I didn’t want to make just another food documentary. Secondly, I wanted to leave the space open enough so that you could experience what was actually happening in the movie but you could also open up your mind to think about this stuff.

Reese: That’s the problem, whether people will open their minds, open their hearts, and not feel attacked.

I’m a fourth generation farmer just in Kansas — in America, we can probably go back eight or nine generations. I’ve seen the struggles of farmers. I think Christopher is taking the movie to Arkansas, and I think there, we’re going to get some of these people who are facing these everyday struggles of trying to survive and farm, raising peanuts or corn or rice or cotton or chickens or whatever. They may get angry, they may not appreciate some of the things [Christopher] is saying, but they can’t avoid the truth.

Nobody goes into farming because they hate animals. Nobody goes into farming because they want to torture animals. They just get caught up in the system.