I don’t know if it was normal for the people. But it was normal for us.

— Puchi (Jennifer Lopez)

Early in Leon Ichaso’s retelling of the rise and fall of ’70s-’80s Nuyorican salsa legend Héctor Lavoe (Marc Anthony), the singer meets with bandleaders Johnny Pacheco (Nelson Vasquez) and Willie Colon (John Ortiz) to discuss their plans. Aha, they decide, they will mix up their Puerto Rican and Dominican styles with jazz, R&B, and rock to come up with a new sound that will be called “salsa” — you know, says one, because it’s “like a sauce.” With that, the movie’s forward motion is all but quashed, as you pause to imagine studio suits insisting that El Cantante explain even this most rudimentary concept. It’s a movie about Héctor Lavoe for white people.

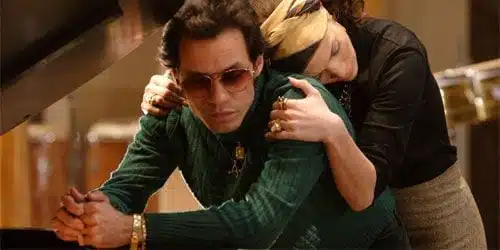

That’s not to say that explanation is in and of itself a problem. But in this instance, the biopic formula overtakes historical details and even director Leon Ichaso’s signature impressionism, with an awkward and unsurprising result. An obvious labor of love for Ichaso and producer/star Jennifer Lopez, the film recounts Lavoe’s basic arc — he moved to New York from Ponce, Puerto Rico in 1963, sang in clubs, married Puchi (Lopez), signed with Fania Records, and succumbed to drugs — using a late-in-life interview with Puchi to complicate the “facts.” In this interview (black and white, Lopez in “old” makeup), Puchi wears a nameplate necklace and resists her off-screen questioner’s suggestion that she’s misremembering, asserting upfront that it is her perspective of Lavoe’s life. “Don’t fucking get insulting,” she says, cigarette smoke curling around her perfectly lit face. “You want somebody else’s version of it, you should have had somebody else come.”

Puchi’s hostility here helps to make her something of an antagonist in the film. In her first flashback, she’s recovering Lavoe from an uptown shooting gallery, so that he can make a red carpet appearance. All business, she strides from her limo in a tight red dress, up the stairs into a broken-down tenement, and confronts her nodding husband. En route to the event, she cleans him up and offers him cocaine in order to counteract the heroin. When she dismisses his proclamations (“You always love me when you’re high”), he has a ready answer: “I’m always high.”

El Cantante‘s use of the troubled-artist-on-drugs premise (see also: Ray, Walk the Line) is mostly tedious. While the film includes frequent slow-motion, dissolvey montages to show the heat and physicality of the music (after Lavoe meets club girl Puchi, her enthusiastic dance moves tend to be showcased), it uses similar imagery to suggest Héctor’s druggy hazes. While it makes sense that in his experience, music, performance, and intoxication blur together, for viewers looking in from the outside (or more accurately, from Puchi’s perspective), these arty visuals become repetitive and not so helpfully abstract. They are more effective in Ichaso’s 2001 film, Piñero, which uses similar techniques to convey the Nuyorican hustler/poet’s mind and memories, effectively turning the biopic format inside out.

This film is more episodic and less inventive, reframing Puchi and Héctor’s tumultuous, addictive codependence as a love story that “somehow” went wrong. Though the film doesn’t press the point, this “somehow” appears to begin when she introduces him to marijuana on their first party-date (she will go on to do coke and drink with him, though she appears to worry about the smack that comes later, as this draws him away from the band and her, into dark alleyways and increasing isolation). Despite and maybe because of his addictions, “He became the voice of the people,” says Puchi.

Though Anthony’s vocals go a long way toward making this seem right, for the most part you have to take her word for it. The film shows few “people,” except as concert crowds and the several, briefly glimpsed figures who are key to Héctor’s career, including Fania founders Johnny Pacheco and Jerry Masucci (Federico Castelluccio). When they give Héctor his new last name (“The voice, in French!”), they again overexplain the moment: “Black musicians have Stax… Latin musicians are gonna have their own music label.” And so: “Bad Boys of Salsa” and “Fania Rises,” announce montagey newspaper headlines, dissolving into Lavoe and Puchi snorting cocaine in “1973.” This is as far as the film goes toward examining the movement for Puerto Rican nationalism or commercialization of the culture.

As his career takes off, Héctor descends into predictable excesses, unable to resist sex with “silly bitches” or look after their son Tito, who shows up at various ages to embody but not illuminate his dad’s failings. Her willingness to put up with all of it suggests a whole other Puchi story the film doesn’t explore (when Héctor’s sister disapproves of her, she announces defiantly that her family “sell[s] dope,” but beyond that, her background is unknown). Similarly untapped is Héctor’s plainly strained relationship with his own father (Ismael Miranda), a musician back in Puerto Rico who rejects his junkie son (“I only wanted you to be proud of me,” whimpers Héctor, in a scene that might have been taken from any number of biopics, old and recent).

When at last his career and his habit collide — he’s late once too often for a gig and Willie leaves him — the film continues to list tragedies: Tito’s accidental death by gunfire, Héctor’s commitment to an institution, diagnosis as HIV-positive, efforts to protect himself with blessed beads, and suicide attempt. He’s miserable, that much is clear, but his contexts remain murky. “You don’t like talking about what hurts you,” he tells Puchi late in the film. “That’s you. I don’t like it either. That’s us.” And that, unfortunately is also the movie. While Ichaso’s vibrant, ambiguous aesthetics can be galvanizing, here they’re used to service a flatfooted screenplay. When, in 1978, Ruben Blades (Victor Manuelle) appears on stage to perform the song he has written for his idol, “El Cantante,” the film is only marking time, almost literally. Yes, the younger star’s dedication is moving, but the point seems rather to explain the film’s title, yet another example of its distrust of viewers to keep up with a story that, even it is isn’t well-known beyond salsa and Latino communities, can speak for itself.