In 1893, Arthur Conan Doyle famously killed off Sherlock Holmes in his story “The Final Problem”. Doyle intended to write, as he put it, “better things”, but fans hounded him into bringing the detective back, first in The Hound of the Baskervilles, set before “The Final Problem”, and then permanently. It turned out that the final problem was not death, but staying dead.

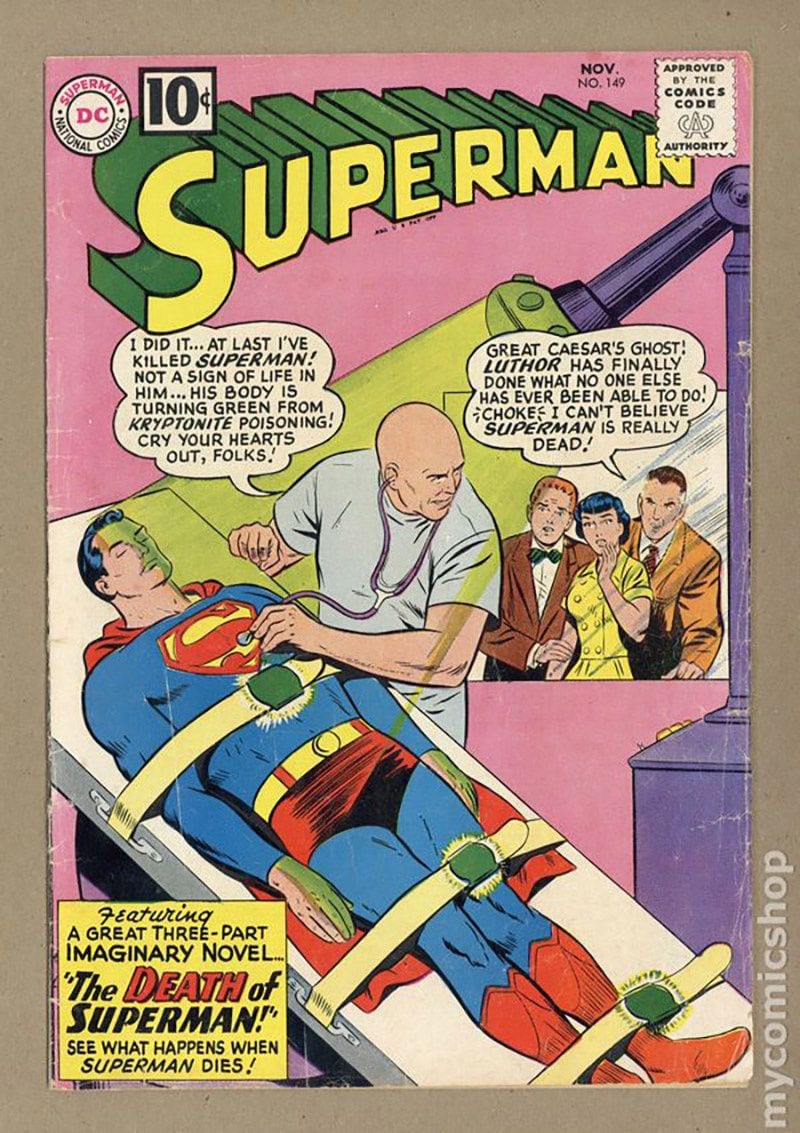

Retroactively, of course, Doyle was able to explain that Holmes did not really die. But does any fictional character? Even taking death within the story at face value, with the possibilities — relied on far more now than in Doyle’s day — of reboots, sequels, prequels, time travel, multiverses, clones, or resurrection, no one needs to stay dead for long. When Aslan dies and is resurrected in C.S. Lewis’s 1950 novel, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the adult reader recognizes the beast as a Christian allegory, since only Christ—or a suitably Christian surrogate—can come back from the dead. Yet by the ’80s, following Holmes’ lead, every character who died during the film’s climax, from alien ET to robot Johnny Five in Short Circuit, managed, after the audience cried, to come back for the resolution. Even as recently as 1992, DC Comics still managed to persuade the world that Superman was dead. Spoiler alert: He wasn’t.

Today, we expect Dr. Who to regenerate. In comics and on screen, superheroes resolutely will not stay dead, with Batman, Aquaman, Wonder Woman, Flash, Supergirl, Green Lantern, Green Arrow, Spider-Man, Captain America, Thor, and every major member of the X-Men having died and returned, along with many others. When Superman dies, again, at the end of 2016’s Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, it would be absurd for audiences to believe it, and indeed his resurrection is already implied. Along with heroes, monsters like vampires and zombies, which both enjoyed post-millennial resurrections in popular culture after a brief dormancy, famously will not stay in the ground. Even characters who don’t, strictly speaking, come back to life still manage more time. While Peter Parker’s Uncle Ben is one of the last characters who has not been resurrected, comic-book readers have seen him in alternate realities and What-If scenarios, and viewers saw him murdered on screen in 2002 and again just a decade later. Like a contemporary update of The Passion Play, Ben’s death must occur in order to teach Peter Parker, and the audience, that lesson about great power and great responsibility. Although he finally managed to stay dead in Spider-Man: Homecoming, Ben will surely be back in whatever reboot comes next.

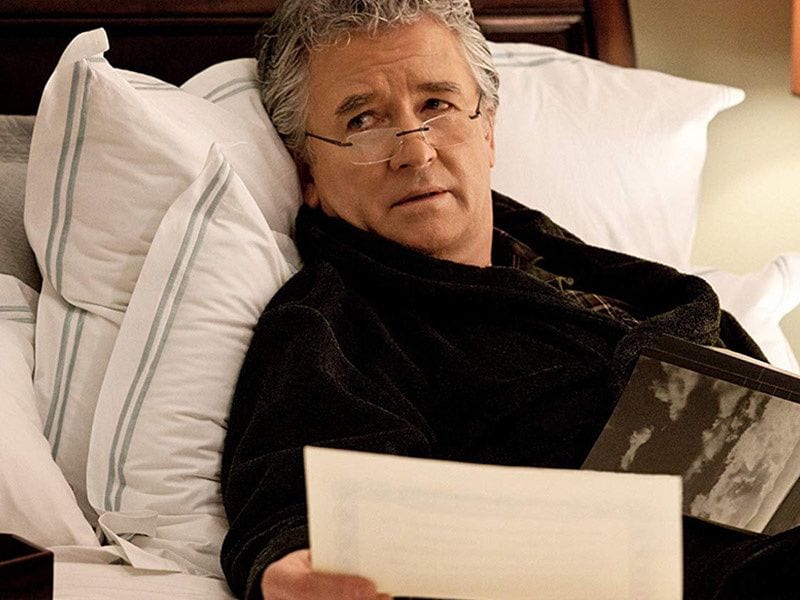

In what was the TV pop cultural event of 2016, Game of Thrones‘ Jon Snow, seemingly dead at the end of Season 5, and not seemingly but really, really dead in the premiere of Season 6, was brought back to life. Given 2016’s cultural landscape with barely a single undisturbed grave, his return should not have surprised anyone. Consider: Bucky Barnes, dead in Captain America: First Avenger, back in the sequel as the eponymous Winter Soldier; Captain Kirk, dead and back in Star Trek: Into Darkness, when in the ’80s Mr. Spock had to wait a whole movie sequel for his resurrection; Cyclops and Jean Grey, killed in X-Men: The Last Stand (spoiler alert: it wasn’t) but brought back through a rewritten timeline in X-Men: Days of Future Past; Nick Fury and Commissioner Gordon and Pepper Potts, all dead in their respective movies (Winter Soldier, Dark Knight, and Iron Man III), but then, quickly, their deaths revealed as ploys.

And, of course, Groot—Aslan in flora rather than fauna form—sacrifices himself in Christ-like fashion to save his fellow Guardians of the Galaxy but is risen before the closing credits, but cuter. With more dancing. Avengers: Infinity War has just completed its run as the summer blockbuster of 2018, ending with the deaths (Loki, Heimdall, Gamora, Vision) or disintegration (Black Panther, Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, Winter Soldier [again], Scarlet Witch, Star-Lord, Groot [again], Drax, Mantis, Nick Fury, and Maria Hill) of nearly all its heroes aside from the original film’s team. And yet I have this feeling that they might come back—as numerous commentators have already noted, Marvel has sequels slated for most of these seemingly dead characters.

Somehow, Jon Snow still surprised audiences, perhaps because, more than most fantasies, Game of Thrones operates by the realistically bloodthirsty code that any character, no matter how good, beloved, or central to the plot, can die and usually stay dead—Ned Stark, the Red Wedding, the Purple Wedding, any wedding. Still, the show had laid the magical groundwork with a previously resurrected Beric Dondarrion, and Jon’s return, as well as eventual vindication, seemed to leave audiences satisfied. At the same time, his death and life were part of the larger narrative trend that has turned into a narrative law: no one stays dead.

Other genres, of course, routinely bring back characters from the dead—soap operas, for one, have long trafficked in unlikely character returns, most famously Dallas, which brought back Bobby Ewing by revealing that his death, along with the entire 1985-86 season, 31 episodes, had all been a dream. And the superhero deaths and returns as well should not be surprising, since, like the soap opera, comic books have been serial narratives since their inception. Once back for good, Sherlock Holmes lived on to earn a Guinness Book record as the most portrayed fictional human character in film. But the word “human” reveals a technicality—Dracula is the most portrayed character of all time. Between Holmes and Dracula, seemingly as different as characters can be, we can see a similar narrative, and human, impulse: writers, and audiences, revive and revise characters to be whatever they need at the time, with death as only a minor impediment.

But despite what I just said about Game of Thrones, can we truly be satisfied with the end of ultimate death in our narratives? What does it mean, ontologically and narratively, when the seeming finality of death disappears from our stories? What does it mean when our stories and our characters, unlike our lives, refuse to come to an end? On the one hand, the perpetual life of beloved characters is obviously bound to their commercial use as properties to be serialized and franchised; Superman (or Black Panther or Spider-Man) is far too valuable to stay dead. It’s also tempting to liken the end of endings to video games. Unlike my halcyon days of three lives and running out of quarters, for decades players have had as many lives as they needed until the game is done—unless it’s never done. Does the end of endings mean that we may begin to think about television, film, and literature like video games? Deaths of characters and ends of stories work in tandem. As Walter Benjamin says in his essay “The Storyteller”, readers intuitively understand all of life through the end of the story, which represents a kind of death, or through the actual death of a character:

The nature of the character in a novel cannot be presented any better than is done in this statement, which says that the “meaning” of his life is revealed only in his death. But the reader of a novel actually does look for human beings from whom he derives the “meaning of life.” Therefore he must, no matter what, know in advance that he will share their experience of death: if need be their figurative death—the end of the novel—but preferably their actual one. How do the characters make him understand that death is already waiting for them—a very definite death and at a very definite place? That is the question which feeds the reader’s consuming interest in the events of the novel.

Human beings can never understand the full significance of our own lives, because we must live them from our singular, present-tense perspective and thus cannot reflect on our own ending. But we can objectively contemplate the full life of a fictional character, because the beginning and end of the story delineate their complete existence. And so through fiction—the figurative deaths that are stories and the more literal but still fictional deaths of characters in stories, we may apprehend death, something that by its very nature eludes our understanding, and therefore take small comfort. As Benjamin concludes, “What draws the reader to the novel is the hope of warming his shivering life with a death he reads about.” That’s meant to be up-lifting. So while it seems like a loss when our favorite characters die or our stories end, we have also gained comfort and ontological wisdom.

Or, as Frank Kermode, in his seminal book The Sense of an Ending (Oxford UP, new ed., 2000) understands it, endings help readers make sense not just of their own lives, but their place in history. Stories are not just dress rehearsals for death, but they are inextricably linked to etiological and apocalyptic sensibilities: “Fictions,” Kermode says, “whose ends are consonant with origins satisfy our needs.” The conventions of story dictate a beginning and an ending; for every “Once upon a time,” a “Happily ever after.” Kermode goes on to suggest that “one has to think of an ordered series of events which ends, not in a great New Year, but in a final Sabbath.” The endings of all stories become the endings of all things: narrative ending as a death, but also death as a narrative ending: “the End is a fact of life and a fact of the imagination” (58). But without character deaths or endings, what happens to Benjamin’s comfort or Kermode’s closure? Without Happily Ever After—or unhappily ever after, for that matter—readers are left only with a grim, relentless Middle—just like our own real lives.

Before Batman v Superman, before his 1992 almost fatal fight with Doomsday, Superman died before, in a 1961 comic billed as an “imaginary story”. Then he died again, figuratively, in Alan Moore’s 1986 preparation of DC’s character reboot. Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? (DC Comics, 1986) opened with this preface, which reads, in part: “This is an imaginary story (which may never happen, but then again may) about a perfect man who came from the sky did only good. It tells of his twilight…of how his enemies conspired against him… and how finally all the things he had were taken from him save for one.” In comics, the “imaginary story” takes place outside of cannon and continuity; like time travel, multiverses, and resurrection, it’s an existential mulligan, or maybe an alibi—it’s just a story. But I think Moore, in likening Superman to Jesus Christ no less than CS Lewis likens Aslan, means the opposite: stories matter, not despite that they’re imaginary, but precisely because they are.

Superman, of course, did not die. But then again, no fictional character really does. Perhaps the fictional prototype is less Sherlock Holmes, first written in 1887, than his contemporary Peter Pan, who debuted in 1902. Legend of Zelda’s Link looks a lot like Peter Pan. But it’s not just the pointy ears and pointy weapons, the green clothes, the shock of hair. Like all video game characters, and like Peter Pan, Link is, in essence, immortal and eternally youthful. You could make the same case for all fictional characters—that they revert to being alive and, if applicable, young when you start the book, movie, or game again. As a father, no sentence weighs heavier on my heart than when one of my kids tells me, once game time is over, that “I’ll just play until I die.” “I” die, not “Link dies” or “my game ends”.

But if Link cannot never die, if there is no final level, since the thing resets ad infinitum and there are always more Zelda sequels on the horizon, then it can also, to this adult, feel like there is also no point. Unless the games are more didactic than we give them credit for: the never-ending levels, never-ending deaths, and never-ending sequels in games provide the ironic moral that there is more to life than amassing points, more to existence than getting to the next level. The playing, the process, and the middle: they are the point. So perhaps viewers and readers should enjoy each installment, each reboot, each prequel and sequel, not because, in Benjamin’s or Kermode’s terms, the ending gives us a sense of our own life. But because, ironically, deathless storytelling gives us a strange kind of comfort. It seems to have worked for Christianity.