To the extent that Fad Gadget has any cachet in the annals of music history, it’s for being the act Depeche Mode were supporting at a small British club when Mute Records founder Daniel Miller discovered them. Even in his time, in the late 1970s to mid-1980s, Fad Gadget, whose real name was Frank Tovey, never found mainstream success. Still, he played a key part in the evolution of Mute, synthesizer pop, and industrial music, and was influential as a performer.

For the most part, Tovey’s albums have languished out of print. Even though the current zeitgeist favors synthesizers, post-punk music, and the ’80s, he has largely been overlooked. Therefore, it is exciting to hear that this vinyl reissue of The Best of Fad Gadget is but “the first stage of Mute’s celebration of Frank Tovey’s work”, as the label puts it, with a comprehensive box set to follow in 2020.

For newcomers or those who need to be reacquainted, The Best of Fad Gadget is a good place to start. Originally issued in 2001 to coincide with a circle-completing tour supporting Depeche Mode, it features 18 tracks chosen by Tovey himself. Each of the four Fad Gadget albums is represented, as well as some non-album sides. Nearly all of the seminal tracks are here. It isn’t everything, but it might just be everything one needs to know.

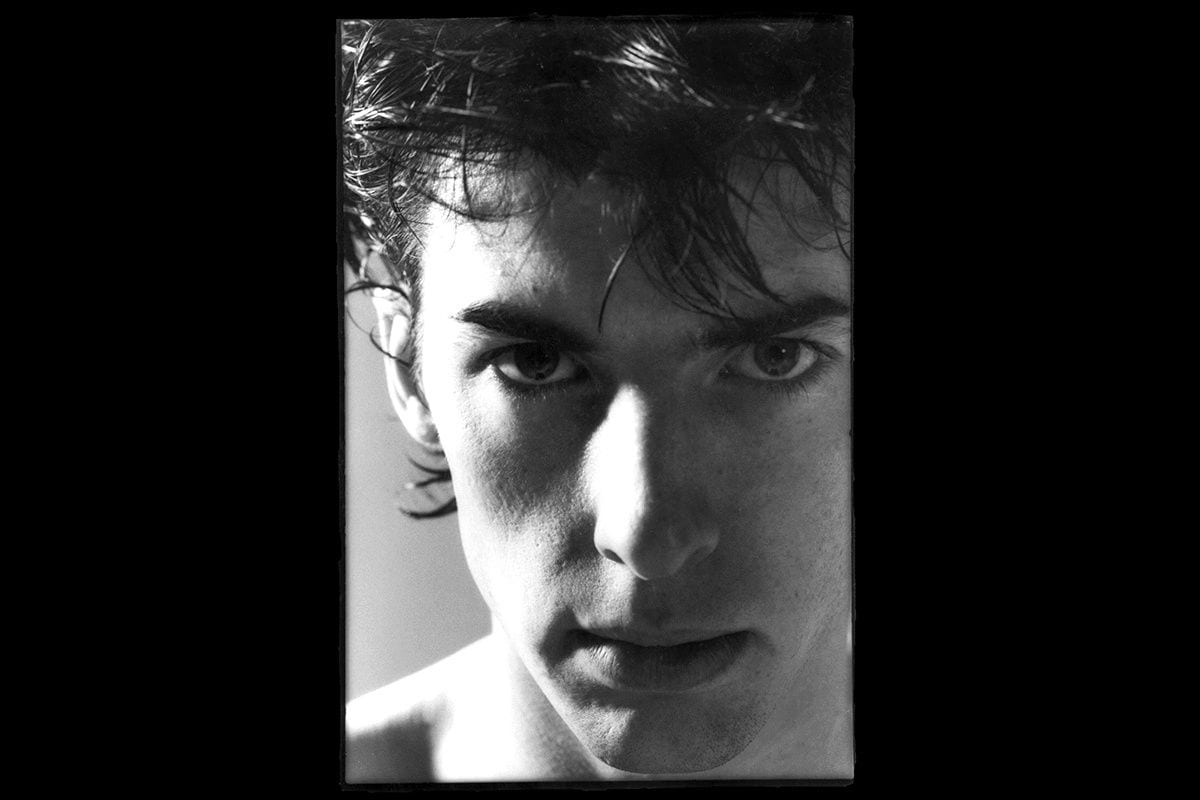

In a Mute retrospective, Miller claims the synthesizer was “the ultimate punk instrument because you didn’t even have to learn those…three chords they told you you needed to play the guitar. I thought it was the next logical step.” Perhaps no one exemplified that idea more than Tovey. Untrained as a musician, he used tape loops synths as a practical measure. He also used furniture, electric appliances, and other “found” objects as necessary. Eventually, he hired a band because he wanted the freedom to move around during his live shows. A performance artist and trained mime, Tovey would dance spasmodically, swing from the rafters, and jump onto bars and into crowds. He got into the habit of covering himself in shaving cream and dropping his severed pubic hair on the audience. Liable to bash drums with his head and bash his head with his microphone, Tovey injured himself regularly, sometimes severely. If he was synthpop, it was only in the most literal sense. Tovey was about as far removed from the fey, carefully coifed, mostly static synth stereotype as Iggy Pop was.

On its face, the music on The Best of Fad Gadget does not mirror the chaotic violence of Tovey’s stage performances. Yet it embodies a certain violence all its own. It’s easy to figure out why Tovey never had a hit; while there is melody, there is not a hint of tenderness. These are deeply misanthropic takes on the messy byproducts of an industrialized, commercialized, nuclear world, with images of carbon monoxide, drunk driving, body dysmorphia, abortion, and the like. When these images are set against sharp, sometimes chirpy synthesizers and drum machines or brassy lounge-jazz arrangements, the effect ranges from subversive to perverse. In Tovey’s world, “stupid magazines spread a social disease”, and a child in the womb is a “love parasite”.

If the synthesizer is a tool of convenience for Tovey, he and his co-producers (Miller and Mute regulars EC Radcliffe and John Fryer) exploit its flexibility in a way that still sounds fresh and exciting. Signature early singles “Back to Nature” and “Ricky’s Hand” are given a primal, visceral power by droning analog blasts and simple electronic percussion. Detail is not overlooked, either. “Back to Nature” starts and ends with a cacophony of electronic simian calls, while “Ricky’s Hand” features a haunting minor-chord instrumental passage with female choral vocals.

Much of The Best of Fad Gadget has a groove and is highly danceable. On the early tracks especially, the overall sound will be familiar to fans of Mute and Miller. To hear the influence on Depeche, all one has to do is compare the hook from “Ricky’s Hand” to Depeche Mode’s “Photographic”. Beyond the surface instrumentation, though, the styles diverge. While most of his contemporaries took pop songs and fit them into synthesized contours, Tovey took punk, noise, and experimentalism and disguised it as pop. His wry, deadpan vocals leave little question as to his roguish intent.

Gradually, as Tovey began working with actual musicians and realized the practical value of striving for a hit in the charts, the pop came more to the forefront. When the music toes the line between pop and absurdity, as on the parlor waltz of “Saturday Night Special” and the swinging jazz of “I Discover Love”, the effect is just as powerful as on the stark electronica. By album number three, Tovey’s music has taken on a bass-heavy, swampy, dance-pop feel that is reminiscent of what Barry Andrews was doing with Shriekback at the time. On some tracks, Tovey fails to find an edge, and the result is undistinguished synthpop which has not aged so well.

As many fearless innovators do, Tovey, who was soft-spoken and sensitive offstage, eventually felt straight-jacketed by the thrilling but reckless persona he had created. Recording under his given name, he spent the late ’80s making protest folk-pop with a Celtic backing band. After a decade out of music, with his clear influence on modern music getting some recognition, he re-embodied Fad Gadget for the Depeche Mode tour, (slightly toned down) stage antics and all. He was working on new music when he died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 2002, only 45 years old.

As The Best of Fad Gadget attests, he left a formidable legacy. Let the celebration begin.