In his video for “Freedom!” (from his sophomore album, 1990’s Listen Without Prejudice Vol 1), George Michael ignited the iconic leather jacket he wore from his breakout solo 1987 hit, “Faith“. It was a symbolic gesture for the pop star—a way for him to relinquish his sex symbol past and to embrace a more mature sound. Listen without Prejudice Vol 1 was supposed to be the record that would make listeners forget his lighter-than-air Wham! past and embrace a more mature substantive sound. Sadly, and although the album was a massive hit, it signaled a noticeable dip in his popularity (at least in the United States; in his native UK, he was still unstoppable).

Even though the hit single “Freedom!” was a smash dance-pop hit, the rest of the album saw Michael slow down the beats and ease up on the synths to refashion himself as a soulful balladeer crooning over tasteful A/C pop. By the time he returned with his third studio LP, Older, in May of 1996, he had deliberately stepped away from his white-hot MTV fame and instead settled on making music that explored deeper and darker tones that owed more to jazz and R&B than his shinier pop past.

Throughout the 1980s, Michael shone brightly—his stunning beauty, coupled with his lilting, feathery soulful tenor, made him the ideal MTV video star. Though he wrote and produced his hits, the kind of respectful critical acclaim that peers like Elton John and Prince enjoyed eluded him. His good looks and his brand of soul-inflected dance music made it easy to underestimate his formidable talent. Faith was a massive success; it sold over 25 million copies and put four singles at the top of the Billboard charts: “Faith”, “Father Figure”, “One More Try”, and “Monkey”. Though he had ambitions of being a “serious” singer-songwriter, a large chunk of his fanbase was teenage girls (an audience that is perpetually dismissed as lightweight and not serious).

His efforts to be taken seriously put him at odds with his label, so he left Sony and signed for the then-fledgling DreamWorks Records, founded by a supergroup of Hollywood heavyweights, David Geffin, Steven Spielberg, and Jeffrey Katzenberg. His first album with them, Older, was a self-conscious but worthy attempt to cement his status as a consequential artist. Like most great artists who came of age during the MTV era, Michael looked to visuals to buttress his message. Gone were the fluffy hair and the dangling earrings, as well as the butt-hugging jeans. The Older George Michael was a sleek panther: his hair close-cropped; his facial hair—that Don Johnson five o’clock shadow— reshaped as a tight goatee; and he was outfitted in sharp, chic, and understated suits and leather blazers.

The album’s first single, “Jesus to a Child”, was Michael’s 14th top 10 US hit. A sad, shuffling ballad, the song is a tribute to Michael’s late lover, Anselmo Feleppa, a man he met in Brazil. Perhaps in tribute to Feleppa’s heritage, the song has a slow Bossa Nova beat without the genre’s expected exuberance. Its tragic inspiration wasn’t made obvious to listeners, and Michael wasn’t out yet. While he played with gender and ideas of masculinity, he never came out, so the song operates as a secret love song whose tortured message of grief and love adroitly kept out any instances of pronouns. Naturally, the video was equally oblique since it showed a gorgeous and fashionable clip directed by Howard Greenhalgh. He lights Michael beautifully and presents a series of arresting images that reference the lyrics.

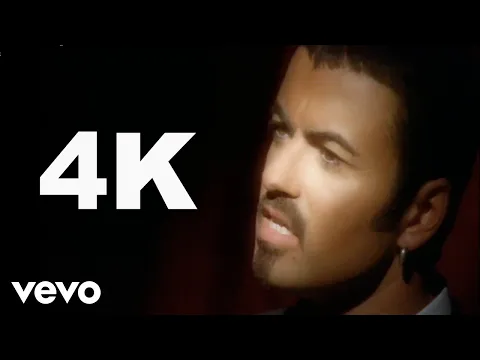

The oblique queerness carries over to the album’s second single, “Fastlove”, his final top 10 hit in the US. Sampling Patrice Rushen’s classic “Forget Me Nots”, the track is an affirmation of both his queerness and his place in queer culture while being simultaneously winky and coy. The lyrics are a celebration of sexuality, and joyous hedonism reminiscent of Sylvester’s “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)”. It’s a funky and bouncy disco song (which only reiterates the song’s gay subtext). The video is vintage George Michael in that it’s a succession of stunning images: sexy dancers and models in various high-fashion-cum-S&M costumes that recall Alexander McQueen. Again, Michael is presented in mood lighting, with half of his handsome visage shrouded in shadow—the makeup artist was a little heavy-handed with the mascara—and he’s separate from the action, not cavorting with any of the models (male or female).

Though he’s purring the lusty lyrics that extol the virtues of recreational sex without commitment, he’s seemingly sexless and isolated, perched on a futuristic chair like a voyeur to the action. He dances in isolation, his body covered in rainwater. Because the video is a time capsule of mid-1990s fashion videography, there are plenty of scenes of near-naked bodies in Eurotrash drag like acid-colored animal prints or neon pleather, and there is a lot of homoeroticism in the video. Still, Michael is sidelined for most of it.

“Fastlove” is the only true dance song on Older and the only real link to his past career as a male pop diva. The closest thing to another dance tune is “The Strangest Thing”, a muted, ponderous house-trip-hop number with Michael’s listless voice floating over the hypnotic beat and a wash of atmospheric synths. (A club remix was later released as a B-side to another dirge-like ballad, “You Have Been Loved“).

Yet, despite these two uptempo moments, the tone of Older matches the album’s fitting title. It’s a self-conscious way for George Michael to shed his frothy pop image and age gracefully. When Older was released in 1996, pop music was a far different place than in the late 1980s/early 1990s, when Michael ruled the pop charts. Grunge was at its apex, and the kind of mainstream colleagues whom Michael could rightly call his peers—Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson, Mariah Carey, etc.—were looking to current pop music trends to remain relevant. The mechanical beats and overachieving showmanship of their earlier work made way for slinkier and funkier sounds. Instead of clattering drums, the songs had swinging beats in which warmer sounds replaced icy cold synths.

Of course, George Michael was working hard to age and mature right alongside them. Older feels extravagant and daring in its willingness to have listeners luxuriate in the thick, pillowy ballads, many of them over six minutes long. Songs like “Spinning the Wheel” and “Move On” explore jazz and cocktail pop influences, whereas “Star People” paid homage to mid-1990s UK soul. Plus, the epic closer, “Free”, is a grande cinematic number, an indulgent symphonic/orchestral experiment that, as an instrumental track, is probably the wittiest way to end a comeback pop record.

Older did many things for (and to) George Michael’s career. It essentially ended his chart success in the States (none of his subsequent albums charged in the Top 10 in America); yet, in the UK, he continued unabated as a hometown hero, with the album becoming one of his biggest successes. UK audiences took to the more contemplative George Michael and made Older a big hit (all of its singles made it to the Top 10 in the UK). More important than its chart positions or record sales, though, is how Older allowed Michael to experiment with his sound and work out his angst (caused, in part, by the death of his partner in conjunction with his inability to come out of the closet). Michael would eventually come out in a rather ignominious way due to being arrested for allegedly engaging in a “lewd act” with an undercover cop at a public toilet in a Los Angeles park; it was a potentially embarrassing episode in his life that he cheekily tweaked in the video of his disco hit, “Outside”.

Older showed an artist who was firmly in the mainstream yet still chafed at being dismissed as merely a “pop star”. It’s an ambitious record that makes a strenuous effort to present George Michael as a cerebral and thoughtful lyricist capable of so much more than what his critics and fans thought. The joyous (and ironic) camp that marked his work with Wham! and his early solo work was set aside to prove that he was talented and able to produce smart, serious music. Was Older ponderous at times? Yes. It’s also pretentious in moments, and the thick, glossy production can feel stultifying and sonically oppressive. Also, it betrays a worry that didn’t need to exist (after all, smart and canny pop ditties like “Faith” are hard to write and shouldn’t be underestimated simply because they’re fun to listen to or because young girls are their primary buyers).

After Older, it looked like Michael was able to strike a firm balance between the two sides of his musical persona: the pop star and the bard. He would go on to embrace dance music again, and more importantly, he embraced his inherent campness. He would never abandon the thoughtfulness of Older—and that’s a good thing because it does feature some of his strongest work.