Ludicrous though it may seem now, there was a notion 30 years ago that Elmore Leonard books didn’t translate to successful movies. At that time, his crime novels of the ’60s and ’70s led to a smattering of forgotten Hollywood Westerns and four grimy, fruitless ’80s thrillers for which he wrote the scripts: Cat Chaser ( Abel Ferrara, 1989), The Rosary Murders (Fred Walton, 1987) Stick ( Burt Reynolds, 1985) and 52 Pick-Up ( John Frankenheimer, 1986). In a traditional Hollywood sense, sure, maybe it wasn’t the most obvious marriage. After all, the author of Three-Ten to Yuma and Other Stories (2006) and Rum Punch (1992) didn’t serialize his universes around consistently recurring characters, nor was his scant, character-driven approach to building settings particularly cinematic.

So when Get Shorty director Barry Sonnenfeld and the late Leonard’s agent said Hollywood wanted little to do with Elmore in 1995 (see the Shout Factory re-release’s bonus features), what they more likely meant was that no one thought of the author as source material for a $30 million movie starring John Travolta, Rene Russo, Gene Hackman, and Danny DeVito.

Now, with neo-classic Leonard adaptations like Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown (1997) and Steven Soderbergh’s Out of Sight (1998) in the rear view, the writer’s legacy as a deep well of genre film inspiration seems a total given. His novels crackle with such voice (and different voices at that) that it can sometimes feel a shame that a movie star isn’t standing there reciting the dialogue out loud to you while you read. These books are violent, stylish capers that don’t ask too much of readers other than to keep up with the brisk pace. The yarns can be incredibly sentimental toward the heroes while withholding all sentiment toward the colorful, but still appealing villains. While Jackie Brown and Out of Sight both loom larger as Leonard-inspired films (mostly due to directors Tarantino and Soderbergh, respectively), no movie has distilled the author’s narrative propulsion and suitably smoothed the “noir” out of noir quite like Get Shorty.

The 1990 novel and 1995 film follow loanshark Chili Palmer (one of the all-time great movie character names, which Leonard plucked from a real-life criminal) from one image-obsessed, palm-studded city to another. Chili departs Miami in pursuit of a debtor and, after a quick detour in Vegas, winds up in Los Angeles. No sooner has he arrived than Palmer pivots from ne’er-do-well chasing to telling everyone he meets he has an idea for a movie. If the industry’s allure wasn’t self-evident to the career criminal, Get Shorty tees up three classic film references in the opening five minutes alone — our gangster likes Cagney, Pacino and The Thin Man.

But those are just the unimpeachable influences to Chili’s love of film; contemporary Hollywood, by contrast, is often set up just to be knocked down. It’s full of exhausted, exploited actresses like Karen Flores (Rene Russo), hack producers like Harry Zimm (Gene Hackman) financing schlock with drug money, and pompous stars like Martin Weir (Danny DeVito), who shamelessly bait Oscar every year. (“Is that the one about the crippled gay guy who climbs Mt. Whitney?” Palmer asks, trying to remember one of Weir’s fictitious roles.)

While Get Shorty has routinely been characterized as Leonard’s “revenge” on Hollywood for not embracing his work, it also appeals pretty heavily to the industry’s eternal promise of reinvention and for standing out if you’ve got the goods. Barry Sonnenfeld certainly doesn’t make LA look like a superficial hellhole. He foregrounds style, camera mobility, and a swagger solidified instantly by John Lurie’s jazzy score of cyclical sunshine bop. That swagger is, in fact, so evident that John Travolta simply walking toward things in the film becomes a set piece. And in those catwalk-like saunters, which Sonnenfeld captures with extended dolly shots, the director celebrates an essential quality of Elmore Leonard’s writing, too — it moves, no matter what. (How else are you going to write a novel every year for 40 years?)

So goes the plot of Get Shorty. Palmer leapfrogs from his initial assignment into collecting a different kind of debt from producer Harry Zimm. While breaking into Zimm’s house to confront him, he meets Karen, for whom he eventually falls. Through Harry, he meets drug smuggler Bo Catlett (Delroy Lindo) and his henchman Bear (James Gandolfini), who want a piece of the new movie Zimm is pitching to movie star Martin Weir. That script is quickly tabled by Weir in favor Chili Palmer trying to peddle his own story, one about a noble Miami “shylock” who finds himself on a wild goose chase in Los Angeles. This chaotic character web is typical of many darker, more revered crime novels (pick any Raymond Chandler you like), but it’s treated as completely uncomplicated by Leonard and Sonnenfeld as they connect characters, and soon there’s nothing left to do but crisply resolve the plot.

That accessible approach to filmmaking and writing gives Get Shorty its still-ample sizzle — that and the Leonard one-liners that screenwriter Scott Frank says (in the Bluray bonus features) often made his job quite easy. All Frank had to do with many standout bits of dialogue was leave them in. “I’ve seen better film on teeth” is a particular winner that Bo Catlett spits at Harry Zimm at one point. Delivering a patented Leonard jab ought to be a career ambition for any character actor, but Get Shorty also fields several performers who excel at absorbing them.

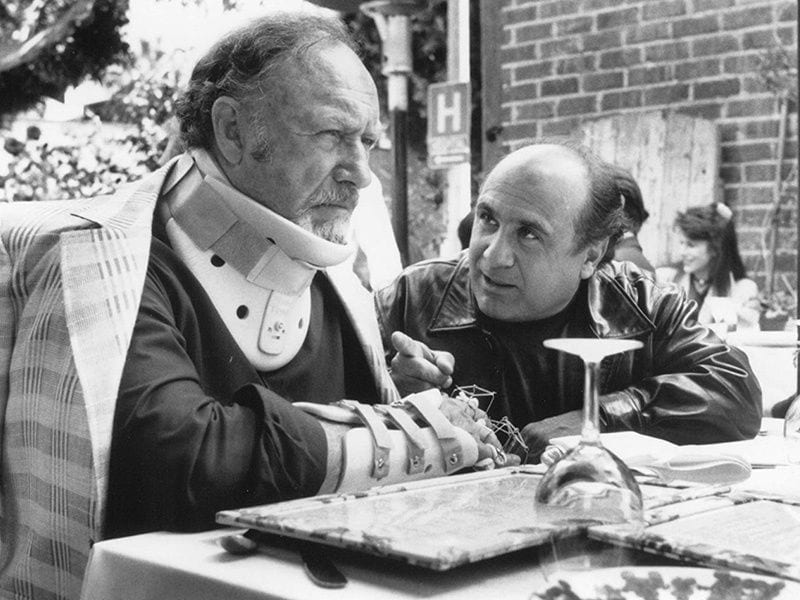

All due respect to Russo, Lindo, and Dennis Farina having a ball here, it’s Gene Hackman’s singular performance that elevates Get Shorty above a vast pile of post-Pulp Fiction Travolta vehicles. Hackman is up to something he arguably never did before or since: playing an outright loser in Harry Zimm. He fashions himself a Roger Corman acolyte but is weighed down by gambling debts, loneliness, and a genuine lack of taste in movies. Here, the same Gene Hackman grin moviegoers have come to associate with knowing malevolence from Little Bill Daggett (Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood, 1992) or Popeye Doyle (The French Connection, William Friedkin, 1971) creases upward just ten percent more to appear sheepish and put-on. Even more remarkable is a body language transformation from Hackman. He lets his barrel chest sink in and flails his hands constantly, making a usually indomitable screen presence appear, in one scene, to be the smallest person at a table that includes Danny DeVito.

Through hacks like Harry Zimm and Martin Weir, Get Shorty characterizes Hollywood as shallow, but the film houses some deeper, even confounding contradictions if you look. One particularly brain-scrambling motif is supporting characters’ obsession with Chili Palmer as a new and authentic presence in town, cutting through the Los Angeles veneer with his masculine directness. “Look at me” is the refrain Palmer lays on lesser man after lesser man, an invitation to cut the bull, lock eyes, and see who’s more real. DeVito’s and Hackman’s characters each fall for this trap, only to steal and reemploy it themselves later in the film.

But of course, there’s nothing authentic about Travolta’s gangster schtick at all. He’s John Travolta, not Chazz Palminteri. And it takes only a few behind-the-scenes clips to discover he’s the highest maintenance and least comfortable actor on set. What Get Shorty is appealing to, then, isn’t naturalism; it’s star power. It takes potshots at the authentically inauthentic (great characters playing clowns) while celebrating the inauthentically authentic (pampered stars playing preternaturally cool wiseguys). In this way, Get Shorty belongs to a long line of spoofs that still appeal to Hollywood magic in their very design.

While it’d be difficult to mistake Elmore Leonard for any of his roguish protagonists, his and Chili Palmer’s journeys in this instance are parallel. Whether a world-weary mob enforcer or workmanlike novelist jaded with how his previous scripts were received, the outsider gets to covet the admiration of a world he looks down on at the same time. If that’s revenge, then it’s a joyous delusion.