In The Queer Art of Failure, Judith (J. Jack) Halberstam posits that failure is a type of freedom and therefore a mode of success. Gracie Allen in many ways anticipates the modes of “success” that Halberstam applies to comic cartoon characters like Dory from Finding Nemo. Indeed comedienne Gracie Allen cut a similar figure in the first half of the 20th century. Her linguistic and social failures allowed her, for a time, to complicate and combat the expectations of the 1940 presidential campaign.

Allen’s career spanned nearly 40 years, moving from vaudeville, to film, then radio, and ultimately television. Although she’s probably best known to modern audiences for her work on the television program The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show (1950-1958) (Also called Burns and Allen, Allen and her partner George Burns became radio regulars in the ’30s with frequent guest appearances and two eponymous radio shows. Allen was the funny man to Burns’ straight man. Their relationship and marriage provided the keystone of the situation in the situation comedy across media. One might expect to see traditional patriarchal gestures in these shows, but Allen circumvents Burns’ authority through overly literal understandings of language. Allen’s performative resistance to societal expectations liberates her.

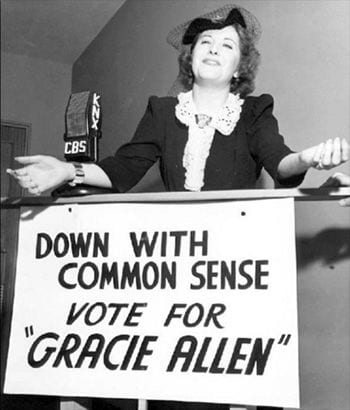

Allen’s true genius, however, lay in her public performative failures. One of her most notable failures happened in 1940 when Allen ran for the office of the US President as the candidate for the political party of her own creation, The Surprise Party. The origins of the campaign are unclear. One story says that the campaign emerged from a writer’s conference for the radio show. Another more playful story has Allen confess to Burns that she wants to run for president as she knits at home. What had begun as an idea for a bit ballooned into a multi-episode story arc, multiple crossovers to other radio programs, a book, a campaign tour, and a national convention. Mrs. Roosevelt even invited Allen to the National Woman’s Press Club as the guest of honor (Carroll 7, 11).

Throughout the campaign, Allen uses her femininity to challenge and wedge herself into male politics. In her 1940 book How to Become President, she gives her sassy explanation that Franklin D. Roosevelt should happily give his seat in office to a woman since he had already held it for eight years. Some of her platforms pushed gender concerns to the surface. One campaign plank states that “A chicken in every pot is good, unless you are the chicken.” However, Allen goes on to suggest that a better goal would have been “a girl for every knee”.

With these slogans we see how women are reduced to consumable goods. This rhetorical move suggests that political promises hide something predatory, even when seemingly benevolent. Yet feminine vulnerability can be used as a tool to mitigate male power since this is one of many instances where Allen sexualizes herself to assert her political acumen.

Along these lines, Allen’s stump speech included the line, “Everyone knows a woman is better than a man when it comes to introducing Bills into the House.” She plays with gender stereotypes equating masculine political deftness with feminine fiscal apathy. It’s a gesture she reinforces with the frequent punchline that the Americans should be proud of the the national deficit because it is the largest in the world.

Ultimately, these moves reveal that Allen’s national public performance of failure was “queer” in the sense that it was a conscious conflation of gender expectations. By permitting herself the linguistic ambiguity that she lampoons in others, Allen opens a space in which she seems to acknowledge the constricted political power of women while asserting the ultimate impotence of masculine power structures. Combining both what Halberstam calls “naturalize[d] female stupidity” (55), alongside the audaciousness of a female candidate, Allen exists in this seemingly contradictory mode.

The critical contradictions of Allen’s campaign are expressed in the Surprise Party slogan, “It’s in the bag”, which carries dual interpretations. “In the bag” being a slang expression that means both “a sure thing” and also “drunk”. Indeed, it’s this recurring conflation, this queering of meaning, where Allen most succeeds at failure.

In the 28 February 1940 episode of Burns and Allen, “Government Jobs”, Gracie Allen first challenges our sense of what can lead to power and the crucial structures that manifest the full implications of its execution. In her silliness there’s an underlying ideal that power is naked. She assumes the authority of the presidency without ever assuming the office by offering her friends cabinet positions.

Burns, frustrated that Allen’s political ambitions are impeding the radio show, contacts the sponsor, the A. S. Hinds Company. Burns intends on absolving himself of what he considers a debacle. Burns’ frustration at the silliness backfires. The company’s president supports Allen’s candidacy because he has been offered the position of Secretary of State.

The 29 May 1940 episode of the radio program “Sweeping Into Office” demonstrates how linguistic and logical failure can lead to political gain. The program broadcasts from San Francisco, Gracie’s hometown. Allen understands that power is a game that does not demand culpability. The trick of power is that it absolves those who possess it. A small way in which her humor illustrates this is when she campaigns in her hometown. She receives a call from her sister that she has left the brake of her car off and that it is careening down the street:

Burns: What happened?

Allen: I left my car parked at the top of Lombard Street Hill, and I forgot to put the breaks on. It’s the funniest thing. The car is running down the hill.

Burns: What’s funny about that? Somebody might get killed!

Allen: Oh, that’s impossible. There’s nobody in the car.

Burns: What about the pedestrians?

Allen: The car is moving so fast they won’t have time to get in!

She laughs as Burns frets that someone might be hurt. In her view no one could be hurt because no one is driving. The driver is the key to the situation. Everyone else is of no consequence. This scenario echoes her frequent punch line that she “would rather be President than right. .Ultimately, power is its own justification.

Allen’s silliness and dizziness complicate the implications of her campaign. Halberstam’s description of Dory from Finding Nemo could easily be applied to Gracie Allen. They write, “By some standards she might be read as stupid or unknowing, foolish or silly, but ultimately her silliness leads her to new and different forms of relation and action” (54). Allen’s stupidity and dizziness create a novel form of relation at the end of the episode “Sweeping into Office”. The conclusion of the episode reveals Allen’s learning process, which is described as being clever but backwards.

The main narrative of this episode involves Burns trying to court the politically influential J. J. Clifford for the Surprise Party while Allen entertains people from her past. Allen’s encounters are zany and lighthearted. Always she asks about Stinky, the boy with buckteeth who chewed “I love you” into her desk. But no one is sure what has happened to this boy.

This episode also features the culmination of a series of interrelated bits about beards. The dumb humor and illogical nature of these bits can make them difficult to understand. Yet the line of flight does reveal Allen’s unwise wisdom and foggy acuity.

The bits begin with the Surprise Party decision to have all the male delegates grow beards before the convention. These bits transition into a series of puns such as “Keep America fuzz”. The title of the episode is a beard pun itself since “Sweeping Into Office” refers to the way the beards of Allen’s supporters resemble brooms. The nadir of these jokes occurs at the Omaha Convention at which Allen and her compatriots play a game called Beaver. Allen describes the game to Burns like this:

Burns: Gracie, aren’t you thrilled? Everyone here in costume. Thousands of men wearing beards.

Allen: Oh yes, it’s a hair-raising experience. But I’m always hollerin’ “Beaver!” Oh, there’s one! “Beaver!”

Burns: Beaver? What’s that?

Allen: It’s a game everybody plays. If you see a man with a beard and holler “Beaver!” it’s five points. And if you see a man with a moustache, it’s onlI three points.

Burns: Well, what would you get for a face like mine?

Allen: A mask.

A Contentious Political Landscape

Returning to the narrative of “Sweeping Into Office”, Burns tells Allen that Clifford will be stopping by the broadcast, but due to his shyness they should not make fun of his red beard. The man’s vulnerability is too great a temptation for Allen and her friends. When Clifford arrives, they play their game repeatedly calling him “beaver”. After a confrontation between Clifford and the regular ensemble, the show ends with the revelation that Clifford was the boy with buckteeth who chewed wood. The multiple-episode line of flight between men with beards, the children’s game “beaver”. and the search for the boy who looked like a beaver ends with a warm embrace. It illustrates Halberstam’s assertion “the absence of memory or the absence of wisdom — leads to a new form of knowing” (54).

Throughout the campaign, Allen simulated the accumulation of power through her very public performance of failure. America laughs at Allen’s gendered stupidity that she demonstrated through what is clearly an intentional reliance on literalness and linguistic ambiguity. Halberstam writes, “Stupidity in women, as we know, is often expected in this male-dominated culture, and some women cultivate it because they see it rewarded in popular icons… Stupid women make men feel smarter” (57).

However, Allen commandeered the mechanism of female stupidity as a way to undercut the real implications of masculine power. It’s little wonder that somewhere during the campaign, the public began to seriously embrace Allen’s farce by listening to the radio show, ordering the sheet music for her campaign song, attending her campaign events along the whistle stop tour, and nominating her at the Surprise Party Convention in Omaha, Nebraska.

The year 1940 was transitional for Americans, even if they weren’t aware of it: it was the tail end of The Great Depression, and just before the United States entered WWII. Allen was mounting a campaign in a contentious political landscape. Numerous Republican candidates were competing for the official party nomination. Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, was vying for a third term despite public anxiety that financial prosperity would not return.

Allen captures the anxiety surrounding these concerns by giving prosperity the following definition: “Prosperity is when business is good enough so you can buy the things on credit that you can’t afford anyway and that way you can save enough money to pay cash for new things after they have taken back the things you bought on credit.”

Americans were exhausted by the preceding decade-long Depression and Allen offered an honest and light-hearted assessment of both the political and domestic situation. In one verse of her campaign song, Allen captures the American fear and anxiety of helplessness in the face of the current financial situation:

Even big politicians

don’t know what to do.

Gracie doesn’t know either,

But neither do you.

Since the President, congress, senate, and voters themselves do not have the answers to repair what was commonly perceived as a broken America, Allen now becomes an equally viable option in opposition to the impotent patriarchal political structure. Allen’s political cartoons and campaign song revealed what many Americans were already thinking.

It’s here that Allen’s gendered performance of failure begins to actually fail. The frenzy surrounding her candidacy on her weekly radio show led to guest spots on other popular shows of the time, Jack Benny and Fibber McGee and Molly. She even received Harvard’s student-body endorsement. Allen traveled across the country in a parody of the traditional campaign train, stopping at small towns across the West and Midwest, culminating with her arrival at Union Station in Omaha, where she was met at the train station by more than 4,000 supporters (Carroll 87). It’s estimated that more than 100,000 people turned out to hear her speak (Contenders), 75,000 of whom were in Omaha alone (Carroll 105).

What had started as parody was rapidly becoming authentic. Allen’s inevitable public failure as the dark horse candidate began to gain power it its own right. Of course, it’s not that anyone thought Allen would actually become president, but with literally thousands of people at each of her whistle stops, Allen was suddenly in the position of swaying the outcome of the “authentic” election.

She announced her “withdrawal” from the campaign shortly before the 4th of July. She tried to assert the importance of electing a real politician by saying, “This is a presidential year and we are on the eve of selecting a President in the gravest period of our history. Every American should consider casting his 1940 presidential vote the greatest privilege of his life” (qtd. in Sloane). Yet Allen queers the meaning of authentic political power by unintentionally failing at her intentional failure. Even though she recedes from a race that she was never actually running, she still received several thousand write-in votes during the presidential election (Carroll 14).

One of her detractors, columnist Wood Sloane argued that the American acceptance of Allen’s sham campaign was due “to our National tolerance of stupidity”. But perhaps some of those exhausted voters who toed the Surprise Party line understood Allen to be a Shakespearean fool (albeit in a sexy evening dress) revealing the foibles of power.