Creating the Perfect Scapegoat

The Titans are not your average monstrosities. Isayama took great care in creating them, and the peculiarities of their design are neither to be understood as trivial, nor as being primarily for the purpose of shock-value, even if their arresting appearance has provoked within readers a morbid fascination that is believed by some to have heavily contributed to the series’ rise in popularity.

When they first break through the wall, the Titans appear to Eren—and therefore to us—as the incarnations of absolute evil. Incapable of speech or rational thought, they pursue human beings—which are, by the way, the only organisms in which they express any interest whatsoever—much like animal predators pursue their natural prey, but with much greater fervor and vitality. Unlike animals, however, Titans do not devour human beings for nourishment. Practically immortal and able to regenerate lost limbs—including heads—almost instantly, they seem to be in it solely for the kill. This notion is supported by the fact that many of them sport a frozen, menacing smile. Last but not least, they lack reproductive organs, leaving it unknown—at least at the beginning of the story—how they progenate.

The Titans can be seen as a kind of exaggerated version of how people, willingly and unwillingly, visualize the enemy: ethically amoral, physically grotesque, and uncanny in their resemblance to ourselves; human in some ways, bestial in others. Mindlessness, malevolence, indestructability, and infertility—these four characteristics resurface, rather prominently, in the writings of both academics and demagogues, regardless of whether they are left or right-wing. One of fascism’s most vocal critics, Winston Churchill, adamantly maintained that totalitarian states thrived on the control of information, and survived only for as long as they prohibited their subjects to think for themselves. During an address delivered to the US Congress in 1938, he argued that what such regimes feared most was not the military might of foreign powers, but the “words and thoughts” of their own people.

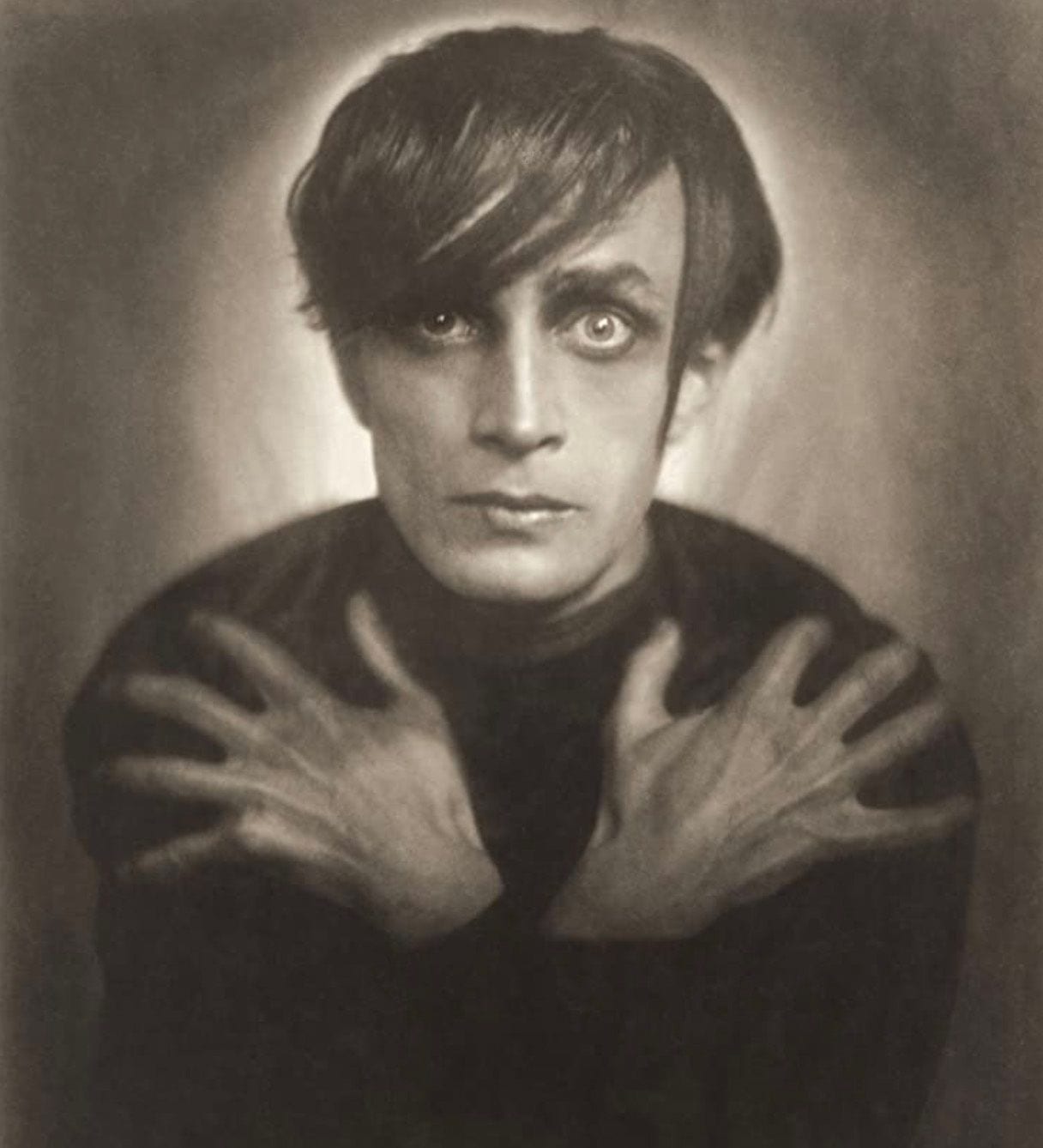

To find historical evidence supporting the prime minister’s claims, one need only turn to the Reich’s Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, which bestowed upon Nazi bureaucrat Joseph Goebbels virtually unlimited authority over the production of art and journalism, thus ensuring that not a single sentence, whether uttered on the stage or printed in a newspaper, contradicted the beliefs of the Führer. Nor was Churchill alone in denouncing the Third Reich as a system based primarily on anti-intellectual coercion. Arguably one of the most memorable representations of the prototypical Nazi soldier and Reich citizen appeared in the 1921 classic film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari under the name Cesare, a mute and mindless slave who—much like Isayama’s Titans—had neither the freedom nor the mental capacity to question the murders his autocratic master forced him to commit.

Conrad Veidt in Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920) (Photo by Imagno/Getty Images / IMDB)

Although the Titans’ lack of reproductive organs can be attributed, rather straightforwardly, to a matter of censorship, it would be unwise to rule out the possibility that this anatomical subtraction was, at least to some extent, a conscious decision on the part of Isayama. German socialist Klaus Theweleit, in a recent study on the fascist imagination called Male Fantasies, discusses at length the conception of the enemy as an impotent creature, one whose inability to give life forces him to take the lives of others instead. Krafft, the masculine hero of Hans Zöberlin’s 1937 novel The Command of Conscience (Der Befehl des Gewissens), narrowly avoids a death trap in the shape of an infertile yet libidinous Jewish woman longing to drag the honorable Aryan into the “emptiness, night, and moral solitude” of her existence.

Antisemitism aside, fear of sex and, consequently, sexual desire was by no means unique to Nazi thought, but rather a widely shared sentiment around the globe. Both world wars witnessed whirlwinds of mass-produced and distributed illustrations designed to combat the spread of venereal diseases, with one example of the American persuasion warning soldiers against “booby traps” they may encounter abroad, and another, bent on communication the same message, showing two naked people as their intercourse is interrupted (or prevented) when the female partner’s head suddenly transforms into a terrifying, snakelike creature, one whose elongated throat lined with rows of breasts.

The understanding of unrestricted desire as both a self and race-destroying enterprise led the Third Reich to reverse many of the steps taken towards sexual liberation by the Weimer government. It did so, for instance, by the banning and burning of books from sexologists and activists like Magnus Hirschfield and Max Marcuse, as well as by instituting the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which prohibited mixed marriages and extramarital relations with people of inferior race.

Like Zöberlin’s female siren, the male beast became an equally dreaded manifestation of the sex-deprived degenerate. Fear of the “rapacious bestial Jewish male” looking to force himself onto and thus defile “innocent German femininity” grew widespread, thanks to provocative posters showing, among other propagandist scenes, Jewish octopuses latching onto a chaste incarnation of the Aryan motherland—an image which becomes even more striking when considering that Isayama’s Titans possess an exclusively male physique, while the three walls that protect Eren’s society are personified by and named after three female goddesses: Maria, Rose, and Sina.

- Attack on Titan 1 (9781612620244): Hajime Isayama ... - Amazon.com

- Attack on Titan: Colossal Edition 1 (0884937702974 ... - Amazon.com

- Hajime Isayama

- Hajime Isayama - IMDb

- Hajime Isayama (@hajime_isayama) | Twitter

- Hajime Isayama | Attack on Titan Wiki | Fandom

- Watch Hajime Isayama draw Levi from Attack on Titan (2017 ...

- 14 Things To Know About Attack on Titan Creator Hajime Isayama ...

- Manga artist Hajime Isayama reveals his inspiration - BBC News ...

- Hajime Isayama - Wikipedia

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)