While still on his way to becoming one of the most popular heroes in movies, Douglas Fairbanks starred in films for Triangle Film Corporation during 1915-16. This Blu-ray from Kino Lorber offers restorations of two such titles showcasing his athletic he-man charm. The Half-Breed belongs to a western subgenre, not uncommon in the Teens, of “Indian romances” sympathetic to Native American characters. The title cards, scripted by Anita Loos (Gentlemen Prefer Blondes) from Bret Harte‘s story “In the Carquinez Woods”, lean heavily on sarcasm about “the superior white man” while showing scowling riff-raff and drunkards who make our noble hero’s life a trial.

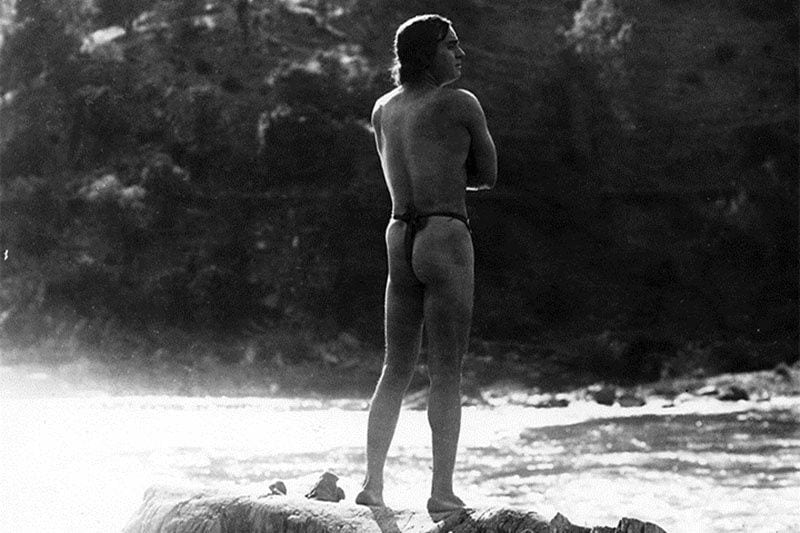

A prologue shows his mother, “betrayed by a white man” and shunned by her own people, leaving the babe with an elderly white man in a mountain cabin before leaping picturesquely to her death. She wanted him to be raised as white, but the kindly man brings up Lo Dormante (derived from French for “Sleeping Water”) to be conscious of his heritage, which also means the locals never let him forget it and keep reminding him not to act like he’s as good as “his betters”. The buckskin-clad lad prefers the company of the forest, where he makes a living filling mail-order requests for plants and herbs, making a home inside a giant hollow sequoia, and taking dips in the lake while wearing a skimpy loincloth.

Among the many characters are two women who form complex romantic triangles. Jewel Carmen plays the ambitious daughter of a hypocritical preacher (Frank Brownlee), while Alma Rubens plays Teresa, apparently a Mexican who hides in the forest after stabbing a couple of guys. Both women think Lo’s kind of cute, and both are criticized by white men for lowering their standards. Those white men include the sheriff (Sam De Grasse) who’s actually Lo’s father, though nobody realizes it.

Robert Byrne restored this film in 2013 from three wildly varying prints made at different points in its release history, sometimes with extensive re-editing. He provides a thorough discussion and examples in an extra, and he joins Fairbanks biographer Tracey Goessel on an informative commentary track. They’re both fascinated by the social elements, which are often more progressive and frank than would be common in ensuing decades.

For example, it’s clear that the bargirls are prostitutes, and sexual innocence is in short supply among the characters. Byrne also remarks that he’s never seen such an integrated bar sequence, with Chinese and African-American characters playing poker nonchalantly with white men. That sequence also features Lo discouraging three drunken Indians from dancing for the white men’s pleasure, and being called a killjoy for his troubles. Goessel states that throughout his career, Fairbanks scrubbed his scripts of racist elements. This is a rare example when racism is foregrounded as a theme, and some later versions removed it entirely by simply labeling his character a mountain man.

This movie’s aesthetics are equally fascinating. The production was supervised by D.W. Griffith, one of Triangle’s three founders (with Thomas Ince and Mack Sennett), but the decisive visual artists were director Allan Dwan and photographer Victor Fleming, the future director of Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz. The commentators can hardly stop ooh-ing and ahh-ing at the beautifully composed moments of backlighting and Rembrandt-esque chiaroscuro among the giant trees at Sequoia National Park, where it was filmed.

There are only a few examples of Fairbanks’ patented smiling athletics, as he mostly stands around morosely with arms folded while the other characters drive the plot. He does leap gracefully over a high fence in an aw-shucks manner, and at one point he uses a tree as a kind of pole vault in a reversed trick shot. The general lack of athletics may have been why the film flopped, despite glowing reviews. Audiences were more receptive to the bonus film included on this disc, the same year’s The Good Bad Man, also directed by Dwan and shot by Fleming and featuring some of the same supporting cast.

As big as all outdoors, with very striking high-angle shots contrasting foreground figures against tiny distant figures on the desert floor, this western again finds Fairbanks’ hero worried about his seemingly illegitimate birth. He becomes an oddball outlaw who provides for orphans “born in shame”. Eventually, a complicated backstory is revealed, leading to the thirst for revenge against the ornery polecat (Sam De Grasse again) who plugged his pappy.

The romantic interest is provided by a teenage Bessie Love, early in a long film career and already in command of a fetching naturalism. Fairbanks himself wrote the story, and Goessel reveals intriguing details about his own illegitimacy and his problematic relations with his father and stepfather. It may be going too far to read a wish-fulfillment into this scenario, or perhaps not.

Neither film is tinted. Both look mostly very fine, sometimes ravishing, with obvious differences between the prints used in the first film. Both have excellent, nuanced scores by Donald Sosin. We are left to hope that more Dwan and Fairbanks items are on the way. Indeed, we’d jump for it.