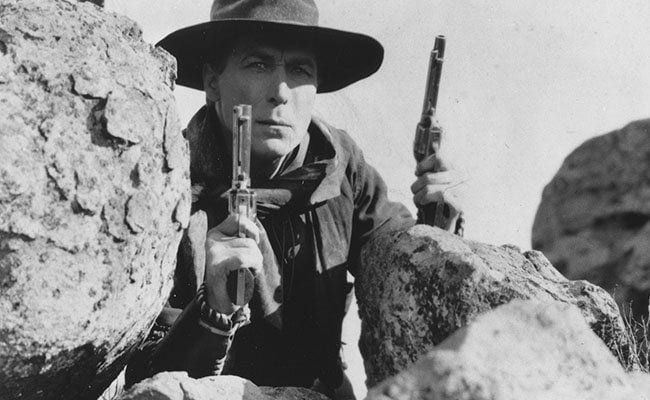

Rugged, weatherbeaten, conventionally unhandsome, even funny-looking enough to play his own comic sidekick to his own manly hero, William S. Hart was justifiably the most famous western star of the silent era. Now on Blu-ray as a welcome surprise is Wagon Tracks, one of at least half a dozen features he made in 1919 and among his most popular epics, in a tinted Library of Congress print in beautiful shape.

The visual style is entirely modern, with the action cutting between concurrent scenes in different locations and lots of close-ups to showcase Hart’s camera-ready command of expression, always vivid and direct without overplaying. Hart’s paradox is that although he’s a very expressive actor, it’s at the service of his character’s essentially taciturn, isolated image of “true manhood”.

Director Lambert Hillyer and the great cinematographer Joseph H. August balance the close shots with strikingly picturesque vistas of humans dwarfed by the vast desert, graceful images of a paddle-wheel riverboat on the shimmering water, carefully shadowed night scenes, and geometric arrangements of wagon trains on the Santa Fe Trail.

C. Gardner Sullivan’s story is simple yet cleverly constructed. As noted trail leader Buckskin Hamilton (Hart) sallies east toward the Missouri River where his young doctor brother is arriving by steamboat, the film cuts back and forth between the cheerful Hamilton chatting and bedding down with his horses while the brother (Leo Pierson) gets himself shot after confronting a card-sharping polecat (Robert McKim). The polecat’s pretty sister (Jane Novak) is tricked into believing she accidentally shot the man herself while defending her brother. The deceit is abetted by the polecat’s friend (future director Lloyd Bacon).

The scene of Hamilton’s discovery of his brother’s body and his discussion with the other characters shows how Hart was a type of screen hero soon to disappear from westerns, which would be full of action heroes typified by Tom Mix. Hart belongs to an earlier school of melodrama, and he’s not afraid to show his character breaking down and weeping — in a manly way, of course — before jutting up his hawk-nose and casting his watery eyes to heaven for strength. It’s effective, and we can’t imagine John Wayne doing this. He’s balanced in the complexly emotional scene by the equal mournful heroine, whom Hamilton thinks too lovely to be guilty, and the frowning squints of the polecats.

The party joins Hamilton’s wagon train on the Santa Fe Trail, where the artistically painted title cards are forever extolling the destiny and determination of the “unconquerable race” in an unabashed celebration of western mythology. The wagon train meets some Kiowa Indians, “insolent but inclined to be friendly”, one of whom gets impulsively shot to death by a settler who misinterprets the Indian’s actions; it’s a telling detail. The Indians issue an ultimatum: a life for a life, or they’ll attack at dawn after spending all night in a traditional feathered war dance around their fire. While this has been going on, Hamilton has been off on a separate grueling plotline with the polecats, and it will all wind up together.

At under 70 minutes, it’s a brisk and well-made feature with many moments of beauty in its sustained atmosphere of emotional tension and historical grandeur, and one of many perfect vehicles for the overwhelmingly popular Hart. Although the director is Hillyer, who spent most of his prolific career in B westerns well into the talking era, the primary auteurs are Hart himself and producer Thomas H. Ince, who collaborated on many similarly handsome western melodramas.