Most revolutions are difficult, messy, hard to easily summarize and perhaps impossible to clearly be reflected in a narrative. Add the complications and implications of race and a clearly subjective art form like comedy and the end result can sometimes be overwhelming. Compress the perspective from roughly the late ’60s through the mid-’90s and the story will always seem unfinished. The alpha and omega of black comedy was definitively set in stone with Mel Watkins’ 1994 On the Real Side: A History of African American Comedy from Slavery to Chris Rock (Chicago Review Press, 2nd ed. 1999); the book is clear, objective, and deeply profound about the ways a marginalized people rose up from within institutionalized racism to present themselves in the comic realm. It’s a tome worth reading, a volume that earned its weight (literally and figuratively) and is a fitting document to the 20th century. Where would black comedy go in the 21st century? What patterns could we expect to re-occur, in different variations, to give voice to this particular experience?

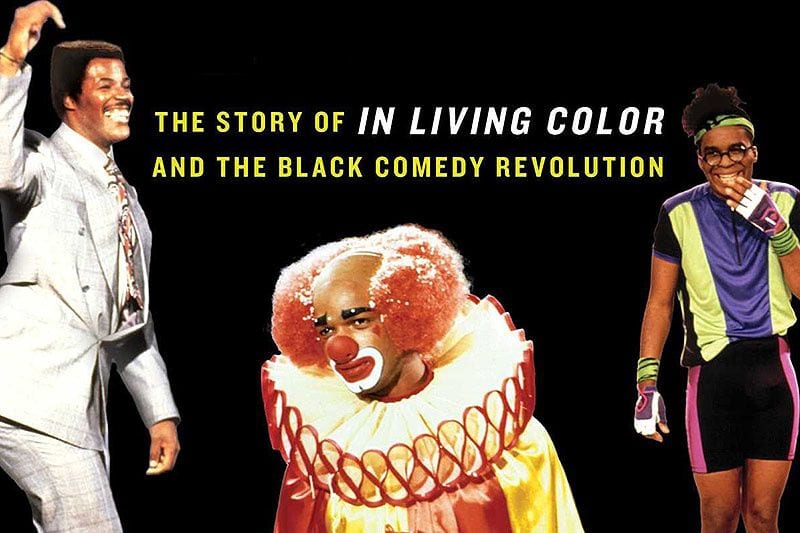

David Peisner’s Homey Don’t Play That: The story of In Living Color and the Black Comedy Revolution has the distinct advantage of time over the Watkins book, but the approach is decidedly different. On The Real Side was published the year In Living Color went off the air. By 1994, as Peisner notes, the landscape for black comedy was decidedly different than the late ’80s. Shows like Martin, arguably a child of In Living Color creator Keenan Ivory Wayan’s sensibility, was still going strong, and the landmark apparent respectability of The Cosby Show and its lead character Dr. Cliff Huxtable (Bill Cosby) was gone. Will Smith’s The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air would last until 1996, and other such shows lingered through the decade with various degrees of success.

What does this all mean to the premise that In Living Color revolutionized black comedy? Deeper than that, Peisner argues (with some success) that the initial success of the show meant something. He opens with a picture of Wayans, accepting an Emmy for the show in its freshman year:

There had been important breakthroughs… but the march of progress was… slow… [u]ntil suddenly it wasn’t. Not only were there Eddie [Murphy] and Arsenio [Hall] and Robert [Townshend] and Keenan, but there were Spike Lee and Oprah Winfrey… In Living Color [was] a black show created by a black man that seemed to effortlessly cross over to a mainstream audience ready and waiting for it…

Peisner ends his Preface by noting that this was the first and only Emmy the show would win, in spite of 15 additional nominations over the next four seasons. This show that gave a nascent home to such talents as Jim Carrey, Jamie Foxx, David Alan Grier, Tommy Davidson, and all of the Wayans (Keenan, Kim, Damon, Marlon, Shawn) burst like a magnificent firecracker in the first four years of the ’90s and, like that firecracker, quickly disappeared. In the shadow of such real-life events as the 1992 L.A. Riots following the acquittal of four white police officers in the beating of black motorist Rodney King, In Living Color was never overtly political, but it gave voice to those who had been marginalized. It was reviled by many in and outside of the community, but its shameless and unapologetic energy was part of its charm

The problem with charm and bravery within the context of a particular time is that it doesn’t have a long shelf life. In Living Color was a sketch show aimed at a black audience and one of the centerpieces of the Fox TV network in its early days. Peisner is probably generous to a fault in his conclusions about the legacy of the show:

Those big, loud, hard laughs came not just from being smart or clever or witty or black but from being outrageous… This was a show willing to upset people in search of those big, loud, hard laughs. They said the un-sayable. That’s a legacy that always needs periodic renewing…

The problem with such pronouncements (and Peisner circles around these themes more times than necessary) is that he can’t seem to admit that the particular sketches of In Living Color really don’t hold up. Granted, comedy is a cruelly subjective art form, and not much of it survives outside of its time frame, but the pieces are very thin. Peisner does admit that such skits as “Homey the Clown”, “Men on Film”, and “Fire Marshall Bill” are probably anachronistic in 2018, and the end result is a book that relies too much on extensive author interviews with cast members, producers, and various scene makers at the time. Perhaps in that sense Peisner understands his material, but it can be frustrating for a reader who may not be as familiar with these landmark TV skits. Certainly they were audacious in their time, but sometimes what’s delightfully bitter in the early ’90s just becomes unsatisfying with age.

Homey Don’t Play That wants to work on several levels, and the reader risks whiplash following the trains of thought. An unexplored narrative strain Peisner develops early on is the Wayans family childhood, life in the Fulton Houses for the nine Wayans siblings in the mid-60s through the mid-’70s. The story of the matriarch, Elvira, is worth a separate volume. Peisner incorporates understood facts about the status of Flip Wilson at the time as a black comic on TV, the transformation of Richard Pryor from a man who wore a suit and tie to a man who challenged the establishment by speaking about truth and black power. Keenan leaves for a while to study at the prestigious Tuskegee Institute and he comes home to a New York City in the late ’70s/early ’80s brimming with comic possibilities.

Again, Homey Don’t Play That benefits more from the power of its surrounding stories and subplots than the strength of benchmark In Living Color recurring characters like Jim Carrey’s female weightlifter character Vera DeMilo and Jamie Foxx’s Ugly Woman Wanda. The story of how NBC’s The Richard Pryor Show seemed to simultaneously explode and implode is another element worth exploring, a shining supporting theme better than the primary narrative. It takes a while for Peisner to lay the foundation for the start of In Living Color, but when he does it’s effective and clearly rendered:

Television was in its post-Good Times, pre-Cosby Show drought… The prospects for African-Americans in the film world were even drearier… This is the Hollywood Keenan, Arsenio, and Townshend were walking into.

There is some time given to Robert Townshend’s film Hollywood Shuffle, but not enough. That was a remarkable statement for independent cinema at the time (1987) about the paucity of authentic and respectable roles for African-Americans then and now. Again, it’s another example of supplementary characters and themes (Pryor, Eddie Murphy, Paul Mooney) that are really more substantial and interesting than this book’s subject matter. It goes back to shelf life and relevance, and Homey Don’t Play That stretches itself by probably 100 pages trying to justify a larger than necessary book about its subject.

The presence of such outlandishly gay characters as Blaine Edwards (Damon Wayans) and Antoine Meriwether (David Alan Grier) in the popular recurring sketch “Men on Film” definitely cannot be replicated in 2018. Whether or not it should be replicated is a different question. It was controversial at the time but it stayed, and perhaps that’s reflective of an era not straightjacketed (as some may see it) by political correctness. Other sketches, like “The Wrath of Farakhan”, starring Damon Wayans in a brilliant take on Nation of Islam leader Louis Farakhan on the set of a Star Trek film, are politically charged sketches that still resonate. Other shows at the time (namely Saturday Night Live) would not have touched this, or at least the end results would not have been as effective.

The cultural legacy of In Living Color was somewhat alien to white programmers at the time. Show writer Rob Edwards noted:

‘Black audiences don’t just laugh at stuff, we stomp our feet, we high-five… People were literally running up and down the aisles during the taping [of the show’s pilot], high-fiving each other. One of the executives turned to me and said ‘Did you pay these guys to do that?’

Homey Don’t Play That is exhausting in its detail, and that’s not always a good thing. Too much time is spent on recounting graphic details of what would now be clearly acts of sexual harassment posing as humor in the sketch comedy show office workplace. Not enough time is spent on how the show ended, how cast member Anne-Marie Johnson claimed “We were used as laborers to build up Fox, and once that was done, we were let go…” Later we read that “New York Congressman Ed Towns hammered Fox for what he perceived to be ‘plantation mentality.’ “

Peisner includes a quote from comic Marsha Warfield, who concludes that In Living Color “…anchored a whole new world not just for black entertainment but for entertainment period. It deserves its own place for being part of that revolution and evolution.'” That may very well be the case, but Homey Don’t Play That would have been better served in a different format, perhaps a coffee table book with full color photos, perhaps a pure oral history solely from those directly involved in the show’s production. As is, the book is a long read that takes up more room than it should and leaves too many narratives stranded by the side of the road. An author’s unlimited access to high profile interviews does not matter if it’s put to a narrative that’s juggling more elements than it should. Something has to come crashing to the ground.