No, The Hookah Girl is not a graphic novel about smoking hash in hookah bars and hooking up with “exotic” belly dancers. It’s an intentionally scattered memoir in comic strip form of a childhood and young adulthood navigating the cultural hazards of growing up Palestinian in the US.

Marguerite Dabaie‘s

The Hookah Girl is a physically small book, a 6″ x 6″ square, and most of its 17 sections fluctuate between three and five pages, with a few one-, two-, and six-page outliers. The first, an introduction rendered appropriately in comics form, explains Dabaie’s ten-year struggle to publish her memoir due to its apparently “provocative” and “overly political” content. One publisher turned it down for fear of being “firebombed” because of the first strip, a sequence of paper doll cut-outs to dress the cartoon figure of “Margo” as a hijab-wearing Muslim, a gun-toting Revolutionary, a harem seductress, a bomb-vested Martyr, and, finally, a Hungry Artist—the closest representation of her actual self: “I’m sorry to break it to you, but some Palestinians enjoy drawing and eating as well.”

The title strip, “The Hookah Girl”, is only seven panels across a two-page spread, describing a childhood memory of an annual Palestinian Day celebration where a woman carted around a rented hookah and smoked it all day. Both the woman (possibly Dabaie’s distant and unnamed cousin) and the event (which included carnival games and bouncing in an inflatable castle) seem unremarkable—which is likely the point. The so-called Hookah Girl isn’t exotic because she’s Palestinian. She stands out despite that. Although the rent-by-the-hour hookah caught Dabaie’s childhood attention, it’s the woman’s “hand cart”—what Dabaie carefully draws as a metallic dolly—that commands her memory now.

Though I appreciate the indirection of titling the book after the so-called Hookah Girl, “The True Arab Experience” and its subtitle “This handy guide will help you with the Arab-American lifestyle!” are a clearer indication of the collection’s goal and tone. Dabaie lovingly documents aspects of her family that feel peculiar to her while growing up in a larger US culture: speaking in an unnecessarily loud voice, mispronouncing letters, overstocking nuts and seeds, pointing with your head and eyebrows, eating grape leaves—a favorite food to be hidden from your non-Palestinian school friends.

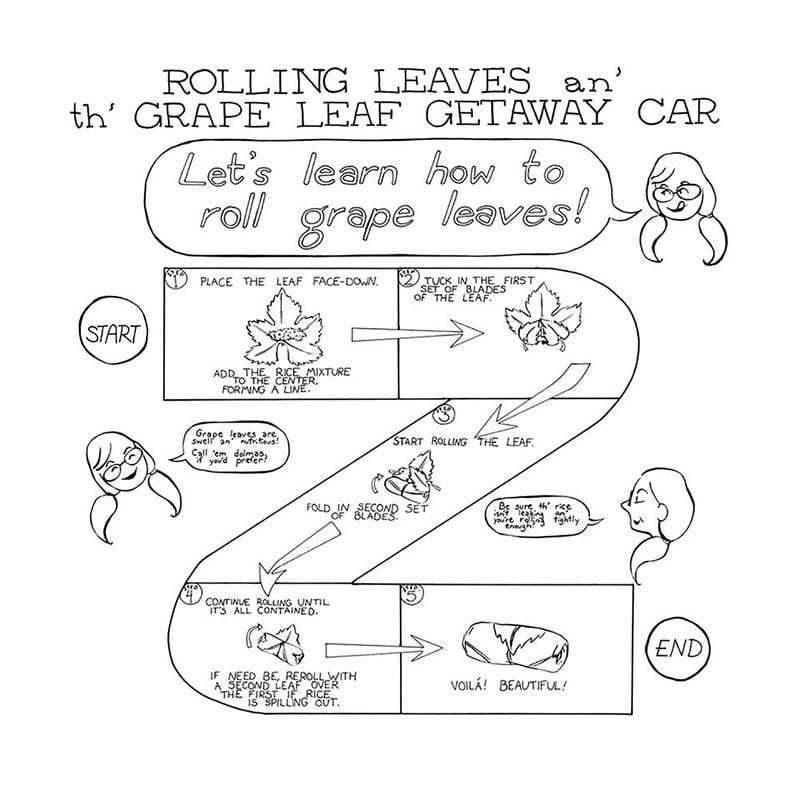

The next strip begins as a how-to guide for rolling those grape leaves, before revealing wider details—the aluminum on the TV antennae, the inexplicable garbage bags filled with the leaves—and then the even wider details of how the family drives at night to distant Napa valley grape orchards to snip off the leaves before chased by police. A traditional memoir would linger on the incident longer, answering many of the implied questions: How often did this happen? Was it unique to her family? Did it seem peculiar to her at the time or only afterwards? Dabaie instead jolts us to the next fragment.

Her accounts also aren’t always loving—as when she thanks her father for doubting her artistic skills (“This is all a waste. She’s only a girl.”) and so spurring her further away from the traditional feminine roles her family expected of her. She also longed to learn music, even trying to play her father’s oud and darbuka when he wasn’t home because he refused to teach her. He didn’t let her practice school instruments at home either because “girls just didn’t do those things.”

Dabiaie critiques mainstream US culture too—noting without naming her that Gal Godot, an Israeli actress who served in the military and supported the 2014 war in the Gaza Strip that left 2,000 Palestinians dead, plays a feminist goddess fighting to end war. Yes, Dabaie is dissing Wonder Woman—as well as a half dozen other beloved US films that portray Arabs as nonsensical cartoon villains. Yet she’s also enamored by Leila Khaled, an airplane-hijacking terrorist and/or freedom fighter—though Dabaie’s interest swirls around the woman’s contradictions as both a gender-breaking and gender-conforming celebrity.

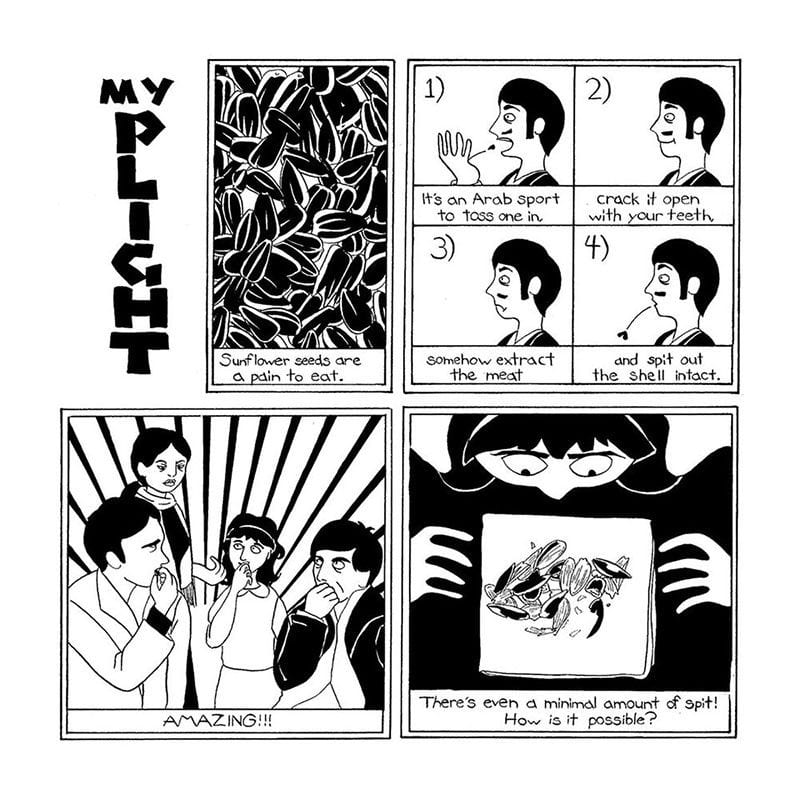

Whether you agree with Dabaie or not, her point of view is uncommon and so well-worth hearing. She names Palestinian cartoonist Naji Al-Ali as an influence, an exile who “antagonized everyone”. Though Dabaie’s comics are far gentler, she seems like an exile too, never quite at peace anywhere. Outside of her family home, she’s subjected to racist jokes, while inside it she is unable to master basic cultural skills—like extracting the meat from a sunflower seed with her tongue. She renders neither incident as especially harrowing—the joke-teller slumps off in embarrassment when told by someone else that Dabaie is “half-Palestinian”—but it introduces Dabaie as a “nus-nus”, or what she terms a “stealth Arab”, someone who passes as white but grew up Arabic. Much of her collection involves her trying to explain her culture to non-Palestinians readers, taking pride in textile art or mapping her Italian grandmother’s migration route into multicultural Palestine.

Much of her childhood involved similar attempts—though after her one-legged uncle began screaming inexplicably at her friends, she no longer hosted birthday parties at home. She ends the collection in her childhood too, with the statement: “I didn’t know what to believe,” a revealing refrain that encapsulates her split-culture and leaves her permanently mired in her past.

Dabaie is also a talented artist, who portrays herself and her family in an evolving array of styles that creates an underlying instability to her micro-narratives. While most of her renderings are simplified in a cartoon-sense, they vary between exaggerated caricatures and stripped-down naturalism, an appropriate stylistic span for a fragmented memoir about her own shifting identity. Even her page’s frames and gutters are unstable, sometimes decorative, sometimes solid black, sometimes open—further reflecting the memoir’s lack of a baseline reality.

Dabaie’s is a world in constant flux, unwilling to maintain a single style or even narrative thread for more than a half dozen pages. Her life must be gleaned in fragments instead and pieced together accumulatively. While gently provocative, The Hookah Girl is primarily entertaining, a brief but engaging glimpse inside one artist’s dizzying life experiences.