Volume 4 in Film Movement’s Joseph W. Sarno Retrospect Series pairs one of his most famous and groundbreaking films, Sin in the Suburbs (1964), with simply one of his best, Confessions of a Young American Housewife (1974). Their ten-year separation reflects a whole era of development in that middle-class phenomenon called the Sexual Revolution. Thrown in as a kind of bonus is Warm Nights Hot Pleasures (1964), the film made immediately after Sin in the Suburbs.

In American cinema of the ’60s and early ’70s, there were three ways of presenting themes of characters having sex. The mainstream Hollywood way was generally not at all, although this was changing as censorship boundaries were gradually expanded by indie exploitation movies, often at considerable legal expense.

Theirs was the second way: present sex titillatingly while appeasing local censor boards with “socially redeeming value”, which meant meting out harsh puritanical punishment to those who strayed from the married missionary position. In other words, sex was kept safely dirty and shameful. This explains, for example, the ending of John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy (1969), the first major Hollywood production under the MPAA’s new X rating to win an Oscar for Best Picture. If that film feels like a downer, that’s how America wanted its hustlers. The likes of Xaviera Hollander, “the Happy Hooker”, was still a few years away, awaiting the arrival of the short-lived “porno chic” era.

Whereas Sweden was commonly held up as a political-economic “Third Way” between the capitalist West and the communist Iron Curtain, the budding or chafing sexual revolution in cinema was having its own Third Way in the form of Swedish-American filmmaker Joe Sarno, whose idol was Ingmar Bergman. Sarno made films that, while adopting an intense (and cheap) style, explored dramatic and credible arcs of character and plot in which sexual liberation was generally held a good thing, it’s just that many people’s traditional guilt-ridden hang-ups couldn’t handle it.

The Swedish influence on sexual cinema was pronounced, not only in Bergman’s films but, for example, in Vilgot Sjöman‘s scandalous I Am Curious (Yellow) (1967) and I Am Curious (Blue) (1968), whose landmark court cases were spurred by distributor Barney Rosset. These films created an uproar not really so much for brief moments of softcore sex — though that was why most tickets were purchased — but for their “socially redeeming context” of socialist critiques and the fact that their liberated heroines weren’t punished for enjoying themselves sexually. Sweden had such a cutting-edge attitude that Sarno made several films there, including the hit Inga (1968), and found it personally liberating to discover professional production values along with stage-trained actors who had no objection to nudity.

And that brings us to this Film Movement’s Blu-ray, which contains films made before and after Sarno’s Swedish period. In my PopMatters review of Film Movement’s first Sarno volume, I observed “tight close-ups of angst-ridden neurotics who talk without facing each other, a general sense of isolation underlined by lighting and composition, and softcore gropings scored by percussion. [The work] also concentrates almost entirely on women, with men as disposable pretty playthings in women’s often intergenerational power struggles for their sexual identity.” Except for the more expansive musical scores, I can say that in spades regarding the two main entries here, and it’s exhilarating.

Sin in the Suburbs / Warm Nights Hot Pleasures

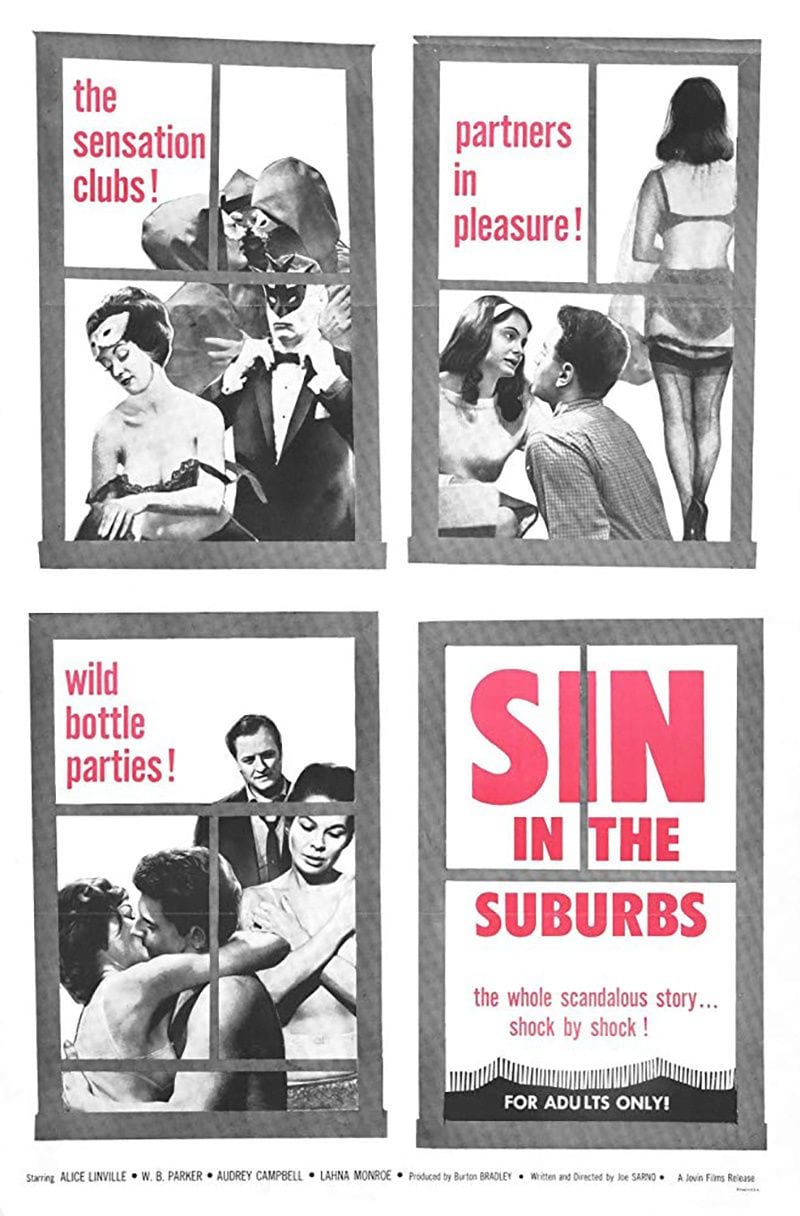

Sin in the Suburbs premiered in February 1964, the month after Time Magazine‘s 24 January cover story on “The Second Sexual Revolution”. Talk about zeitgeist. It was also the year after Betty Friedan‘s The Feminine Mystique transformed the bored and frustrated housewife into a cultural talking point, at least among the serious and pointy-headed.

If we look more closely, that housewife had been making her stealthy case for a while, for example in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 back in 1953. While supposedly set in the future, Bradbury’s work is, like most futuristic sci-fi, a metaphorical vision of “the way we live now”, and while Montag’s wife is a minor character, she exists to demonstrate that when women are kept at home, doped up and told to be happy, the result is spiritual catatonia and misery that contrasts sharply with the independent woman who catches Montag’s eye. Francois Truffaut‘s 1966 film version cannily casts the same actress (Julie Christie) in both roles, implying that the only important difference between them is whether they accept their social control or reject it.

The 1950s’ most popular TV show, I Love Lucy, is essentially about the machinations of a desperate housewife to fulfill her thwarted creative impulses. I think it’s significant that the contrasting family sitcoms about sensible housewives couldn’t compete, despite their insistent proliferation. Should we feel grateful or disappointed that no enterprising satirist has yet graced us with a Sin in the Sitcoms, where the Ricardos, Cleavers, Andersons and Stones somehow show up at the same tweedy pipe-and-apron spouse-swapping hoedown?

In 1960, Irving Wallace’s bestselling novel The Chapman Report titillated readers with the transgressive sex lives of suburban wives, and this got filmed as George Cukor’s 1962 movie. Like Time Magazine, it weaves the pop sociology of sex researchers into the mix; this was also a common strategy of sexploitation films, as bearded men in glasses and white jackets tried to inject “socially redeeming” lectures into the proceedings. Thank heaven for science.

All this is to establish that Sarno was in the thick of his cultural moment when Sin in the Suburbs began its highly profitable rounds. With his typical brutal edits and claustrophobic two- and three-character compositions, the story cuts between three neighboring households, each sexually unhappy in its own way.

With nothing to do while her husband is at work, Lisa (Marla Ellis) drowns her boredom in alcohol and affairs. The self-possessed Yvette (Dyanne Thorne) and the effete, saturnine, demonic Lou (W.B. Parker) pretend to be sister and brother to disguise their outlaw morals. This leads to their founding a masked sex club that you’d better believe must have influenced Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), as it’s the only element in that film that doesn’t have a connection to Arthur Schnitzler‘s source story, Dream Novella. In Sarno’s film, the black and white photography becomes especially high-contrast, mobile and suggestive during the masked parties, which are like satanic Tupperware gatherings.

The central drama or trauma belongs to the Lewis family, whose dull and absent paterfamilias works in “the plastics line” three years before Benjamin is advised to take it up in Mike Nichols’ The Graduate (1967). While hubby’s away, mom Gerry (Audrey Campbell) has for years invited guests over, sometimes more than one at a time, for fleshly pleasures. Sullen high school daughter Kathy (Judy Young) has been aware of this, and her burgeoning womanhood now threatens to “date” the resentful Gerry just as Kathy’s contempt for her becomes harder to mask. This is all part of why masking and unmasking is such an effective visual symbol.

It turns out that Kathy, while repelled by her nominal boyfriend (the mom has no such problem with him), needs to be lured out of the closet in recognition of her lesbian impulses, and Yvette helps with that before the big mother-daughter confrontation at a masked orgy towards which the narrative has been winding sedulously and inevitably. A well-buried subtext is that Kathy’s anger toward Gerry may stem from a child’s sense of being unwanted and that this starvation of affection may reveal a jealousy of her mom’s sexual partners, who can know Gerry in a way she cannot. This idea will be less submerged in Confessions of a Young American Housewife.

This print, previously released by Something Weird in a full-frame presentation that unmasked (that word again) the full image, is now masked at its original theatrical ratio of 1.78:1, thus keeping virtually all exposed breasts safely out of frame. The 2K digital restoration is so sharp that we can now clearly read many titles on Yvette’s bookshelf: Katherine Anne Porter‘s Ship of Fools, Rebecca West‘s The Fountain Overflows, Mary Renault‘s The Bull from the Sea and one of Bruce Catton‘s Civil War books. We can only wonder how random are these uncannily telling comments.

The original Something Weird commentary by Joe and Peggy Sarno, in which their memories are prodded by Mike Vraney and Frank Henenlotter, has been retained and supplemented with a new historically oriented commentary by historian Tim Lucas. (Full disclosure: Lucas is my former editor at Video Watchdog.)

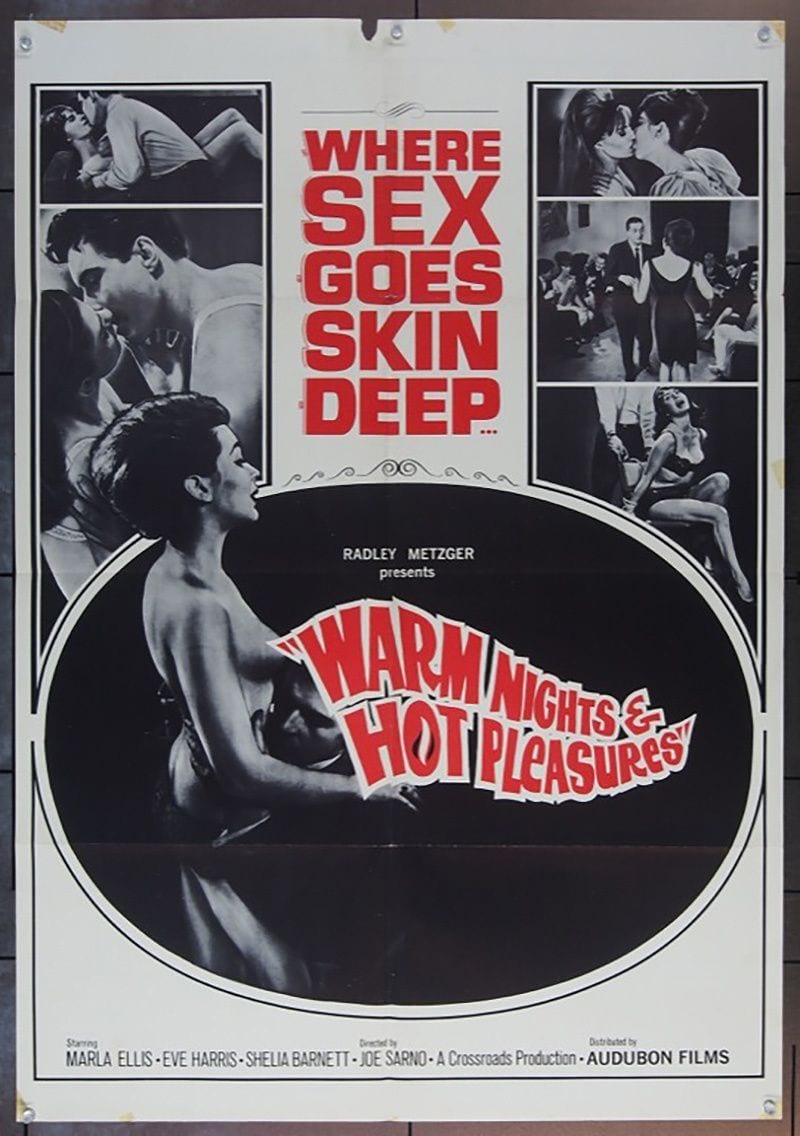

Warm Nights Hot Pleasures (1964) gets short shrift as the minor work it is, though it’s very Sarno. The basic situation finds three naïve college girls (including Ellis) deciding to pool their resources and run away to New York to break into show biz. This hardy plot has been trod dozens of times, of course. The mainstream Hollywood version was parodied by the old Saturday Night Live skit “Married in a Minute”, in which squeaky-clean heroines find true love. The crueler 42nd Street indie version, propelled by that “socially redeeming” albatross, invariably found such women ending up as drug-addicted prostitutes who get run over in the street.

And then, as usual, we have Sarno, in which nothing terrible actually happens, and in fact the women do indeed find work, yet we’re left with a depressing feeling of an exploitive milieu that feels as though Sarno were honestly writing from life. It turns out that “being friendly” with sleazeballs really does get paying jobs, so the movie ends with the question of whether you think that’s worth it. The different paths taken by the heroines leaves an ambiguous resolution. One sleazy role is played by Sarno’s cousin Joe Santos, later a well-known TV actor and a regular on The Rockford Files.

As Lucas points out in the accompanying booklet, this was Sarno’s only film distributed by Radley Metzger’s Audubon Films, and a print was only rediscovered in 2017 in Metzger’s estate. In fact, a slightly longer print has even now been discovered. This obscure and elusive era in adult films is still having its history rewritten and, as it were, uncovered. (It’s the nature of this topic that “as it were” keeps popping up.) Also notable is that this film has a sympathetic if lonely lesbian character, thus reminding us that Metzger’s Therese and Isabelle (1968) was way ahead of its time in American cinema as a non-judgmental and gorgeously stylized lesbian romance that probably still hasn’t received its due.

Confessions of a Young American Housewife

The disc’s crowning jewel is Confessions of a Young American Housewife, shot in attractive color in somebody’s duplex, the domestic scenes interspersed with walk-and-talks amid the sylvan glades of a public park. Sarno’s typical structure combines highly schematic development of themes with a very loose sense of passing time and connections between scenes. Dare we say, it’s an impressionistic or Bergsonian structure of personalized highlights that stretches time to its own purpose, as cast adrift from the larger world yet inherently reflecting it.

Lucas offers another commentary, beginning with a dramatic assessment: “Confessions is one of the hottest films Joe Sarno ever made, so it stands to reason that it must be one of the hottest films anyone ever made. Authentic sexual communion isn’t even something that hardcore adult films require. As long as an adult film shows penetration, it keeps its promises. However, Confessions of a Young American Housewife is a rare softcore film that surpasses the heat and chemistry found in a good 90% of hardcore cinema. Its erotic power isn’t a product of suggestiveness or even directorial style but rather directorial invocation. Sarno cast the film and provided a safe environment in which the following was encouraged to happen, and what happened was often startling in its erotic intensity.”

Although this isn’t a hardcore film, Sarno’s cast are famous hardcore actors also noted for their unusually professional acting skills. Under her real name Mary Mendum, Rebecca Brooke’s Broadway credits include the original productions of Milos Forman’s Hair and Bob Fosse’s Lenny, in which she played the role played by Valerine Perrine in the 1974 film version. Her character’s neighbors are played by real husband and wife Eric Edwards and Chris Jordan, both alumni of the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, who also carried on legit careers as Rob Edwards and Kathy Everett in TV commercials and other venues. Jennifer Welles was a professional dancer who studied acting with Sanford Meisner and entered porn after age 40, becoming very successful.

In other words, they belong to a vanished species of actor in the “porno chic” era when, after Gerard Damiano’s Deep Throat (1972), hardcore porn was briefly shown in some mainstream theatres and hardcore films made some effort at professional production values and storytelling with wildly variable results. That era effectively ended the market for Sarno’s preferred form of softcore drama just as he was arriving at a high point demonstrated by Confessions of a Young American Housewife.

A brief commentary by the late Sarno recalls the film and its actors fondly, and he also states that he approved of the social trend toward non-exclusive and non-marital relations among young people. He further states that when he was in high school before WWII — and it was in the military that he learned filmmaking, like his fellow pioneer Russ Meyer — he became aware of two unrelated classmates who were having sexual relations with a parent, and he concluded that incest was more common than supposed, and this is why the theme manifests so often in his films. Confessions of a Young American Housewife doesn’t include lesbian incest, yet its possibility or “threat”, if you will, is even more consciously pronounced than in Sin in the Suburbs.

The film follows the deoxyribonucleic plot strands of mother-daughter heroines. Carol (Brooke) is introduced having a kaffeeklatsch with neighbor Anna (Jordan) when they’re visited by some other young housewife unknown to them. This sprightly visitor has an appointment with Carol’s husband Eddie (David Hausman), and she assumes Carol must be Eddie’s sister; remember the false siblings in Sin in the Suburbs. Amusement ensues when Eddie arrives and realizes he’s been caught scheduling a fling while his “broad-minded” wife was supposed to be out.

Things don’t take the expected turn, however, as the film hints and feints at their reality. Carol and Eddie, along with Anna and her husband Peter (Edwards), belong to a “foursome” and frequently get together in “combinations too numerous to mention”, a phrase that constitutes the movie’s only hint at male bisexuality. The potential flaw in the ointment is that despite this “broad-mindedness”, Eddie evidently plays further without Carol’s knowledge.

Arriving for a visit is Carol’s widowed mother, Jenny Robinson (Welles). If Sarno anticipated the plastics of The Graduate in Sin in the Suburbs, he now openly refers to that movie with a very robust Mrs. Robinson, who got married at 17 and is now 37, making Carol about 20.

Carol believes that Jenny must be kept in the dark about her activities. The orally fixated Anna, whose running joke is that she’s constantly eating high-caloric foods and saying whatever comes into her head, asks if Jenny doesn’t know it’s 1974. Carol assures her that Jenny embodies, as it were, a previous era’s ideal housewife ever since being named Young American Housewife of 1963 (the year before Sin in the Suburbs) by a magazine called Domicile Beautiful. This takes a poke at such real consumerist magazines as House Beautiful, Better Homes and Gardens, Good Housekeeping, etc.

Jenny certainly does bake lots of pies, which delights Anna, who complains that her mother was the worst cook in the world. A Freudian would make much of her insatiable oral appetites, which lead her to declare her love for Jenny in a late scene. This parallels the more submerged erotic tensions between Jenny and Carol, who has always felt herself in her perfect mother’s “shadow”. Her fear of her mother’s overhearing their activities, which evolves into a desire that she overhear, may reflect a girlhood of overhearing her parents and her concomitant sense that they had a private life that didn’t revolve around their daughter, and which again may be a source of jealousy and unfulfillment.

This is a lot of ambiguous and unresolved weight, and I haven’t limned the half of it. In the film’s first group encounter scene, Carol’s fears at her mother overhearing are resolved when Peter suggests they retire to his house. At first Carol says something about not wanting to leave her mother alone but then she nods and agrees.

So we’re to understand that they’re next door when the film cuts to some little room with a mirror on the wall, in which the noisy foursome begin “devouring” Carol as Anna goads her with a fantasy about the memory of “sucking on your mother’s tits” and “getting the milk” (something of particular interest to the food-oriented Anna) and Carol begins shrieking “Mama!” not unlike the daughter in Sin in the Suburbs. Our conclusion is confirmed when the film cuts to Jenny emerging onto her darkened landing (with a glass of milk!) calling “Carol?” and being answered with tomb-like silence. They’ve turned off the lights and abandoned her for their pleasures, thus reversing the situation of Carol’s childhood.

The men noticed right away that the buxom Mrs. Robinson wears no bra, thus implying that she wasn’t as uptight as advertised. As is often the case with Sarno, a character who’s supposedly prim and proper proves a dormant tiger (or cougar) waiting to be unleashed, and one of the film’s most uncomplicated pleasures is Jenny’s unapologetic exploration of newfound delights, including lesbian interludes. She asserts that she loves “every spasm, every quiver, every orgasm”, rapidly almost outstripping (as it were) her daughter. She also courts a healthy interest in a wounded young “delivery boy” abandoned by his wife; he’s played with innocent radiance by an uncredited tall handsome fellow with fluffy hair.

So the film begins with “confessions” by Carol, whom we assume is our titular young American housewife, and then gradually reveals that Jenny had been officially crowned with that title, and she eventually makes her own “confession” that potentially usurps her daughter’s centrality from the story and leaves her “in Mama’s shadow — again”. The more experienced Jenny, at the beginning of the film and again at the end, utters the hardbitten philosophy that “nice things don’t last”. She may be better able to handle this new permissiveness than the younger generation, who didn’t invent sex.

Although this is a resolutely non-tragic comedy of manners and mores, the film underlines Carol’s hollow emotional space even as she’s surrounded by happy idiots who intend to keep on truckin’. The final exchange between mother and daughter is a hopeful one with a necessary declaration of love as Jenny makes a decision that startles them all. The closing images find Carol mocking model photography by adopting a series of campy poses as the others look on, as though implying that their consumption of such images and idealizations pervasive in culture creates a self-consciousness and an insatiable hunger that keeps them going through all possible motions — “too numerous to mention”.

If one secret to Sarno’s success is his careful tracings of credible psychological relations and their potential problems, another lies in his method of directing actors to go as far as they like sexually even though any “action” will fall outside the frame as he focuses of their faces. Watching the film, we easily believe that the actors are indeed not acting, or rather that they’re enacting their characters in the same sense that Fred Astaire enacts a character while he’s dancing. The sexual chemistry and behavior is actually happening, and this resonates with what the camera sees while leaving lots of imagination to the viewer. Softcore movies, not to mention mainstream sex scenes, simply aren’t staged like this, and yet Sarno avoids explicit imagery aside from decorous nudity.

If Sin in the Suburbs and Confessions of a Young American Housewife are two of Sarno’s best movies, and they are, then this fourth volume in his retrospective must be the best of all, and it is.

- A Beginner's Guide to Exploitation - Dream Follies/ Dreamland Capers

- The Return of the Popcorn Circus: August 2008 - PopMatters

- The Implacable Progress of 'Porn'

- Tricks or Treats? Ten Halloween Blu-rays That May Disrupt Your Life ...

- The Essays in 'Sex Scene'

- The Sultan of Sophisticated Smut: Joe Sarno (1921 - 2010)

- A Life in Dirty Movies

- Sex in 1968: A Joe Sarno Double-Shot - PopMatters