New York City’s Lower East Side—the storied quarter feared and celebrated for two centuries, home to a series of immigrant populations and numerous civic, industrial, and cultural practices designed to exploit or reform them—gave rise to artistic practices and ways of seeing at the foundation of modernism. So argues Sara Blair in her sweeping survey of representations of the region.

Blair’s title, How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York, alludes to Jacob A. Riis’s 1890 exposé that featured his groundbreaking flash photography of the area. Riis, photographers Paul Strand and Walker Evans, writers Stephen Crane and Abraham Cahan, filmmaker D. W. Griffith, poet Allen Ginsburg, saxophonist Sonny Rollins, and artist Martha Rosler are among the documenters of the Lower East Side whose work re-envisioned how the quarter was represented and in so doing changed their fields of expression.

It’s an ambitious, if at times amorphous, project, but one that Blair for the most part pulls off in impressive fashion.

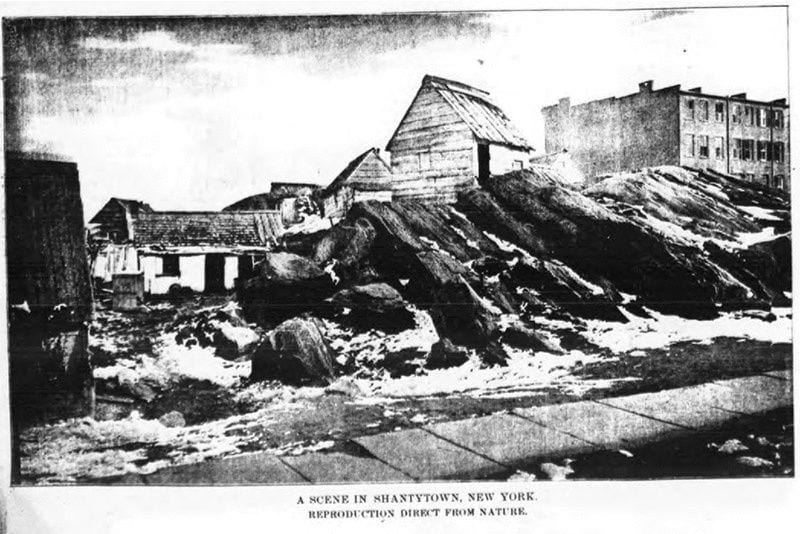

In March 1880, the first halftone image—printed with a new technique capable of reproducing the full tones of a photograph—appeared in an American newspaper, the New York Daily Graphic. Blair makes much of “A Scene in Shantytown, New York”, a view of dilapidated buildings thought to be photographed downtown, near Pearl Street. The image and the circumstances of its publication nicely capture the major themes of How the Other Half Look.

First, the subject matter and title harken back to the slums of old New York and conjure all of their connotations of squalor and vice, despite the fact that shantytowns had been mostly demolished by 1880, replaced by the tenements documented by Riis. That is, the Lower East Side quickly became as much a mythic construct, shorthand for a cluster of reactionary and progressive views of the city and its poorer citizens, as an actual place. Second, every new way of seeing the Lower East Side brings with it the promise of heightened fidelity to an experience that the format nevertheless depicts as alienated and alienating.

Third, the Lower East Side is more often than not one of the first locations for deploying such technologies and perspectives, which forever bear the trace of that original use. Finally, representations of Lower East Side subjects serve a double function for those who consume them, as calls to action or vehicles for virtual tourism: “entertainment and enlightenment, evidence and spectacle”, as Blair says of the images Riis published in books and periodicals or projected in magic lantern shows.

Blair teases out a number of themes from the work of the artists she examines. Again with respect to Riis, she establishes the play of “animation” and “arrest”: the consumer of photographs and other representations “is animated by a heightened sensory experience of the slum” while “its visible figures are arrested, caught in iconic gestures or displays of the intransigence of their condition”. Blair’s themes transcend art form; she finds this effect in Crane’s 1893 novella Maggie: A Girl of the Streets as well. The novel’s characters, a composite of stock characters from reform and naturalistic literature of the US and Europe, are “imprisoned” not just by the slum, but by “the emerging conventions … of its visualization”.

“Emptiness” captures the import of the images produced by Walker Evans, a feature Blair ascribes to his work in the Lower East Side, by the 1930s no longer the site of the teeming masses of the turn of the century due to economic depression and strategies of urban renewal. Often devoid of human subjects, Evans’ photographs depict relics, traces, incoherent signage: “absence and loss”. Novelist Henry Roth, author of Call It Sleep (1934), and printmaker and photographer Ben Shahn find in this emptiness fertile ground for exploring the past and future of Jewish American experience.

Blair’s case for the Lower East Side as a “camera obscura” for partially capturing “evanescent truths” is less convincing. In her lengthy elucidation of Allen Ginsburg’s “Kaddish“, the long poem occasioned by the death of his mother, she argues that this metaphor resonates throughout the poem, with its emphasis on visionary experience, but fails to ground it in the specifics of the verse. Here and elsewhere Blair’s riffing on various artists’ representations of the Lower East Side can veer off into a muddled metaphoric register that contrasts sharply with the many passages in which she effectively marshals specific examples to support her assertions.

Blair is much more convincing when she mines artists’ biographies and commentary for evidence of how they saw the Lower East Side, than when she engages in close readings of their work. Much more compelling than the Ginsberg section is her assertion that in their search for urban spaces free from encroaching gentrification, writer Amiri Baraka, multimedia artist Ted Joans, and saxophonist Sonny Rollins found the Lower East Side the perfect space for “evolving figurations of the ‘wild’, the unassimilated, and the untamed”.

“Remediation”—”the project of replacing one medium with another through representation of the precursor’s logic or effects” helps Blair explicate the August 1950 issue of the weekly magazine Collier‘s that imagined a nuclear attack on New York City. In “Hiroshima, U.S.A.” other parts of the city survive the blast, while the Lower East Side is obliterated. The feature employs tropes used to describe the region since the mid-19th century, from Bowery bums to the language of wounding and decay (the blast has left the quarter “a monstrous scar defiling the earth”). Accompanying images, eschewing photorealism, call attention to themselves as illustration and hearken back to drawings displaced by the halftone reproductions with which Blair began the book.

In a coda, Blair offers one final example: the climactic scene from Jeff Orlowski’s 2012 documentary Chasing Ice, in which lower Manhattan is superimposed on the edge of a crumbling glacier. For Blair, this effect evokes the Lower East Side’s “historical image repertoire, in which threats of disaster and the imagination of American perfectibility are inseparable.” In this case, the connection to the ways of seeing Blair has tied to the Lower East Side feels like quite a stretch. As Blair herself admits, the strategy more clearly resonates with Americans’ memory of 9/11, imbuing the threat posed by global warming with the emotions elicited by global terrorism.

That’s not to say that Blair’s thesis loses relevance as her analysis approaches the present. The locus for competing views of immigrants as unassimilable, bestial others (the Mexican immigrants of Donald Trump’s imagination) or families in search of a better life has of late shifted to the southern US border. To see the issues of representational fidelity and the power of the image that emerged from the Lower East Side at play in the immigration debate, look no further than the 2 July 2018 cover of Time magazine depicting President Trump looking down at a crying child, with the words, “Welcome to America”.