The essential nature of testimony is that it comes with a price. Few things worth telling come without consequence, and the greatest indicator of a hero is not when they tell the story but that they tell it at all. In the Afterword of We’re Still at War: Stories of the 20th Century, Post Bellum Director Mikuláš Kroupa notes the significance of Art Spiegelman’s Maus in his understanding of the obligation to tell stories, in whatever form proves most potent.

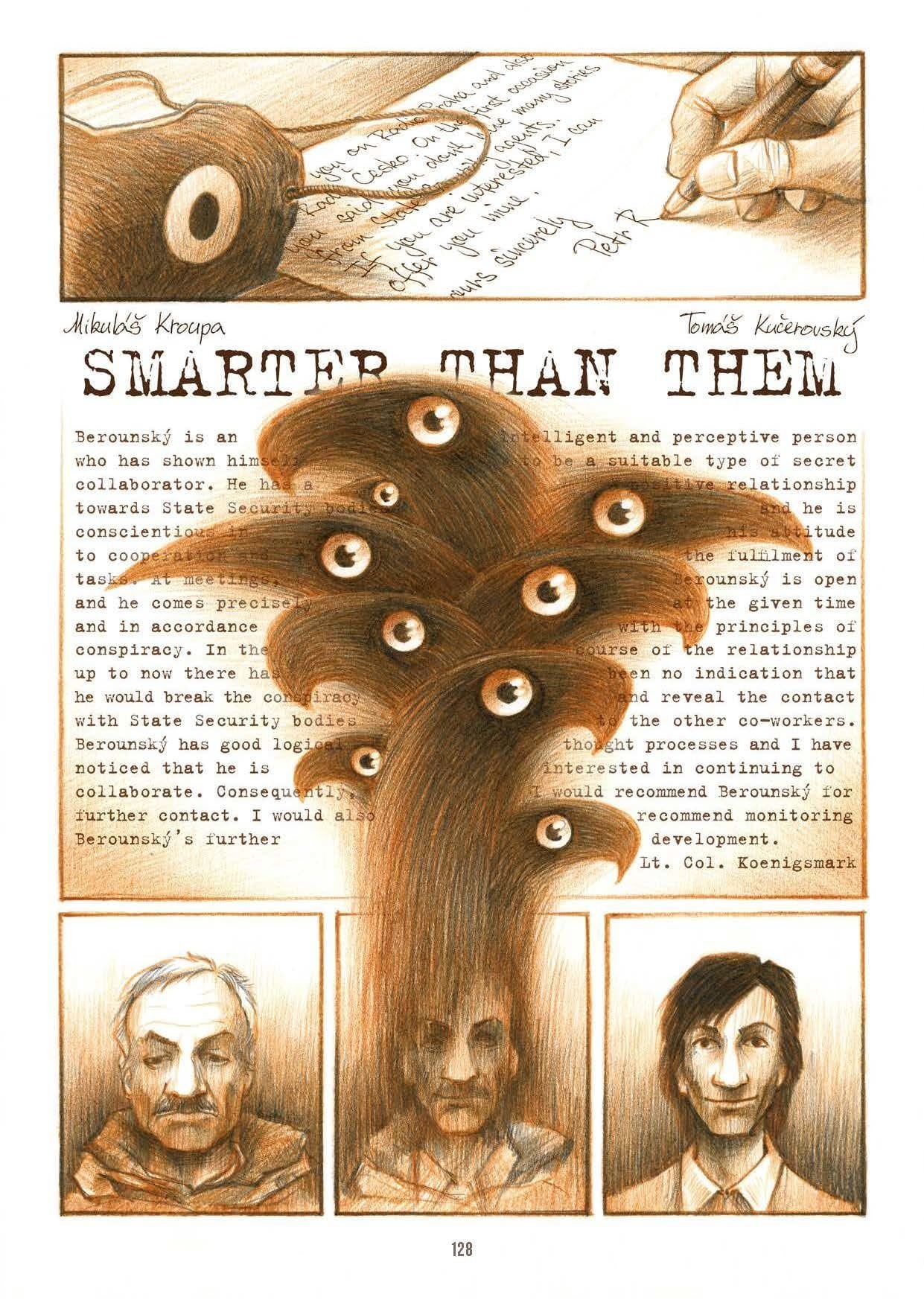

For Kroupa, Post Bellum’s mission of collecting testimony from war veterans, Holocaust victims, and opponents of Nazism and Communism (especially as manifested in the Czech and Slovak regions during WWII) also had to incorporate perspectives from Communist Secret Police and scores of other collaborators. The mission is not simply to isolate testimony from those who suffered, but to also shed light on those who worked against the smothering constraints of fascism and totalitarianism.

Kroupa explains what Spiegelman’s Maus proved for him when he read it while in the hospital recuperating from an undisclosed illness:

“Until then I had thought that the comic format made for second-rate, holiday reading… [the book proved] a comic book can tackle a serious topic and a personal testimony in a meaningful way.”

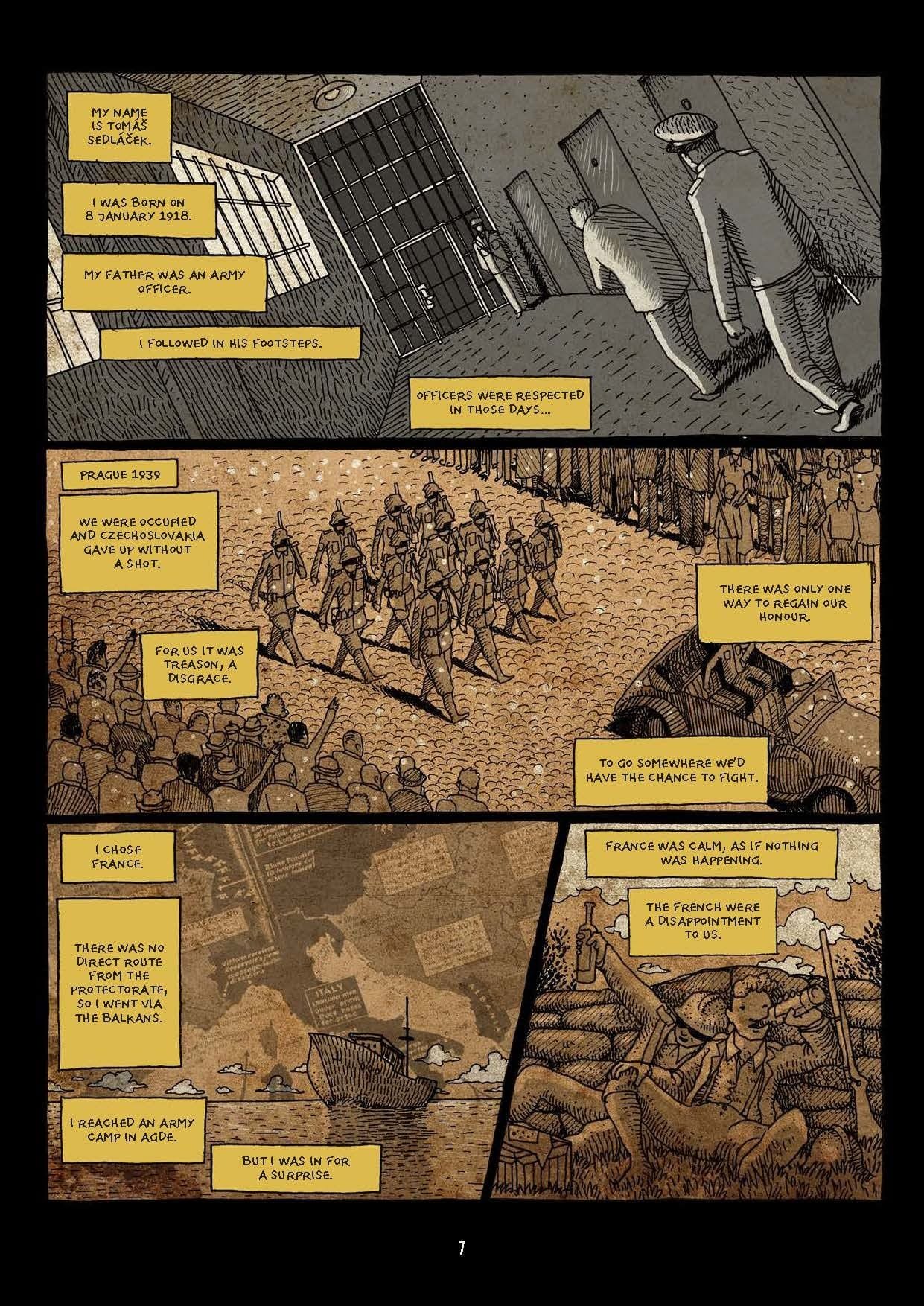

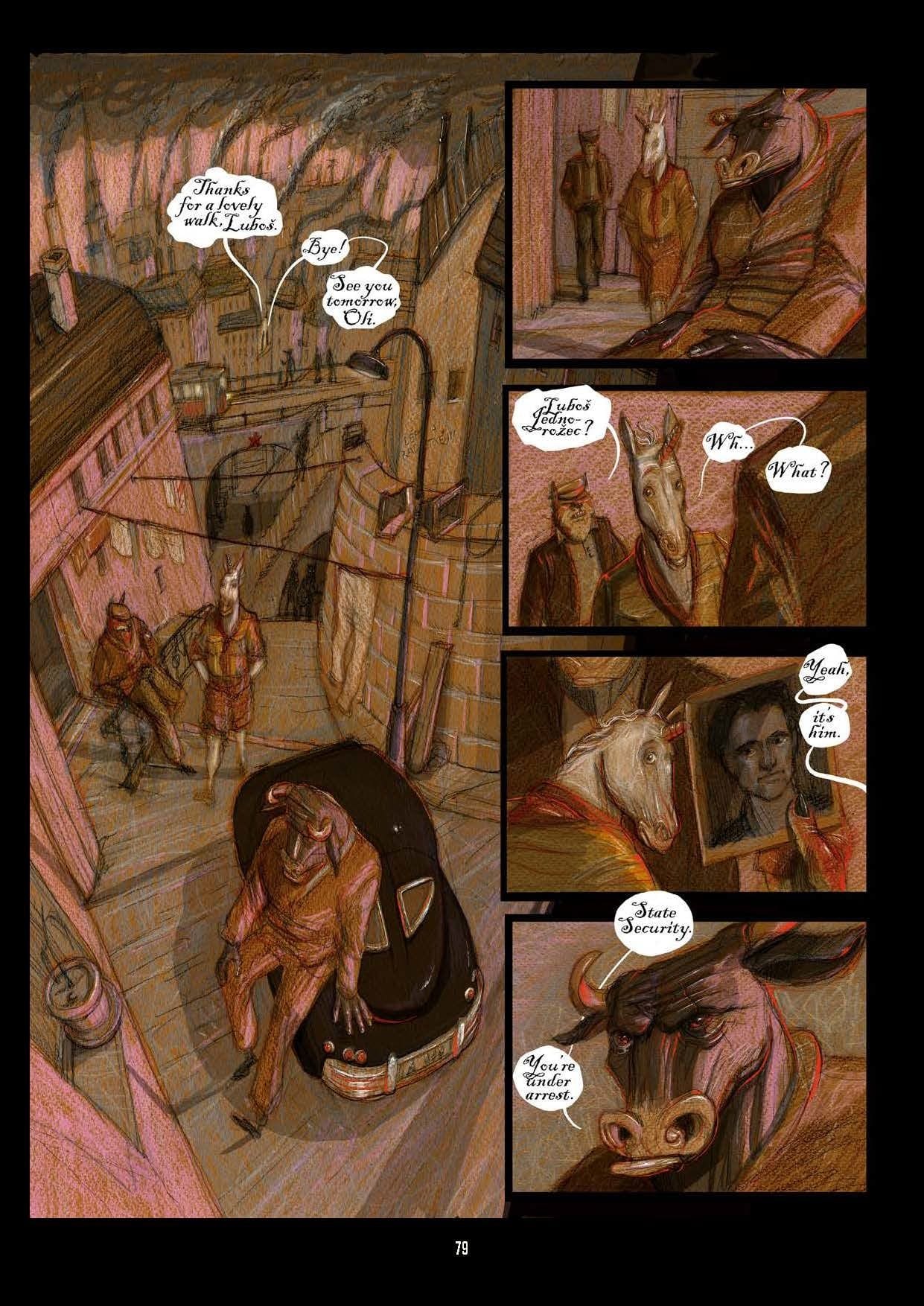

What we see in We’re Still at War is a collection of 13 varied graphic tales, written and illustrated by a variety of Czech and Slovak artists, including Miloš Mazal, Branko Jelinek, and Jan Bažant. These artists and their stories testify to victories and defeats, weakness and heroism, how the smallest acts of kindness can make a difference even in a world of unbearable pressure and pain. The importance of a text like this in a time like ours cannot be understated. We know that the Communist regimes of Europe collapsed nearly 30 years ago, and that the Third Reich dissolved at the end of World War II. The rise of right-wing extremists and white nationalists in those days through now is, sadly, nothing new.

As for the articles , they appear in various styles and formats. “The Boy’s Done Nothing Wrong” is a haunting, full-colored collection of images, like a cinematic storyboard, “The Adventures of Hurvinek” is a bright comic about a man named Leopold Farber, who spent the ’60s collecting stories of those who survived, and those who fought back (fruitlessly or not.) Editor David Barton writes “In his narrative, Leopold, is perplexed by the persistence of pointless and extraordinary cruelty.” In “The Last Flight”, the visuals seem to have been carved from something unyielding. They’re kinetic, frightening, in keeping with the story of a group of young people who attempt to steal a plane from a small airfield and fly west.

There’s no understandable arc to this anthology, no apparent reasoning for the positioning of the stories, but that doesn’t minimize its power or importance. “Massacre at the ‘Murdered Man’: The Life of Ruda Bělohoubek”, is another dramatic and brutal story perfectly realized, especially when we see the photo of the real-life Bělohoubek at the end, posed in a chair with his grizzled grey beard, clutching a rifle and ready to use it, no questions asked. Writer Adam Drba explains the importance of Bělohoubek’s story:

“The story… adds a human perspective to this traditional interpretation. A little boy loses his mother and father to an angry mob… in the turmoil of May 1945… The theory of ’cause and effect’ is monstrous… it [this story] shows how saturated Czech society was with cruelty from all it had suffered during World War II.”

It’s probably safest to say that the best and strongest recurring themes in these stories are not overwhelmed by the variety of visual styles. Some of them are discrete, calculated, and almost bright in their all too common banality of evil. Others are kinetic, disturbing, bathed in watercolor or hidden in the infinite shades of grey. It’s certainly a vivid spectrum of representation as the visual artists try to match the verbatim testimony of the survivors. In several instances, the editors were able to collect these stories just in time…

The difficulty in assessing the literary merits of such a volume rests in the mission of Post Bellum itself. The documentarians working for this Czech non-profit recorded these memories from survivors during 2001-2011. The recordings are stored in the Memory of Nations website. Kroupa writes: “No one censors us; no one gives us orders. When producing the programmes we abide by our own consciences, by the words of the narrator, and by the advice of experts.” While this is a noble and necessary mission statement for documentarians, it can make for an inconsistent reading experience.

Where Spiegelman’s Maus benefitted from a singular vision and a purely defined voice from start to finish, We’re Still at War suffers (albeit slightly) by comparison. Some of the 13 chapters (particularly those mentioned here) are forceful but others stumble to find a narrative center. Nevertheless, this is a collection that deserves a visible place in the growing bookcase of graphic narratives that testify to the precarious balance between human atrocities and admirable perseverance.