The resilience of a pop song anthem may not always be obvious on paper. Lyrics are scribbled on stationery from the New York Hilton. They’re hasty, immediate, three verses that seem to be the basis for something, but on paper they’re not much. They’re just four lines suggesting the listener/reader to consider alternatives, and the fifth resolves on a universal level: “Imagine all the people…” When a peaceful pop song comes across as a suggestion, it’s easy to follow this lead. Imagine everybody living for today, living life in peace, and sharing all the world. There’s a bridge in this song, after the second verse and as a resolution after the third. Well-crafted pop songs would be nothing without a bridge to take us from here to there. John Lennon’s 1971 classic, “Imagine” would be nothing without this bridge. In it, Lennon admits that he is probably not much more than a dreamer, but there’s nothing to risk if we go along for the ride. All he wants is for us to believe in the potential for change.

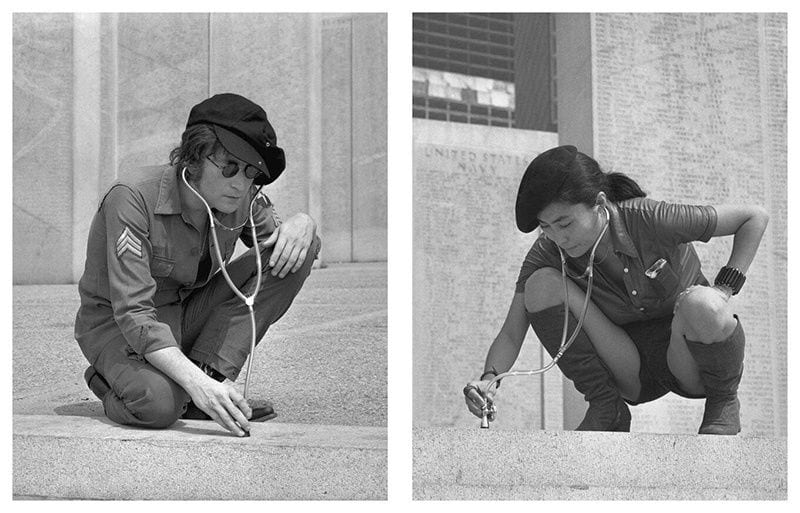

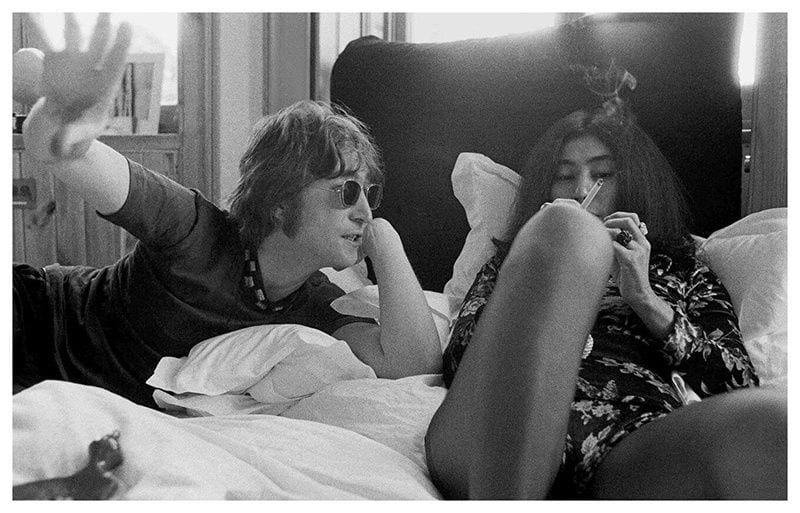

Imagine John Yoko is a lovingly curated coffee table book about the roots of the album, Imagine (Apple Records, 1971), the art created within the world they’d created in and around their Tittenhurst estate. This was the pre-Dakota Building New York City John and Yoko, the couple between the sonic wall of “Instant Karma”, the primal screams of “Mother”, and the radicalism of “Power to the People”. In short, that song was probably the calm before the storm. This book covers the roots of the song, album, film, merchandising, and philosophy behind “Imagine”. The tragically interrupted life and times of John Lennon is matched in its power by the resilience and audacious optimism of Yoko Ono. From the sexism she faced in her pre-Lennon life as an avante-garde performance artist, through the racism she faced once she met and connected with Lennon, to accusations of her being a “professional widow” after his 8 December 1980 murder, Ono has steadfastly and respectfully maintained Lennon’s legacy while defining more avenues where she’s taken her art in the nearly four ensuing decades. If anything should be taken from this book, it’s that “Imagine” — the song and everything behind its creation — was a truly collaborative effort.

Indeed, Ono is our host through the course of this book, and while she has always had to brave a degree of resistance in her public life, she doesn’t intrude too much through the text of Imagine John Yoko. She has curated a series of testimonies from various key players originally involved with the project. “The third verse came to me in an eight-seater plane,” Lennon recalls in an excerpted transcript of a BBC radio interview originally broadcast on 6 December 1980. In a key passage from that interview, Lennon admits that “Imagine” was greatly inspired by Ono’s 1964 book, Grapefruit. This seemed to have been the motivation behind the National Music Publishers Association awarding her co-songwriter credit at a June 2017 event during which the song was given the Centennial Award. Lennon recalls:

“I know she helped on a lot of the lyrics but I wasn’t man enough to let her have credit… That song was actually written by John and Yoko.”

Again, the inclusion of this information might be divisive for the diehard Beatles fanatic/Ono hater convinced that this woman broke up the band and ruined their favorite mop top, but the passages reproduced from a first edition of Ono’s Grapefruit should dispel any doubts. Get through any prejudice about the people involved, those remaining to tell the tale, and the motivations are pure. Most everything in Imagine John Yoko is white: the piano, a chess set, the light coming in from the window of the room seen through stills of the “Imagine” performance film. Conversely, and refreshingly, neither Lennon (around the time of the song) nor the book shy away from the irony of the song, the cold reality behind the idealism. How could this multimillionaire rock star ask us to “imagine no possessions” while keeping a straight face?

“The reason I got so rich is because I’m so insecure. Yoko doesn’t need it [money]. She always had it. I had to have it. I’m not secure enough to give it all up. I wasn’t content with no dollars, I wasn’t content with a million… contentment doesn’t lie in money.”

Photographers, personal assistants, and secretaries all get their chances to reminisce in Imagine John Yoko. What seems clear now as it probably was for many during that time is that everything about their lives was a performance. Everything was open. The book reproduces a troublesome scene from the documentary, Imagine: John Lennon (Andrew Solt, 1988) in which a clearly troubled man called Claudio comes upon Lennon at his Tittenhurst estate. Lennon engages the troubled Claudio in a discussion about reality. Claudio had been sending Lennon telegrams for nine months: “…I’m coming and then I’ll only have to look in your eyes and I’ll know…” John and Yoko take Claudio in, feed him, and Lennon tries to calm Claudio down:

“…don’t confuse the songs with your own life… I am just a guy, man, who writes songs…”

It’s terrifying in retrospect to consider what could have happened with Claudio, how all that could have ended, and while this book doesn’t address this incident, the fear is there. It’s also hard to reconcile this need John and Yoko felt to document everything in their lives, included what some would see as an exploitation of a troubled young man.

There aren’t as many similar narratives provided here as some readers might like, but it’s enough to understand that giving “vibes” of love and peace would never be a shield against assassination. Instead, Imagine John Yoko goes deep into the album tracks and production details. Lennon notes that it took him nine days to make the album, and the lush sound is amazing.

In a section profiling co-producer Phil Spector, the reader might at first be taken aback. Is this current? Various dates in the references section place it between 2003 and 2007. It’s another interesting irony that such a troubled and violent man like Spector could help produce such beautiful sounds. “I am trying to get my life reasonable,” Spector notes. “I’m not going to ever be happy… it’s very difficult to be reasonable.” Spector doesn’t fully stay on point in this section, but it remains interesting, especially when he recalls that he told a Time reporter trying to compare Lennon with the then recently dead Kurt Cobain: “It’s all been done! It’s all been done!”

The photos are lush throughout Imagine John Yoko, especially shots of George Harrison in action. We see him on dobro and guitar, acting in scenes with Yoko for one of her movies. We read Harrison’s recollections of Lennon as a tough guy, noisy and cheeky. It makes the reader wonder about all the other missed opportunities for collaboration. Longtime Beatle friend Klaus Voorman, who played bass on the album, contributes sketches of Lennon singing, of having to hold the upright bass while drummer Allan White played percussion on the bottom half. The album Imagine does not feature all-killer-no-filler tracks, but the ones that have always worked are effectively recalled: Nicky Hopkins’ emotionally beautiful piano work on “Jealous Guy”, the unapologetic ant-McCartney vindictiveness of “How Do You Sleep”” (featuring a great Harrison slide guitar solo), the softness of “Oh My Love”, King Curtis’s sax on “It’s So Hard”, and “How?”, a song saved by the inherent optimism in its bridge.

Other photos feature John and Yoko chatting up Miles Davis at a random birthday party, various versions of the album cover art, and reproductions of the inner sleeve artwork, which will all be welcome and nostalgic for those of us who bought the LP in the mid-’70s. Reproductions include the poster included in the album package, and the cheeky parody jab at Paul McCartney’s Ram album cover (Apple Music, 1971), where Lennon is holding onto a pig’s ears and staring at the camera like a gentleman farmer. Ono’s album art for her 1970 short film, Fly (shot by Lennon) is still strange and distant after all these years, and the sheer volume of productivity is impressive. The documentary, Imagine, was really less about the songs than an impression of images and improvised sets (no dialogue) featuring Fred Astaire, Harrison, Jack Palance, Dick Cavett, Jonas Mekas, and Andy Warhol. This film and the stories and images behind the making of Ono’s film Fly might frustrate the fan who only wants Lennon stories, but abandoning this book for that reason would be a loss.

Everson Museum Director Jim Harithas recalls the art scene at the time of Ono’s Fall 1971 “This Is Not Here” exhibition:

“In those days, women were marginalized and not expected to be artists. I think we were the first museum to dedicate the whole museum to a woman… the women’s movement was gathering strength in the early Seventies, so it was a really important show… Some of my male colleagues… were really irritated about it.”

It’s an exciting way to end the main section of Imagine John Yoko, before we reflect on the song’s legacy and how (if at all) we might consider its message in these times. In 1984, New York City named a section of Central Park Strawberry Fields, and installed a circular “Imagine” mosaic in its center. It’s a designated “quiet zone”, which accurately reflects the sonic nature of the song. We read of Ono’s work with the organization WhyHunger, and the Imagine Peace Tower in Reykjavik, Iceland. The latter is a beam of light illuminated annually from a remote island location from 9 October (Lennon’s birthday) to 8 December (the anniversary of his death.) It’s illuminated at various other times, and stands as an interesting monument to Lennon’s staying power:

“On a cloudless night, it creates a pillar of light. In rain or snowfall, you can see the beams iridescing with rainbow refractions. When cloudy, it dramatically lights up and reflects off any moving layers of cloud.”

This primary edition of Imagine John Yoko comes in a 9 and ½ X 12 1/8 size, 320 pp., with 1362 illustrations. A Collector’s Edition includes an additional 176 pp. and over 150 new illustrations. A special signed Collector’s edition includes previously unused photographic proofs from the Imagine album cover sessions. As a coffee table book that balances photos with text, the presentation is beautiful and carefully compiled. At least for this reader, Imagine John Yoko is a welcome testimony to this intense moment when two people created such a strong peaceful anthem.

Lennon would temporarily retire from public life in 1975 and resurface in November 1980 to publicize his and Yoko’s comeback album, Double Fantasy (Geffen Records, 1980). He was killed in the midst of the initial publicity push for that album, and at memorials around the world a few days later, “Imagine” was played to the stunned, subdued gathering of mourners. We know what happened to Lennon, so Imagine John Yoko does not need to go through the final part of his story. Instead, this work is about hope, peace and wonder. “It’s a song for children,” Lennon recalls early in this book. “Remember,” Ono writes in her preface, “each one of us has the power to change the world.” Within these sentiments any modern reader should find a place, at least in their minds, where they can feel a sense of home.

* * *

You might also enjoy Thomas Britt’s 2010 interview with Yoko Ono.

- Yoko Ono: Warzone (album review)

- Yoko Ono - "Children Power" (premiere)

- It's Me, I'm Alive: A Conversation with Yoko Ono - PopMatters

- Relisten Without Prejudice to Yoko Ono's 'Plastic Ono Band'

- "I Just Let Things Happen": A Conversation with Yoko Ono

- "Bring on the Lucie": Lennon's Last Overtly Political Stand

- John Lennon and Paul McCartney: The Friendship Heard 'Round

- The Sentimental Journey of John Lennon's "Imagine" - PopMatters