Simon Radowitzky led a remarkable life. Born into working-class poverty in a Jewish family in 1891, his youth was marked by the violent brutality of anti-Semitic pogroms, abortive uprisings and terror attacks against the Tsar. Apprenticed to a locksmith as a boy, he was initiated into the burgeoning workers’ and revolutionary movements, turned anarchist and rapidly became known as a fiery and courageous rebel. Amid worsening repression he fled Russia and immigrated to Argentina, which was filling up with other Russian and Jewish exiles.

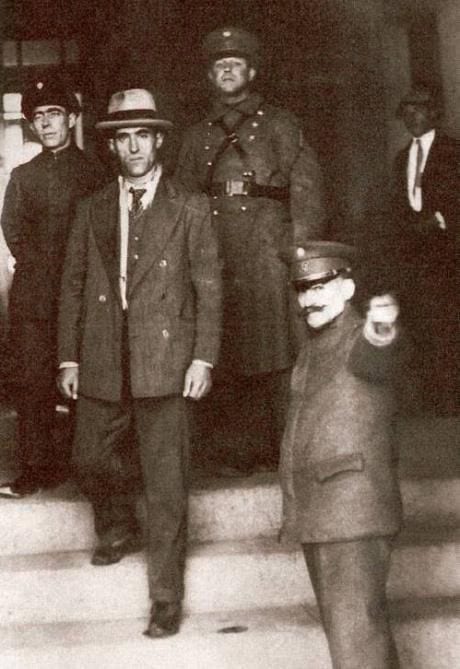

Although still a newcomer, his rebellious anger was roused as he witnessed growing repression in his adopted country as well, in particular terrible state brutality against the labour movement perpetrated by Colonel Falcon, the repressive chief of police who was responsible for the slaughter of a hundred striking workers in 1909. Radowitzky decided he couldn’t stand by and do nothing, and so he assassinated Falcon with a bomb. Sentenced to life in prison at a penal colony (he escaped execution because of his youth – he was barely 18) he became a cause célèbre for workers and radicals throughout South America and beyond.

His brutal treatment in the Argentine prison system was mitigated only slightly by frequent protests and campaigns in his support, which levied growing pressure on the Argentine government. Radowitzky escaped prison, was recaptured, tortured beaten and raped by police, and ultimately released in a broad amnesty from a government reeling under pressure from investigations into prison conditions and desperate for public support. After a brief period in Uruguay (including stints in prison for his part in the movement against that country’s dictator), he moved to Spain when the Civil War broke out in that country, and joined the anarchist forces fighting the fascists there. Upon the Republicans’ defeat by the fascists he managed to escape back across the Atlantic to Mexico, where he died in 1956, a worker in a humble toy factory.

This is the incredible real-life story Spanish comics artist Agustin Comotto was given charge to tell, and his work does this remarkable subject tremendous justice.

The danger with biographical comics is they often attempt to rush through a person’s life, offering little more than narrated history with a visual backdrop. Prisoner 155 avoids that by turning the entire book into a powerful morality tale (with Radowitzky’s early years presented in the form of episodic flashbacks). The bulk of the book centres on Radowitzky’s years in prison, and on his struggle to maintain his dignity and ideals while behind bars and constantly tormented by his police torturers. He maintains a quiet dignity through it all, determining with thoughtful conviction which lines to draw and which battles to pick. Fundamental to this process is that even though he has lost his freedom, he retains a certain degree of autonomy, by deciding when and why to put his very life on the line to preserve his dignity and soul. That’s the difference between enacting ideals in or out of prison: outside, one faces minimal lasting consequences for the everyday choices one makes. Inside, merely making an autonomous choice, in contradiction to the barked orders (or subtle insinuations) of the police inevitably invites beatings and a strong likelihood of death.

Radowitzky became not only a hero for the South American working class (he even had many upper-class fans), but also for his fellow prisoners. Witnessing him maintain his dignity gave them hope and inspiration, and he looked out for these unwilling comrades as well, leveraging the public pressure on prison authorities to improve conditions for them, not merely himself.

There’s a bit of a fantasy play on Comotto’s part that helps Radowitzky retain this inner strength. He clings to the memory of a lost love from his days in Russia, talking to her, retreating to a fantasy-land where she comforts him when the beatings and torture become too intense to bear. It’s a lovely, poignant tale, and but also serves as a reminder that brute defiance alone is insufficient for survival and dignity: ultimately Radowitzky’s resistance is rooted in love.

In today’s politically polarized world, Radowitzky’s tale also taps into an important debate on the use of political violence. He was affiliated with factions of the Russian anarchist movement which espoused violent direct action methods. Indeed, his ultimate act in assassinating a police chief (who was himself responsible for the deaths of dozens of workers) was rooted in this philosophy of direct action and revolutionary violence. Nor did he regret his action; he remained defiantly convinced it was the proper and necessary thing to do in the face of repression. This makes his elevation into a heroic icon by the public all the more interesting. In a way, his decision to fight in the Spanish Civil War was a continuation of that philosophy, for in Spain the anti-fascist forces were already engaged in a broad-based extension of his individual act: taking up arms against tyranny and repression.

The artwork in Prisoner 155 is stunning, and a perfect complement to this profound morality tale. Figures are tastefully pencilled in shades of gray that fittingly renders the long and deeply etched faces of everyone in this sad, heroic tale. The art enables an expressiveness to their facial expressions that complements the narrative perfectly. The dark angularity of the characters; the rough scenic realism refracted in shades of grey and black (interspersed only with red in those rough and bloody prison sequences and other scenes involving violence); all combines terrifically to convey the stark, deeply chiseled idealism of the protagonists.

Prisoner 155 is a worthy telling of the life of a remarkable man. It’s a tale which deserves to be remembered and told, and the tremendous literary and artistic quality of the book places it in a category with other heroic tales of resistance and perseverance in pursuit of an ideal (Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela comes to mind, if only because of the similarly grueling years of imprisonment and solitary confinement, and the mental discipline required to survive it). Unlike Mandela, Radowitzky did not emerge from prison to inherit the national leadership of a country. But his story, retold through the talented pen of Agustin Comotto, now survives to inspire future generations of rebels.